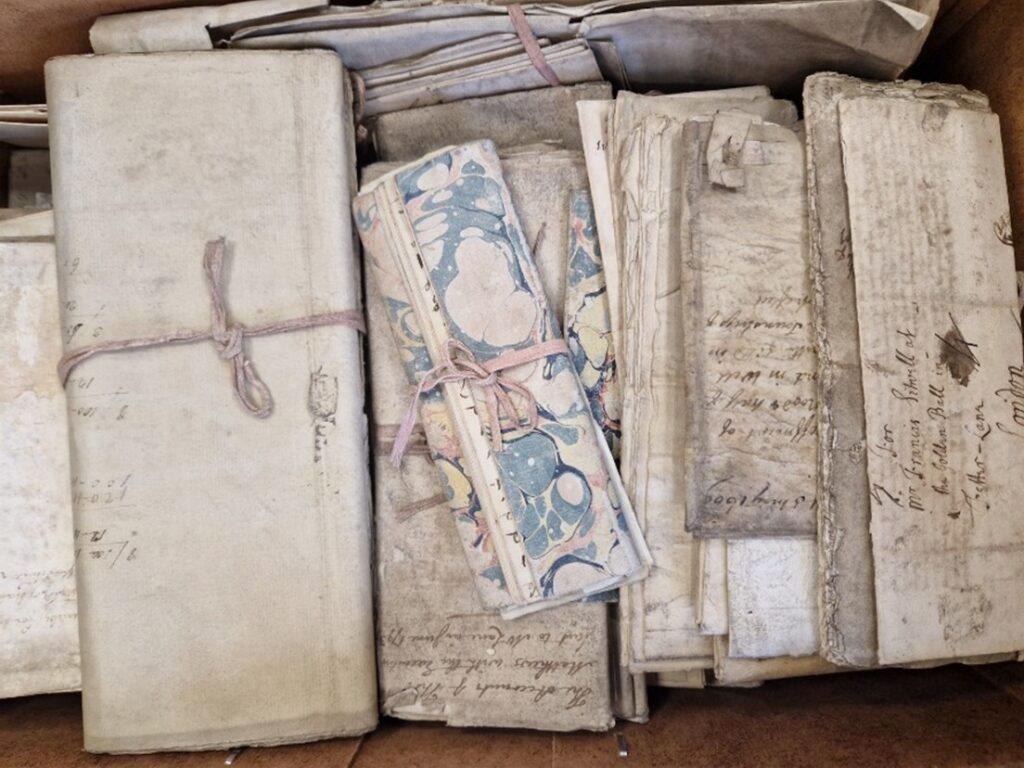

Recently, I worked on a project to catalogue an estate collection for the Phipp’s family (NRO 2372). The collection mostly relates to Samuel Phipps, largely compiling of accounts detailing his expenditure in life, and further accounts and inventories of his properties following his death in 1791. The majority of these records relate to his lands in Northumberland, with Phipps owning the Barmoor estate during his lifetime, but there are records for his lands in Yorkshire, Derbyshire and London. In my previous blog, I included the following image of correspondence, noting that these sorts of records can tell us a lot about the families concerned.

