This guest blog has been written by Professor Annie Tindley from Newcastle University.

‘Messers Atkinson and Marshall the first adventurers in stock farming in the earldom of Sutherland are stock and crop farmers, who reside near the river Aln in Northumberland. They breed and buy lean stock which they feed for Morpeth and the Yorkshire markets; and with the last 10 years they have embarked … not less than £20,000 on putting breeding flocks in the mountains of Sutherland …

I could not keep contemplating with wonder the boldness of that spirit of adventure which had led men, living quietly in that fine county to overleap all (one would think) to the unfathomable mountains and ravines betwixt the Aln and the Shin …

It has established on the great scale cheviot sheep and cheviot shepherds and connected Sutherland in the most intimate manner with the joint stock community, the kingdom …’1

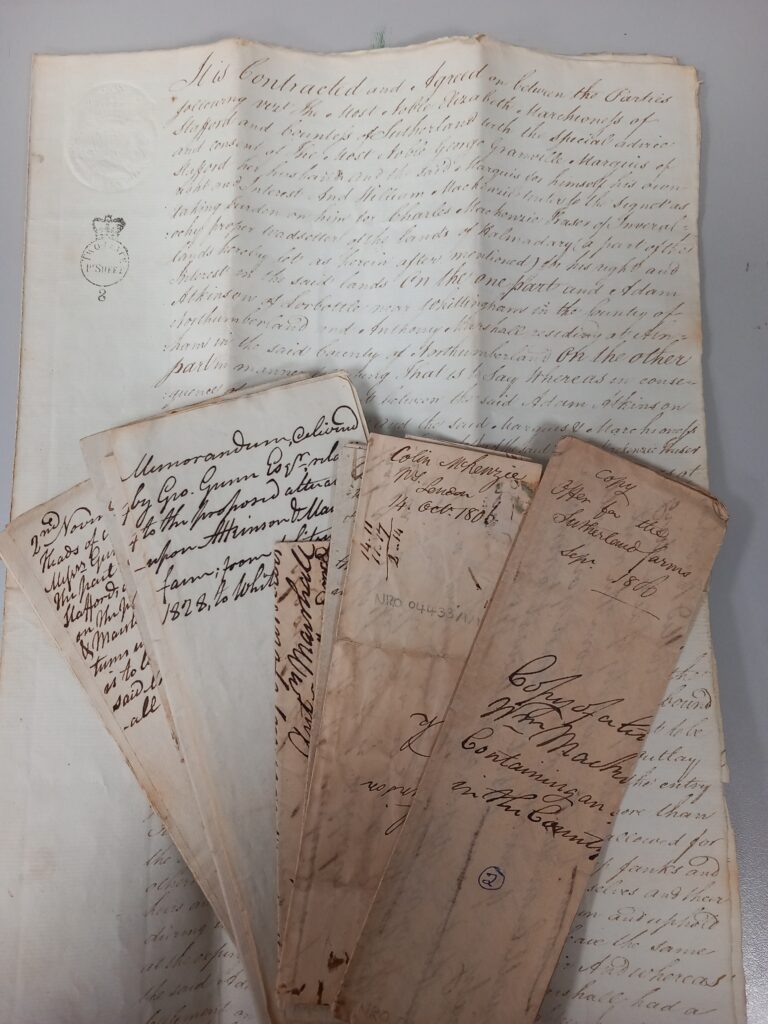

So wrote Patrick Sellar in around 1820, thirteen years after Stephen Atkinson and Anthony Marshall, two sheep farmers (and brothers-in-law) working in partnership in Northumberland, invested in the pioneer sheep farming county of Sutherland in the far north of Scotland. They had made a further enormous commercial success from what was without doubt a risky venture on their part: Sutherland was still seen as relatively beyond the pale, a highly peripheral region in Britain’s burgeoning industrial and imperial economy. They had established themselves raising the new cheviot sheep breed in Northumberland, principally for wool, which they sold via Yorkshire brokers to the newly expanding textile mills in that county. They had also successfully developed a new workforce of skilled shepherds, well rewarded men who managed flocks of sheep thousands strong.

