Thomas Creevey was born in Liverpool in 1768, allegedly the son of William Creevey, a Liverpool merchant, he is believed by some to have been the illegitimate son of Charles William, 1st Earl of Sefton. After graduating from Queens College, Cambridge in 1789 he was called to the bar in 1794. In 1802 he married Eleanor Ord, the Widow of William Ord a Northumberland Landowner and M.P. for Newcastle, and daughter of Charles Brandling of Gosforth. Eleanor was also a distant cousin of Charles Grey and a friend of the Prince of Wales. A socially and politically advantageous match, it was no coincidence that in the year of his marriage, Creevey also became M.P. for Thetford.

Creevey was a Whig and a follower of Charles James Fox. In 1806, when the brief “All the Talents” ministry was formed, he was given the office of secretary to the Board of Control. In 1830, when next his party came into power, Creevey, who had lost his seat in Parliament, was appointed treasurer of the ordnance; and subsequently Lord Melbourne made him treasurer of Greenwich Hospital (1834).

Although he had a distinguished political career, Creevey is better remembered for the time he spent away from Britain. In 1814 he and his then very unwell wife, left England for Brussels where they were to spend the next five years. It was during this time that Creevey was to come to know the Duke of Wellington, and to have the distinction of being the first civilian to interview him after the Battle of Waterloo. It was during that interview that Wellington made his famous assessment of the battle “It has been a damned nice thing. The nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.”

Creevey had intended to write a history of the times he lived in, and apparently to that end collected and saved his own voluminous correspondence. He was a man of some considerable charm and this along with his intellect, meant many of the leading political figures of the day valued his company. As such he was afforded an uncommon degree of intimacy with them. His wife died in 1818 leaving Creevey with very scant means of his own. However, his popularity meant that his friends often looked after him although it was noted by Charles Cavendish Fulke Greville in 1829 “old Creevey is a living proof that a man may be perfectly happy and exceedingly poor. I think he is the only man I know in society who possesses nothing.”

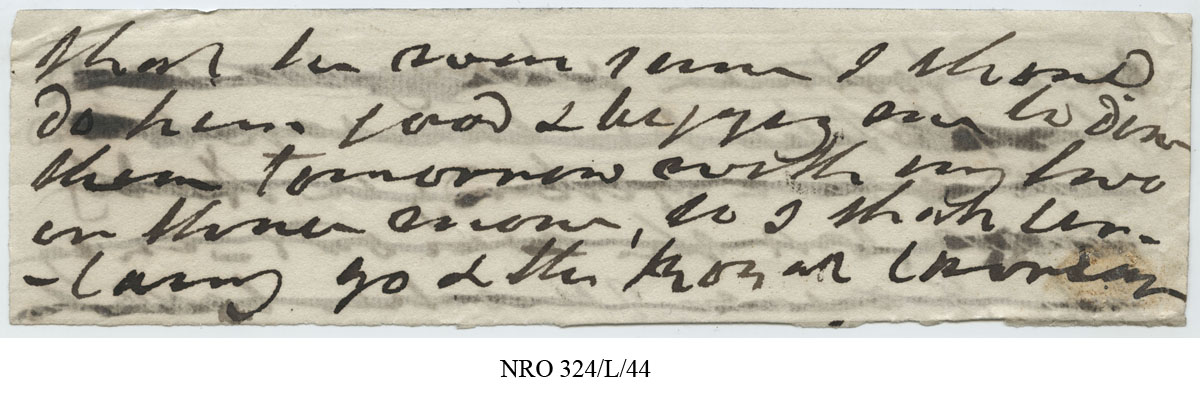

Creevey died in 1838 and was largely forgotten to history. His papers were consigned to the attic of Whitfield Hall in Northumberland, after having passed to his stepdaughter Elizabeth Ord. As well as his correspondence, the papers include his journals, many were faithfully kept by Elizabeth, indeed she saw fit to transcribe many of them in her own hand. An act that has been much praised by those who have studied Creevey’s papers who describe his own writing, without exception, as “simply execrable”. However, Creevey is also known to have kept a copious diary covering 36 years of his life, but it was apparently destroyed sometime after his death by friends fearing exposure of the contents.

A chance enquiry during a tour of the house in 1900 led to the publication of ‘The Creevey Papers’. These two volumes captured the late Georgian era with sparkling political and social gossip and an almost Pepysian outspokenness, and they took London by storm. No one described more graphically the appearance, or recorded more faithfully the looks and the talk, of the royal personages and major politicians of the time. Not least among his humorous touches is the extensive use of nicknames for many of the major personages of the day, “Prinney” for George IV; “Beelzebub” for Henry Brougham; “Madagascar” for Lady Holland and “the beau” for the Duke of Wellington. Others include “Og of Bashan” “King Jog” “King Tom” “Niffy Naffy” “Slice” “Snip” and “Clunch,”.

The Creevey Papers are held by Northumberland Archives as part of the Blackett-Ord Family of Whitfield Collection. Due to its large size there is a huge amount of material not included in the original ‘The Creevey Papers’ publication, or its subsequent iterations. It’s likely that further exploration of the material could yield even more from this extraordinary record of a man’s life through a turbulent time in history.