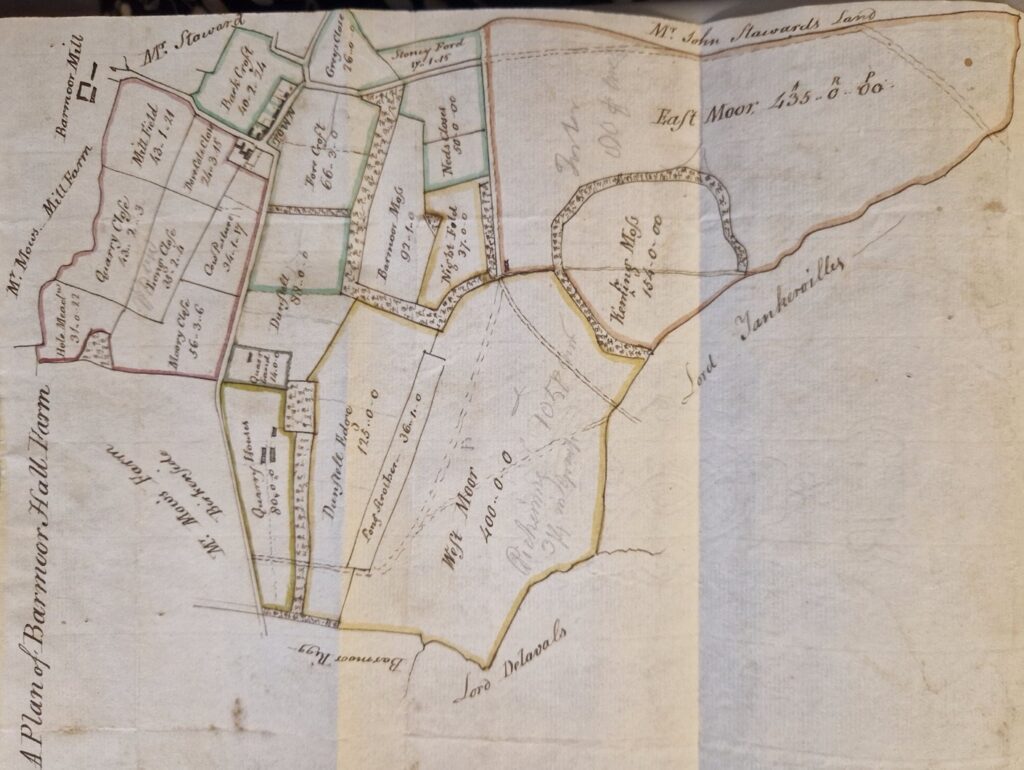

A closer look will tell you that there are detailed accounts of Phipps’ expenditures, both within his estate and annuity payments to relatives. Many of these relatives are members of the Sitwell family, alluding to the family connection – Phipp’s second cousin, Francis Sitwell, was his heir. The outputs are extensive, implying Samuel Phipps was quite a wealthy man. We do have some evidence of attempts to reduce expenditure though. Many of the documents in this collection which were written during Samuel Phipp’s lifetime, relate to his attempts to sell or lease his land in Northumberland. He even employs two well-known agricultural surveyors of the day, George Culley and John Bailey to survey his land. Culley and Bailey were known for their 1794 publication ‘A General View of The Agriculture of The County of Northumberland with Observations on the Means of Its Improvement.’ This level of investigation is useful for us as it means that we have maps and plans of the Barmoor estate within this collection. This allows us to see exactly what was included in Phipps’ estates, and better understand the boundaries.

In one set of correspondence, Bailey writes to Phipps with regards to his attempt to lease ‘Barmoor Hall Farm’. He states that in attempting to locate someone to rent the farm as one property, he is receiving offers which are far below the value of the lands. The asking price was £600 per annum for 21 years, and their last offer, for example was for £500 for the first 10 years, and £600 for the final 11 years of the lease. Bailey has then attempted to advertise the land in three farms, instead of one, but this somewhat backfired, in that the original interested party rescinded his offer for the whole, and requested only one of the parts, again for less than asked. If you look at the plan below, which was enclosed with Bailey’s letter, the sections that he refers to seem to be the West Moor, East Moor and Kenning(?) Moss. Bailey even pencilled in the interested parties.

When asking other potential farmers why they would not bid for the property, Bailey states that they all replied similarly: “There was so much bad land, and the harvest so late, that they could not think about it”. Bailey argues that there is 300 acres of good land, and 1300 acres of bad, but that the price is set accordingly. Bailey then goes on to detail the lease agreements for the other sections of the farm. Unfortunately, the issue of whether the advertised lands were leased is not resolved in this letter, though this short 4 pages of correspondence, is certainly packed full of useful information. From this, we can see exactly what lands were included in the farm, who the neighbouring landowners were, the value of the leases, and we’ve learnt that there was a consensus at the time (though contested!) that much of the Barmoor land was struggling to yield crops.