In 1807, they took up new leases of sheep walks on offer from the Sutherland Estate, one of Britain’s largest landed estates, owned by the earls and dukes of Sutherland. The Sutherland Estate was in the throes of a revolution of its tenancy and economic structure, moving away from the trade in black cattle and subsistence agriculture to a more commercial model based around sheep, which – as the Improving minds of the period had it – could be raised in the harsh environment there.

This revolution is known to us as the Sutherland Clearances, a part of the wider Highland Clearances, which saw the Introduction of wholescale commercial sheep farming across the region. In Sutherland between 1806 and 1821 it led to the removal or eviction of around 15,000 people from the straths and glens to the coasts to make room for the new sheep walks. Atkinson and Marshall were among a new cadre of tenants of these enormous sheep walks, which ran into the tens of thousands of acres. This was part of the attraction for them: to scale-up their already successful enterprises and utilise the skilled workforce they had developed. The downside was that the rents they had to pay were also enormous: their farm at Clebrig for example came at a cost of £1500 per annum.2

What becomes very clear from this unique archival collection is what a high risk, high capital game the early days of commercial sheep farming was: huge sums were required for stocking the new farms and paying the large rents charged. Huge profits were also possible, as Atkinson and Marshall demonstrated. They had to fight for those profits, however, and they were not shy about making significant demands on their new landlords. We can see this in the sometimes acrimonious negotiations between Atkinson and Marshall and the Sutherland Estate management over terms and conditions and the rents themselves: sheep products were part of an unstable global market, subject to rapid spikes and drops. This meant watching every detail down to the smallest loss: in the early years of sheep farming one of the key threats was loss of sheep through natural causes such as the weather, but also against sheep stealing by local populations. Atkinson and Marshall pressed the Estate hard to pay for additional protection of their flock, threatening to take legal action if this was not forthcoming:

‘As I believe the safety of their flocks was one of the first considerations that weighed with the tacksmen [tenants] at taking the Sutherland farms … their protection expressly stipulated for by them in their offer, they certainly think themselves entitled to demand that protection … For unless such protection had been promised the tacksmen would never have embarked in the enterprise at all.’3

Despite being one of the largest and most powerful estates in the country, they had to meet the demands of their new tenants to justify the enormous expense and upheaval already undertaken to introduce sheep farming.

Neither Atkinson or Marshall ever lived in Sutherland on their sheep farms: they ran the operations from afar, mainly through correspondence and their cadre of skilled shepherds. The rewards were great, however; the Atkinsons built Lorbottle Hall near Rothbury from their proceeds and funded the imperial careers of their descendants until well into the twentieth century, becoming part of the gentry class. What is very clear from this collection is the sheer scale of the national and global networks – of people, ideas and goods (wool in this case) – that underpinned and connected the Agricultural Revolution in disparate parts of the country, fuelled by growing global and imperial markets and staffed by hardheaded, effective men pushing forward in the risky business of the new commercial sheep farming.

The author would like to acknowledge with thanks the generous funding of the Strathmartine Trust, which made this work possible.

Images

Lorbottle Hall (Wikipedia commons)

Dunrobin Castle (Wikipedia commons

1 Northumberland Archives, Atkinson and Marshall, Patrick Sellar to James Loch, NRO 04433/1/2/93, n.d. [1820]. Patrick Sellar was the notorious sheep farming tenant and agent for the Sutherland Estate from the early nineteenth century, and James Loch the Commissioner for the Estate, his overseer.

2 Northumberland Archives, Atkinson and Marshall, NRO 04433/1/1/4, James Loch to Messers Atkinson and Marshall, 21 Sept. 1822.

3 Northumberland Archives, Atkinson and Marshall, NRO 04433/1/2/55, Marshall to William Mackenzie [the Sutherland Estate’s lawyer], 4 Sept. 1809.