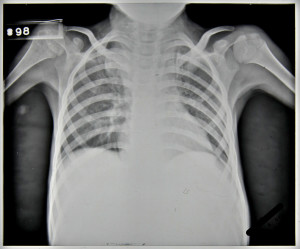

Patient 81/39, a five year old boy, was admitted to Stannington in December 1937 due to ailing health following a two month period in bed suffering from mumps. He had developed a cough, was easily tired and was losing weight. The initial x-ray reports detail a blocked apex in the left lung and marked mottling in the right lung leading to an initial diagnosis of Pulmonary TB, Figure 1. However, following his admission further symptoms started to manifest themselves which indicated that the diagnosis of this patient was more complex than it was initially considered to be.

In April 1938, it was noted the patient had two subcutaneous abscesses on the iliac crest and the knee. A sample of the mucus taken from the abscess on the hip was sent for bacteriological examination. Results of this testing were as follows:

‘scanty pus cells and much granular debris. No definite organisms seen and tubercle bacilli not found.’

Furthermore, periostitis was noted in the upper end of the ulna which ‘appears septic’ but was regarded as being non-tuberculous. The patient still suffered with a cough but sputum tests were negative and notes state that no tuberculosis was seen. At this stage the x-ray report indicates that no bone lesions are seen in either the leg or the iliac crest, Figures 2 and 3.

Throughout the rest of 1938, the patient’s condition is very variable. An additional abscess is noted in the lumbar region with slight discharge and the apex of the left lung becomes more blocked with the lower lobe of the right lung being described as having been ‘studded with deposits’, however, the sinuses in the thigh and gluteus region are healed.

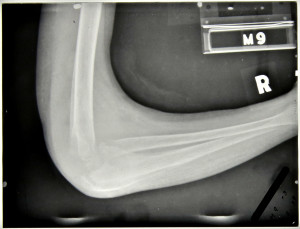

The main focus of the notes centre upon the right elbow which, in September 1938, was described as being very active with discharging abscesses; periostitis was greatly increased in the ulna and also present in the humerus with the joint being ‘badly involved’, see Figure 4. In November 1938 large sequestrum was removed from the elbow, at this time all lesions were considered very active. The elbow continued to be active with an increasing number of ulcers noted to have appeared; a maximum of four seen in February 1939 including one in the right cubital fossa which is incised to produce ‘copious…pus’, Figure 5.

X-ray reports from September 1939 read as follows:

11/9/39 – Ulna hollowed out to cavity

Radius dislocated upward & forward

Lower end humerus eroded & partly destroyed.

15/9/39 – Ulna – upper end partially destroyed, disorganisation of elbow joint’

No further comment is made regarding a diagnosis of tuberculosis in the elbow.

In addition to ongoing changes in the elbow an abscess appeared on the right mastoid, which was opened and drained in October 1938 and is noted to have become less active by November 1938. However, this abscess continued to open throughout the patient’s stay at Stannington and is often referred to as ‘discharging freely,’ with a diminishment in its activeness finally being noted in October 1939.

Further skeletal changes are observed in the x-ray report notes from September 1939, Figures 6 and 7:

11/9/39 – Leg – large cavity in fibula L and in head of R. tibia

15/9/39 – Left fibula large focus

Right tibia large focus passing through into epiphysis.

Combined with this the medical notes indicate that a sinus developed on the left ankle and another on the right tibia during the same period with a further sinus developing in November 1939.

This patient was transferred from Stannington in February 1940 to a local hospital in West Hartlepool, his home town, as showing No Medical Improvement and a final diagnosis of TB Bones and Joints and old lung lesion. His final x-ray report, see Figures 8-12, dated 27th February 1940, reads:

‘Large cavity head of R.tibia & sequestrum seem smaller than 11/9/39

Elbow –Improved

Fibula – large cavity little change.

Skull – little seen

Chest – L.apex clearer much mottling’

The multifocal nature of this patient coupled with comments throughout the notes on possible non-TB origin is suggestive of a potential differential diagnosis. Any further comments based upon the information provided and radiographic images would be welcomed.

Sounds like it could be osteomyelitis, which is typically caused by a bacterial infection (staph). “Young children primarily experience acute hematogenous osteomyelitis due to the rich vascular supply in their growing bones” (Kalyoussef,, S et al. updated Feb 12, 214 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/967095-overview#a0104). The same source states it is more common in males and pre-school aged children.

There seems to be a zone of consolidation in the left lung apex, and diffuse mottling throughout most of the right lung. Progressively there is periosteal reaction on the distal right humerus, with increasing resorptive destruction of the trochlea. Radiologically there is loss of the proximal ulna,,but this seems to be postoperative ? excision of sequestrum. There is increasing periosteal reaction on the proximal ulna with soft tissue swelling. Fig 9 shows extensive destruction of the distal end of the humerus and proximal ulna.

There is a large lytic lesion in the proximal metaphysis of the Left tibia, penetrating the epiphyseal cartilage into the epiphysis, and penetration of the medial and lateral cortical bone. There is perilesional sclerosis around these lesions.

There is an expansive elliptical cavitation of the distal left fibula with a large cortical defect, perilesional sclerosis and involucrum and sequestrum.

If these progressive chronic lesions are of infective ?tuberculous or pyogenic aetiology, it is puzzling that there have not been any bacteriological findings. If the lesions are tuberculous, then the quite marked perilesional sclerosis is perhaps unusual in such a young patient. I think that the chronic nature and multi site involvement and lung lesions precludes a diagnosis of pyogenic osteomyelitis.

Notwithstanding these comments, my primary diagnosis is tuberculosis. But I suggest that Sarcoidosis may be a differential diagnosis. Unlikely in view of the multiple osseous lesions, but the tibial lesion may also support a diagnosis of fibrous cortical defect.

Keith Manchester. BARC, University of Bradford