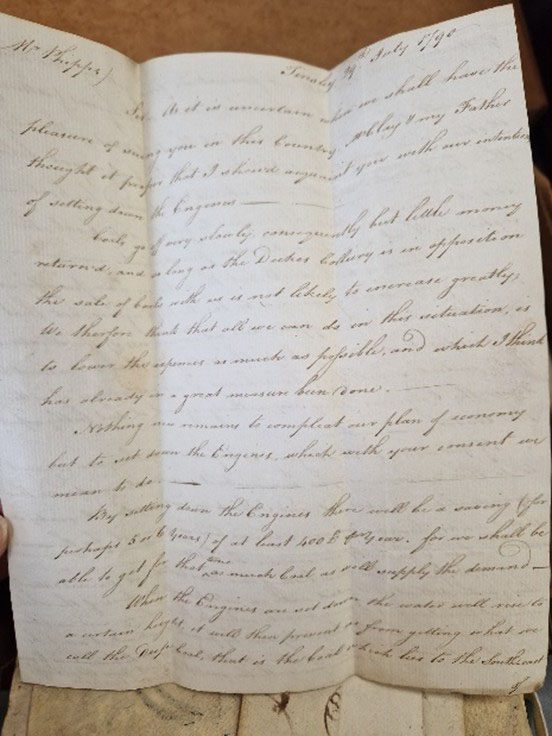

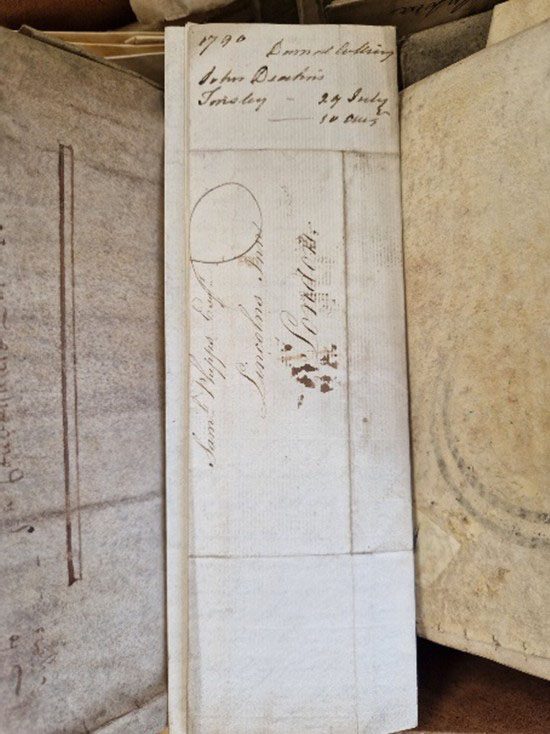

In one letter sent from John Bratins at Darnall Colliery (Yorkshire), we find Bratins strongly suggesting that the ‘machines’ should be ‘shut off’ to save on costings. The ‘machines’ referred to here were used to remove accumulated water from the coal fields, allowing access to the lower levels of coal. Bratins states that without access to this level, they will still be able to collect enough coal to cover both their own ‘in-house’ needs and their supply demands, so use of the machines is a costly and unnecessary expense. He renders competition from the Duke’s neighbouring colliery as the reason for their lack of demand, and mentions that the Duke is aware of the suggestion to turn off the machines, and has not objected, despite this meaning that the water will likely travel to his fields. The move to turn off these machines does suggest an attempt to reduce expenditure.

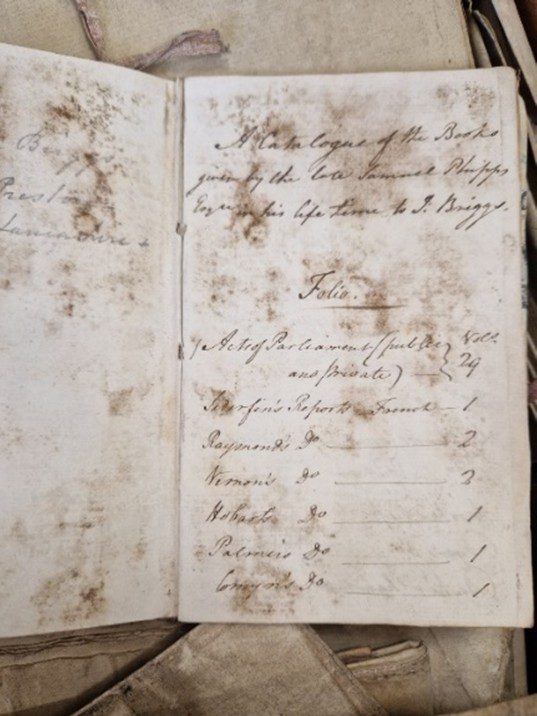

We also have some fascinating indications of Samuel Phipps daily life in this collection, in the inventories from his properties. Many of the inventories were taken following Phipps’ death and would have been used to identify the inheritance owed to his heirs. Inventories were written for each of his properties, and in this collection include contents of rooms, which can give us a good idea of the type of property Phipps was living in, and the furniture which adorned his living quarters. From a general interest viewpoint, this can tell us a lot about life in the late eighteenth century – what furniture was fashionable, for example. My personal favourite inventories though are the lists of books held by Phipps at his various properties. Each of the books are named, and a value assigned to them. They include novels, non-fiction books and publications, and provide a real insight into the sorts of books which could be found in a personal collection at the time. Of course, these books may have merely been purchased as an investment, though the number of publications does, at least to me, suggest a man who had an interest in reading. In the image below, you can see a list of books which were offered to a J. Briggs, during Phipps’ lifetime. There is a nice letter at the end of the book, which confirms that this promise was made, and that his executors ensured Briggs received the books.

These are just some observations from the Phipps collection and hopefully provide a hint of the sorts of information to be found in the collection. Keep an eye on this blog for future findings, I’m sure that there will be some interesting finds ahead!

Beth Elliott, Project Archivist.