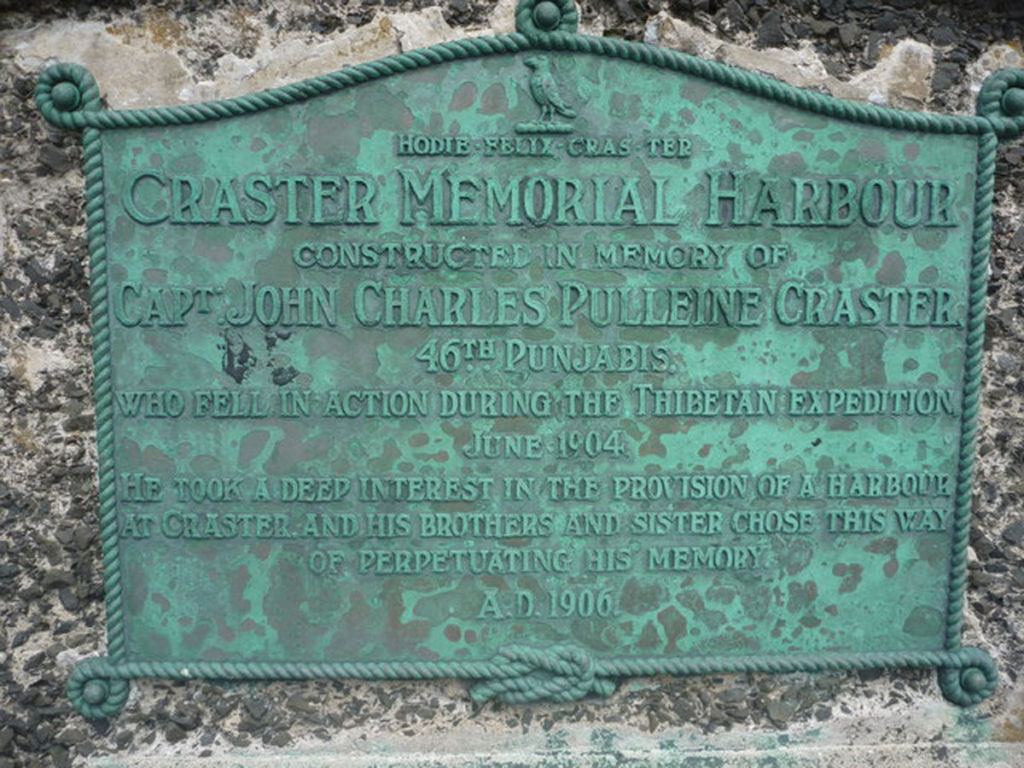

Craster is small village on the Northumberland Coast, famed for its kippers and with a long heritage of fishing. At first glance it would appear to have little connection to country of Tibet. But on closer inspection of the Harbour, a plaque reveals that there is a connection.

By George Robinson, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13678994

The Crasters have lived in the area since the 11th Century and built the Tower that bears their name and it was there that John Craster lived after his birth in 1871. His father, also John, had been born in Ireland and his wife Charlotte in Scotland. As well as John they had five other children Thomas [born 1860]; Amy [1862]; Edmund [1863]; William [1867]; and Walter [1874].

John joined the Northumberland Fusiliers and was appointed 2nd Lieutenant in 1892, being promoted to Lieutenant in 1899 and finally Captain in 1901. He had joined the Indian Army staff in 1895 and throughout the later part of the 1890s took part in campaigns all along the Northwest Frontier. By 1903 he was an Adjutant, the rank he held when he volunteered for the expedition to Tibet.

The reasons for the trade mission to Tibet, which became effectively an invasion, are obscure. But it is argued that the British Government was concerned about potential Russian influence in the area. Rumours were circulating that the Chinese Government, which ruled Tibet, were intending to allow the province to be taken over by Russia. This would have allowed the Russians a direct overland route to India, the jewel in Britain’s imperial crown. Credence had been lent to these rumours by a Russian exploration mission to Tibet, which had taken the first photographs of Lhasa some four years earlier. Tensions between Britain and Russia were high due to the recent conclusion of what was known as ‘The Great Game’, a struggle between the two powers for control of territories in Central and Southern Asia.

Whatever the reasons, the expedition pushed into the interior, inciting a response. Despite the Tibetan forces best efforts, they were grossly outgunned and their flintlock muskets were no match for Maxim Guns. They had particular trouble firing down onto British Forces as their muskets lacked sufficient wadding, causing the musket ball to simply role out of the weapon when at an angle. Most of the Tibetan Muskets were also Matchlock, using a simple lit taper to ignite the powder, a process that became virtually impossible in the rain. It’s estimated that 2000-3000 Tibetans were killed while the British lost some 200. Of one engagement, Lieutenant Arthur Hadow, commander of the Maxim guns detachment, wrote “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire, though the general’s order was to make as big a bag as possible. I hope I shall never again have to shoot down men walking away.”

It was during fighting at Tsechen, that John Craster was killed. Tsechen consisted of a village, overlooked by a monastery and fortress. Gurkhas stormed the monastery, defended by some 1200 monks mostly armed with rocks, while Craster’s regiment cleared the town. The fighting was all but done, with a only small band in one house giving any resistance. The British forces suffered only two casualties, one of which was John Craster, who was shot through the head at almost point blank range by a musket.

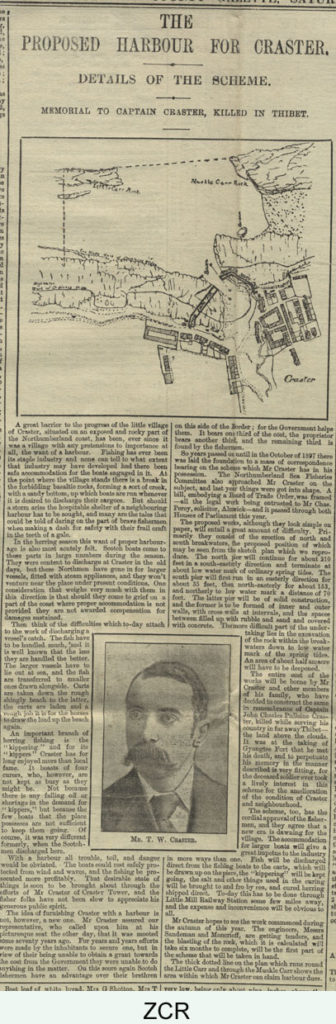

After his death it soon became apparent that Captain Craster had no Will and that his military service and travelling meant he had assets scattered throughout the British Empire. The task of administering these assets must have been considerable. However, once it was done his estate proved considerable and it was decided to use some of it to fund the building of Harbour, something that had Captain Craster had been a keen advocate of.

Plans were drawn up by Mr J Watt Sandeman of Newcastle and the legal and parliamentary issues were dealt with by Charles Percy & Son, Solicitors of Alnwick. Formal Application to the Board of Trade for a provisional order was made in Autumn 1904 and this received Parliamentary sanction in 1905. The work excavating the rock on the site of the Harbour began in October of that year, and in July 1906 the first concrete for the piers was put in place. The North Pier was completed in September 1907 with work commencing on the South pier the following December.

It was originally intended to be a smaller Harbour than was eventually built, but extra money was obtained from the Fishery Board for Scotland and from the Treasury. The excavation was out of solid basalt and much of the work had to be done at low tide, which might account for the delay in completion of the South Pier. The Harbour was finally completed in 1910.