This guest blog was written by Alison Johnson

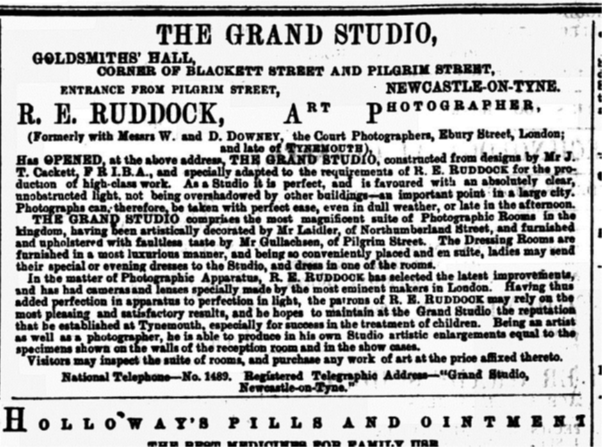

Thousands of people walk past the Northern Goldsmiths building in the centre of Newcastle on Tyne every day and never look up at the north facing windows, where, in the late 19th Century, the light was just right for an artist. It was in these rooms in 1892 that Richard Emerson Ruddock, artist photographer, opened his Grand Studio.

Richard had already been working as a photographer at 20 Front Street, Tynemouth, in partnership with Matthew Anty, after learning his trade with W & D Downey in London. The brothers Downey had started out as photographers in the Market Place, South Shields but moved to Newcastle and then to London, at the invitation of a local MP Mr Ingram, and become Court Photographer to Queen Victoria.

The Grand Studio had the most fashionable furniture and décor to impress Richard’s clients, provided by Gullachsen’s, located next door to the Goldsmiths Hall, and the most modern photographic equipment from London and from Hurman Ltd, who owned a photographic warehouse at St Nicholas Building, Newcastle.

The Shields Daily News of 8 September 1892 described the grace and elegance of the rooms in the Grand Studio in extensive detail. The photography took place on the upper floor, with a well-lighted camera room furnished with Axminster rugs and upholstered chairs, and two work rooms. The main floor below held two dressing rooms, with the one facing Pilgrim Street, designed for the use of lady visitors, furnished in Italian walnut with a large wardrobe, a dressing table and a cheval glass so that the sitter could see a full view of her clothing. The main reception room, 40 feet by 25 feet, was also on this floor, with a white ceiling, pale lemon walls and white woodwork. Here there were more luxurious rugs, comfortable seating and a piano. An article in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle of 28 March 1894, describes a meeting in this room with Blondin, the Hero of Niagara and the tight-rope, who had come to the Grand Studio to have his portrait taken. There was also a room for the secretarial part of the business on this floor.

Geraldine, the fashion and household columnist of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, visited the Grand Studio in October 1892 and wrote “What I like about this profession is that gentlemen and their wives can work together. Mrs Lydell Sawyer, Mrs Robert Barrass, and Mrs Ruddock each holds a place in their respective reception rooms. This is, perhaps, a trifle awkward sometimes, since visitors seem to think the ladies cannot do for them what they require. Ladies and gentlemen call and desire to see the photographer himself: and when their business has been ascertained, it is discovered that the lady in attendance could have done quite as well as the photographer could.”

It appears that Richard was aiming to photograph the famous, the great and the good of Newcastle and the surrounding area. One of his first portraits at his new studio was of Mr W Sutton, the Mayor of Newcastle, who formally opened the new studio. He also took photographs, which were converted into illustrations by engraving, for both local and national newspapers, such as for an article about a billiards championship.

These also included photographs of ordinary people such as Mrs Allison, the young wife of a miner living in Windy Nook, Gateshead. An article in the Jarrow Express, 1 September 1899, described her illness and her remarkable recovery which she attributed to Dr William’s pink pills.

Few of Richard’s photographs survive from the many that he must have taken, going by reports in local newspapers. There are three in the National Portrait Gallery, London. He took photographs of some of the Presidents of the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers; these hang in the Lecture Theatre at Neville Hall in Newcastle, now the home of The Common Room. Durham University has copies of the book Ushaw College: A Centenary Memorial, with many illustrations from a series of photographs taken by Richard. The Ushaw Library holds the original photographs. Northumberland Archives also holds a copy of the booklet Grand Photographic Views of Cramlington and District (NRO 00482/10, views taken by Richard.

Richard’s brother, John Candlish Ruddock (1866-1933), had a photographic business in Alnwick. Some of his photographs are also held by the Northumberland Archives.

