BERWICK ADVERTISER, 15 DECEMBER 1916

WAR NEWS

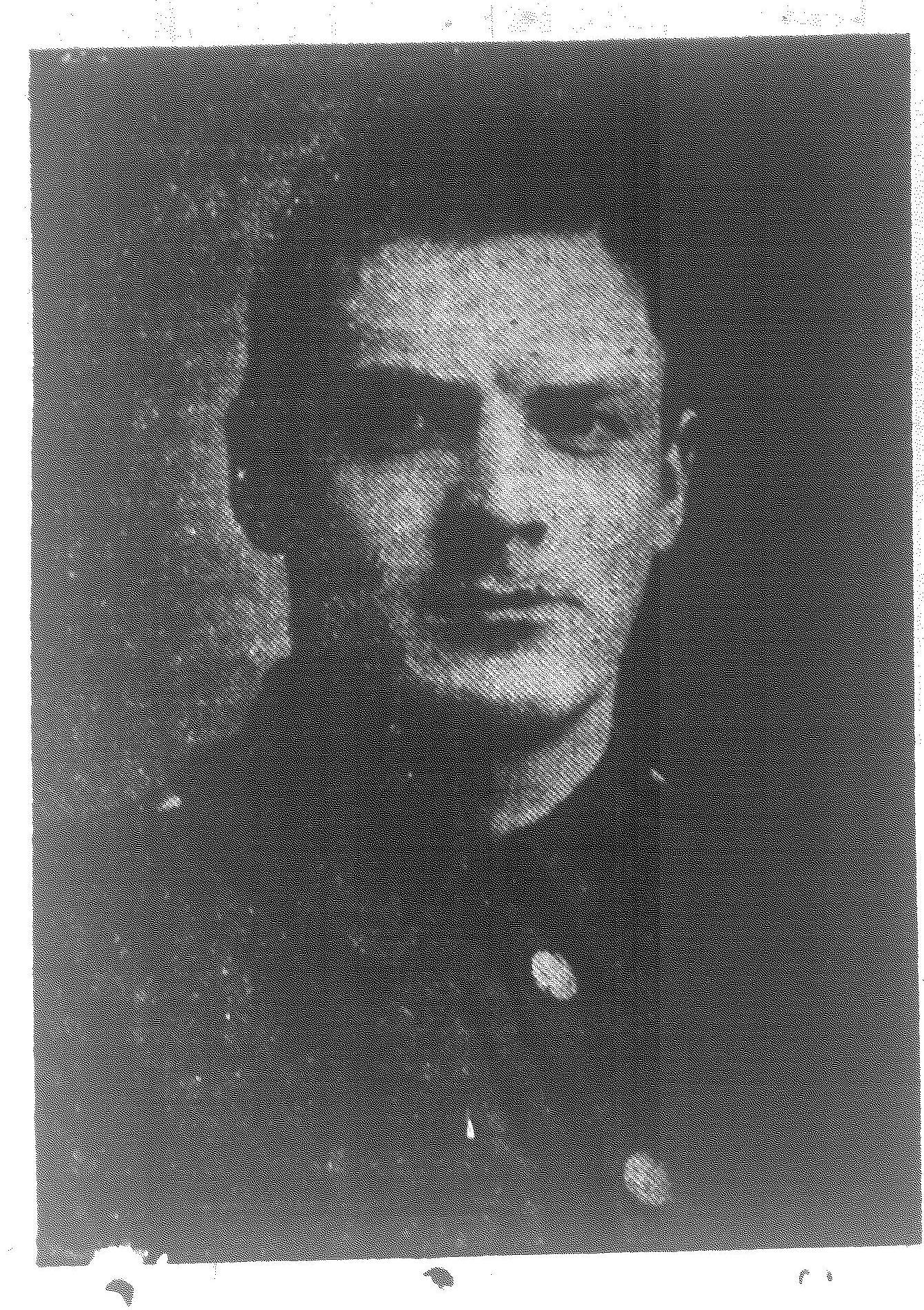

PROMISING CAREER ENDED

BERWICK MILITARY MEDALIST KILLED

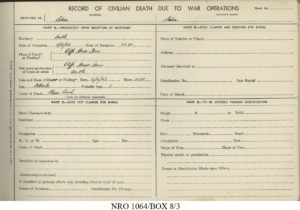

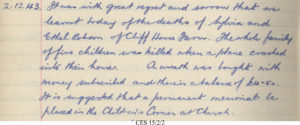

It is with deep regret that we announce today the death of Corpl. J. E. Boal, N.F, only sonof Mr Thos. Boal, West Street, killed in action in France while engaged at the Trench Mortar School, behind the lines. The deceased lad was at the opening of a brilliant career when war cast its pall over the homes of Europe. Every honour which the Berwick Grammar School could offer, be it scholastic or athletic, he secured by ability which was recognised by all in the school, which has lost one more from its glorious roll of honour. Only so recently as October it was a pleasure to us to record the wining of the Military Medal by this gallant lad, and the fact that he had accepted a commission and was expected to arrive home at any time, has bought a deeper sadness with his untimely death. Corpl. Boal was a student at Skerry’s College, Newcastle, when war broke out, and he immediately left his studies and enlisted. His record of army service has been as excellent as when at school, and with the sorrowing father and family in this over whelming loss we are sure all most deeply sympathise.

The following is the letter received this morning:-

Trench Mortar Battery

9th December

Dear Mr Boal,

It is with the very deepest regret that I write to tell you of your son’s death. He was killed today, at a Trench Mortar School behind the lines, together with two of my officers, and six men of the battery. I was wounded myself and have not yet got over the shock that the loss of such grand men gave me, so I trust you will excuse this very short and disjointed letter. I only trust that you will be given strength to hear this terrible blow, and I hope if consolation is possible at such a time that you may derive a little from knowing that your son is buried in a village cemetery, and that his grave will be under the care of the good French people of the village. I will write you again in a few days, when I have had time to recover from this terrible blow, but please write me if there is anything you wish me to do. With my heart-felt sympathy.

I am

Yours sincerely,

L.S. Thomson, Capt.

LOCAL NEWS

Farm Labour in Berwick District. – In view of the recent hiring fairs, the Board of Agriculture for Scotland have obtained specially full reports on the subject of labour. In the Lothians skilled labour is unobtainable, and in Berwick, Roxburgh, and Selkirk, where little regular hiring is done at this season, great difficulty has been found in filling vacancies. The wages of foremen in Fife are reckoned at £75 per annum, including perquisites, while in the Lothians ploughmen get 30s a week, with allowances, and women 20s.

