Andrew Buglass arrived at the Royal Naval Barracks, Portsmouth, in mid-February 1916. From his first letter home, we learn that Andrew hates the Navy and wishes to return home and from there, join the army – as his brother George had done. The weather does not help his mood. Neither does the inconsiderate treatment he says he receives from his superiors and the doctor. On Monday 7th February Andrew writes,

‘I was seeing the doctor this morning & had a lot of lip, said there was nothing the matter with me when I told him my state of mind, and said I was starting badly & said I had better look out or there would be trouble which made me worse than ever, but he gave me some more medicine for my stomach.’

Andrew wrote two letters on 15th February; one to his father and one to his mother. The letter to his mother is cheerful, stating he is in the Soldiers and Sailors Rest drinking the cocoa which she had sent him. The letter to his father is much darker, and continues the tone from his previous letters. He states that ‘…today has been the worst day I have spent yet’, and that he is even thinking of deserting. By the 17th February 1916, Andrew is in the Sick Bay. He seems to be increasingly unwell, thinking he may have influenza. The letter also illustrates Andrew’s fragile mental state. He writes,

‘…I dread the coming of the night with its sweats and hideous dreams. I sometimes wish I was dead anything is better than this…’

Ordinary Seaman Andrew Buglass died of pneumonia on 28th February 1916, little more than a month into his training. He was 22 years old. He was buried in Cambo Holy Trinity churchyard and is also commemorated on the Rutherford College War Memorial tablet, along with 151 men who were his Masters and fellow pupils.

Lance Corporal George Anderson Buglass enlisted on 16th October 1915 at Newcastle upon Tyne, and joined the Kings Royal Rifle Corps, 21st Battalion, designated the ‘Yeoman Rifles’. This battalion was formed from farming communities in Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland (hence Yeoman).

Training and equipping began after arrival at Aldershot in September 1915. On 26th April 1916 the Division was inspected by H.M. The King, who was accompanied by Field Marshall Lord French and General Sir A. Hunter. Entrainment began on May Day 1916 and by 8th May, the Division had completed its concentration between Hazebrouck and Bailleul, France. Within the collection we have some of the letters George wrote home from the trenches to members of his family. In one letter, written to his mother, Lizzie, he talks about watching gunfire over the trenches.

‘We sometimes see the flash of the guns after dark and last night at dusk we saw them bombarding an aeroplane but it must have been a long way off as we could only see the flashes but could not hear the sound of the explosion.’

In one of his final letters before going over the top, dated 13th September 1916, and addressed to his father, George makes quite a prophetic statement,

‘…We are going up to the trenches soon and as it is a rather hot corner some of us will be getting “blighties”.’

George and his comrades in the 21st Battalion were involved in the front line, in a support role, at Delville Wood in July 1916. Their first involvement as an attack formation was in that part of the Somme battle known as the Battle of Flers-Coucelette, 15th-22nd September, which saw the very first use of tanks in battle. George would have been one of the first to view these tanks, as the first one to advance started from the north end of Delville Wood, close to his position. At Zero Hour, George and his friends left Edge Trench and advanced across No Man’s Land, towards their first objective, which was secured by 07:00 hours. The advance continued to the second objective, the western end of Flers Trench, immediately south of the village of Flers. There was further fighting here, but the allotted section of trench was taken by the 21st Division after 30 minutes or so. There was a delay which caused the advance to the third objective not to take place until mid-afternoon. After this, there were no more advances this day. As the troops were consolidating their gains, the German counter-barrage began. In the evening, there were German attacks which were repulsed, but the shellfire continued. George would have been under machine gun fire as well as German counter attacks.

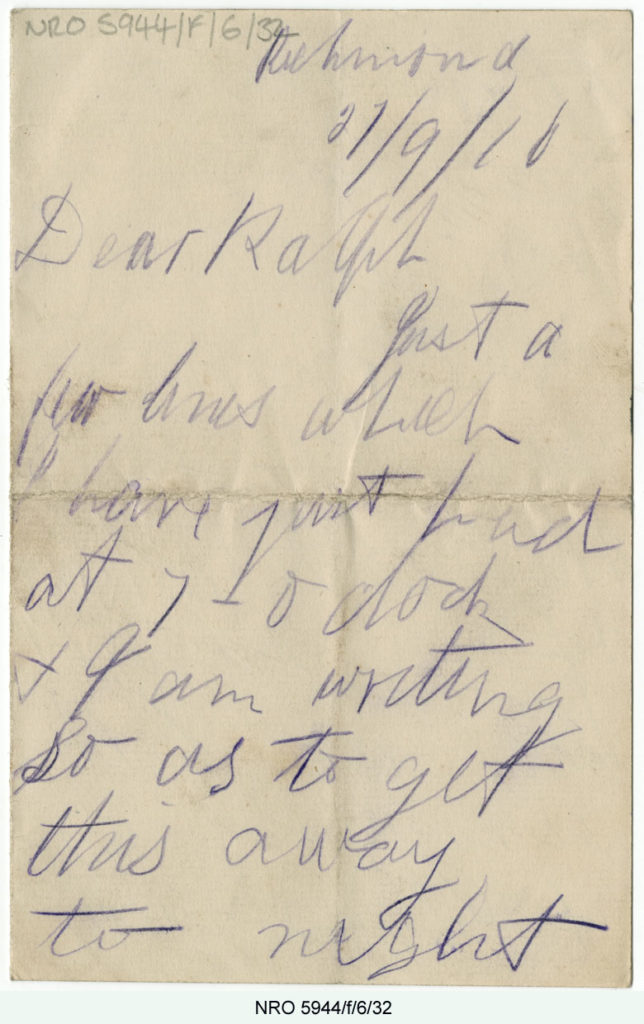

It seems likely that George was wounded sometime on the 15th, corresponding with his service records, which list that George was wounded, probably by shrapnel, in his neck, right arm, and buttock. The wet, muddy conditions would have made his, and many others’, recovery very difficult. George would probably have been taken first to the Regimental Aid Post which would be in, or very close to, the front line. From there he would have gone to a Main Dressing Station. He was taken to a Casualty Clearing Station on 16th September, and then on to No. 3 Stationary Hospital at Rouen on the 18th. On the 19th September he arrived at Richmond Military Hospital, London.

George’s health seemed to improve whilst at Richmond, and he received some visitors, including his father. George wrote some letters home whilst in hospital and the childish handwriting is evidence of the wounds he received in his right arm. Yet, on 6th October, he died, somewhat unexpectedly. His service records list that he died of ‘haemoptysis’ – the coughing up of blood/blood-stained sputum from the lungs, which is a sign of tuberculosis, respiratory infections, and pneumonia.