It seems that Richard suffered from the modern problem of unauthorised use of his photographs, because he took the trouble to have several of them patented; the surviving patents, with copies of the photographs, are held in the National Archives in London.

Why did Richard decide to set up his Grand Studio rather than staying in Tynemouth? It’s clear from the description of the studio that he was ambitious, but Richard was already well connected to the Newcastle area when he opened the Grand Studio. His father was the Richard Ruddock who was the managing editor of the Newcastle Chronicle newspaper from 1878 to 1908. One of his younger sisters, Bertha, married the grandson of William Wailes, the famous stained-glass manufacturer, who built Saltwell Towers in Gateshead.

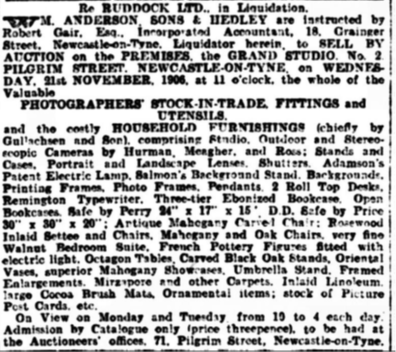

For some years it appears that his photography business was successful, but in 1906 a notice appeared in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle of 19 November 1906 that told of the end of the Grand Studio. The notice gave details of the photographic equipment and the furnishings that were to be auctioned, including the very fine Walnut bedroom suite described at the opening of the Grand Studio.

Newcastle Daily Chronicle 19 November 1906

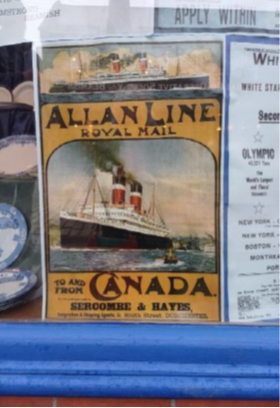

It seems that the writing was on the wall about the failure of the business and his financial difficulties long before the notice of sale appeared. The Newcastle Weekly Chronicle of 24 September 1892 mentioned five well established and three new professional photographers that had set up business in Newcastle and said of the Grand Studio “It is in truth a gorgeous affair, the new studio in the new building sat at the corner of Blackett Street. To sustain the weight of the costly and elaborate outfit Mr Ruddock will need to do an enormous business.” And in May 1906 his eldest son, Richard Fenwick Ruddock, emigrated to Canada on board the Virginian, operated by the Allan Line. He took advantage of a cheap assisted passage from Liverpool to Montreal by going as a labourer; this might be an indication of financial problems in the Ruddock family.

Poster in the printer’s shop, 1900s Town, Beamish Museum

At some point between 1906 and 1911, Richard, his wife, his two other sons and his daughter, moved to Bristol. In the 1911 census, he gave his occupation as a photographer on his own account. It appears that his business did not prosper in Bristol because in April 1914 he emigrated to Canada and from there to Seattle in the USA, leaving his family behind.

The First World War brought yet more difficulties for Richard and his wife. Two sons were killed fighting in WW1 and Eugene, his youngest son was wounded in the hip.

Richard Fenwick Ruddock, their eldest son, enlisted in the Canadian Engineers and then transferred to the Infantry Brigade of the Northumberland Fusiliers as an intelligence officer with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. He was sniped during the morning of 18 June 1916 and was buried in the Kemmel Chateau Military Cemetery, Belgium.

Richard Emerson Ruddock’s wife Alice, and their daughter Emmeline, age 15, emigrated to Canada and then, on 13 July 1916, entered the USA from British Columbia to join him in Seattle.

Eugene Ruddock emigrated to Seattle in November 1917 via Canada, paid for by himself. His American draft card of 1917 gave his military experience as two years a Private in the infantry, shot in the hip.

Reginald Barnett Ruddock, their second son, was killed on 6 April 1918. He had joined the Northumberland Fusiliers but was attached to the Bedfordshire Regiment as 2nd Lt/Acting Captain when he died at Mesnil. He is commemorated on the Pozieres memorial in France.

In the 1920 Census what remained of the Ruddock family was living at Y, King and Seattle City, Washington State. Richard was working as a photographer.

Richard Emerson Ruddock died in Seattle in 1931.

(To view details of photographs by Richard Emmerson Ruddock and his brother John Candish Ruddock held by Northumberland Archives, enter Ruddock photo* on our online catalogue https://calmview.northumberland.gov.uk/)