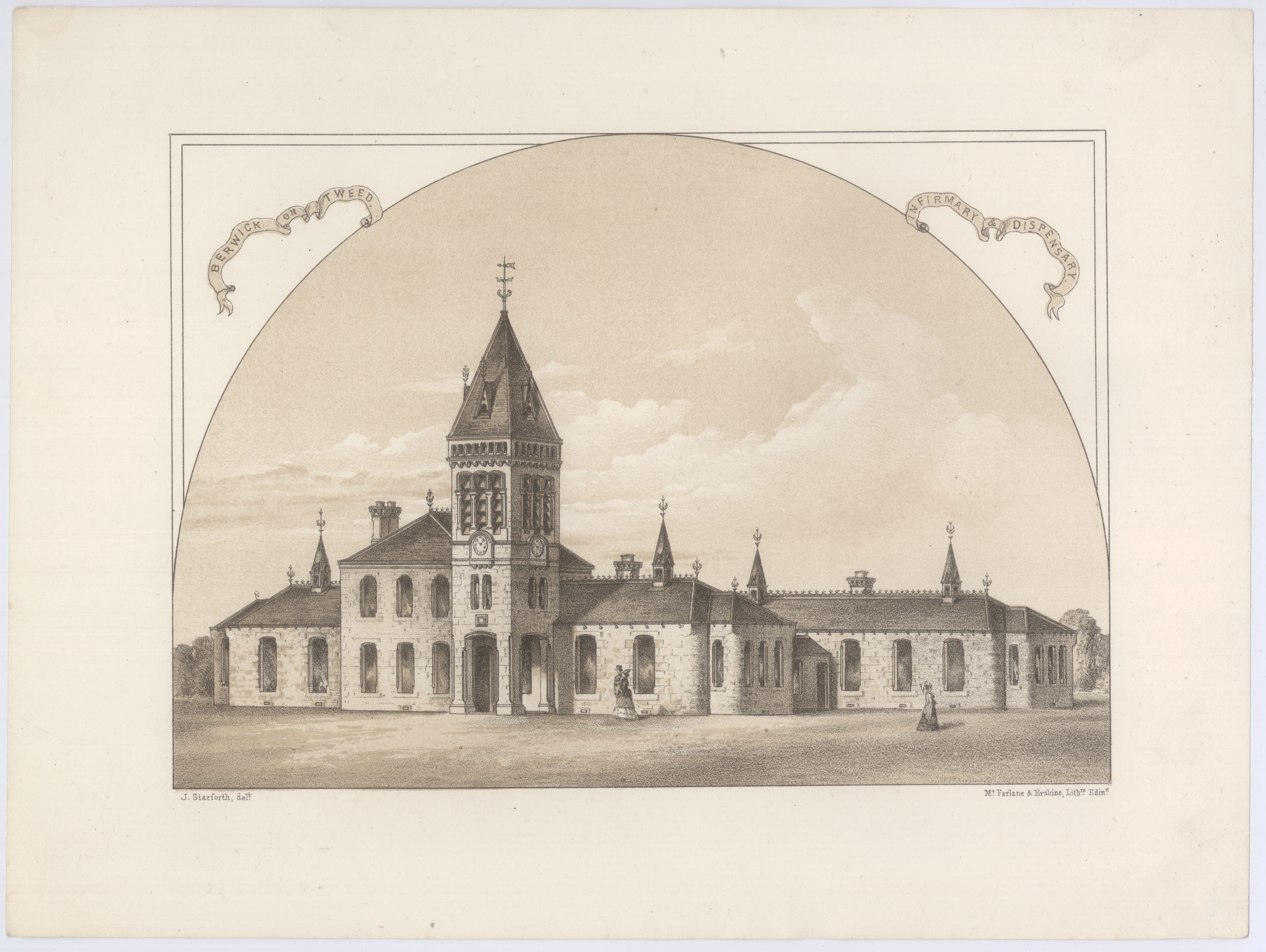

Fatal Burning Accident. – About 12.30pm on Tuesday an unusual and fatal burning accident occurred at 61 Castlegate, Berwick. Mrs Thompson, wife of James Thompson, Army Ordinance Corps, stationed in England, went into a neighbour’s house on an errand, leaving her child, Blanc Rena Alice Thompson, nine months, sitting in a chair on a rug in front of the fire. When she returned a few minutes later she discovered the child’s clothing and night dress to be on fire, which she immediately extinguished. It was found that the infant had been burned on the legs and lower part of the body, and it was speedily removed to the Infirmary, where it was attended to by Dr Maclagan. Despite all that could be done for it the little sufferer died on Wednesday. It is supposed that the child’s clothing was ignited by a spark from the fire.

Belford and District News

BELFORD

On Sunday evening last a memorial service was held in the Presbyterian Church, Belford, in memory of the young soldier Private W. Anderson, who has given his life for his country. The minister, the Rev. J. Miller, preached a most impressive sermon from Psalms 46, verses 1-6, the subject being entitled “The Song of Faith in the Season of Sorrow.” Private Howard of the Northern Cyclists sang very feelingly “O Dry Those Tears.” The Church was crowded.

Disquieting News. – news was received by someone in the district about the beginning of last week that Private William Anderson, son of Mr and Mrs Anderson, of Easington Grange, Belford, had died in a hospital in France from wounds received in battle. At the time of writing the parents of the brave young lad have had no definite information from any source, but we regret to say they are inclined to believe the rumour will be correct.

SEAHOUSES

George Clark Relief Fund. – The Hon. Treasurer has received a further sum of ten shillings to this fund from Mr Wm. Chisam, Yetlington. Mr Chisam, who recently lost a son in France, says – “I have, unfortunately, no one in the trenches to send a Christmas parcel to now, so George is welcome to the “mite” that would probably have gone elsewhere under other circumstances.” He adds very truly, – “Our damaged fighting men should not have to depend on charity, they have a right to due support, and I hope the new Government will get it.