This guest blog has been written by Philippa Day.

I recently completed my MSc in Genealogical, Paleographic and Heraldic Studies at the University of Strathclyde. My dissertation focused on children who were admitted to Northumberland County Mental Hospital between 1900-1918. As my research had a genealogical focus, I was interested in investigating what these records could tell us about the children’s family backgrounds, reasons for their admittance and what happened to them. I was particularly interested in whether any evidence of family mental illness was documented in records and whether different diagnoses led to different consequences for the children. I also wanted to explore the usefulness of these records as a genealogical source.

Background

The 1845 Lunacy and County Asylums Acts required all counties and boroughs in England and Wales to provide suitable accommodation for their pauper lunatics.2 Northumberland County Pauper Lunatic Asylum opened on 16 March 1859 and throughout the years it had several name changes; in 1890 it became Northumberland County Mental Hospital and in 1937 it was renamed St. George’s Hospital.

There are many studies of asylums, although few have focused specifically on children. This is partially because there were never high numbers of children in asylums; most were cared for at home or were incarcerated in workhouses. Increasing legislation in the second half of the nineteenth century also resulted in many children being sent to specialist institutions. This continued into the early twentieth century, with the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act and the 1914 Elementary Education (Defective and Epileptic Children) Act further identifying children defined as ‘mentally defective.’ There was also a requirement that Local Education Boards informed the newly formed Board of Control of all ‘idiot’ and ‘imbecile’ children, as well as providing specialist support for other ‘mentally deficient’ children, with the ability to segregate them for life.3,4 Idiocy was defined as having an IQ of less than 25, or a mental age of less than 3 and imbecility defined as an IQ of between 26 and 50, with a mental age of less than 6.5 Although this terminology is now considered out-dated and unacceptable, these were medical definitions which were accepted at the time.

Asylum records

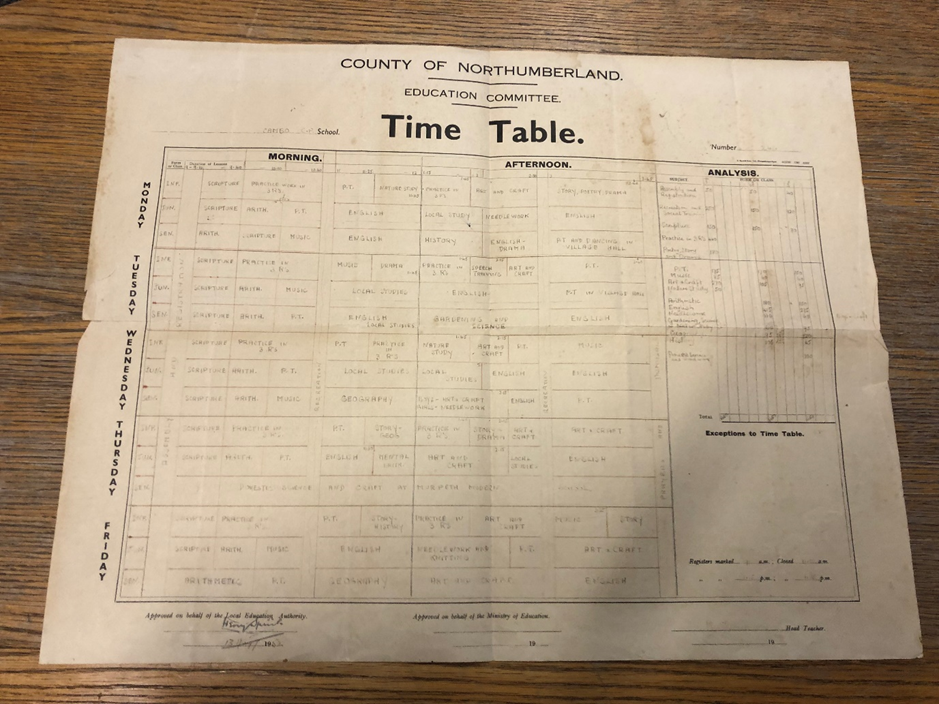

Northumberland Archives hold a large body of records from Northumberland County Lunatic Asylum, which are all rich in information. Initially, to identify how many children had been admitted to the asylum during this period, I used Registers of Patients from 1900-1906 and Civil Registers of Patients from 1907-1918. Medical Registers were also used to extract additional information. There were 113 entries for children between 1900-1918, some of these included children who were re-admitted, so in total there were 102 individual children admitted during this time.

Once the children had been identified through the registers, I searched case books to locate the children’s case notes. Children appeared in the same books as adults, so in total there were thirty-two male case books and twenty-eight female case books to look through. These records contained detailed information including reasons for their admittance, family background, medical treatment and their life in the asylum. For those children who stayed much longer, their notes were transferred to chronic case books. The 1890 Lunacy Act required the disclosure of ‘insane’ relatives on a patient’s admission records and this information was included for some children, as well as supposed causes of insanity.6

Relative Address Books were also valuable in identifying a child’s next of kin and Registers of Removals, Discharges, Transfers and Deaths also helped to ascertain what happened to the child. I also used traditional genealogical sources such as Ancestry to fill in gaps or corroborate information.

Children’s background

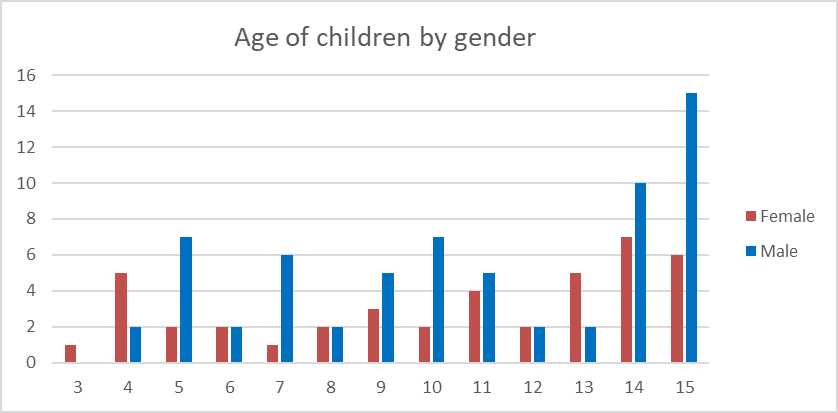

Sixty-nine boys and forty-four girls were admitted to the asylum between 1900-1918, with a greater proportion of older children being admitted, with boys outnumbering girls. However, there were some very young children admitted; seventeen were either aged 5 or under, the youngest being only 3 years old.

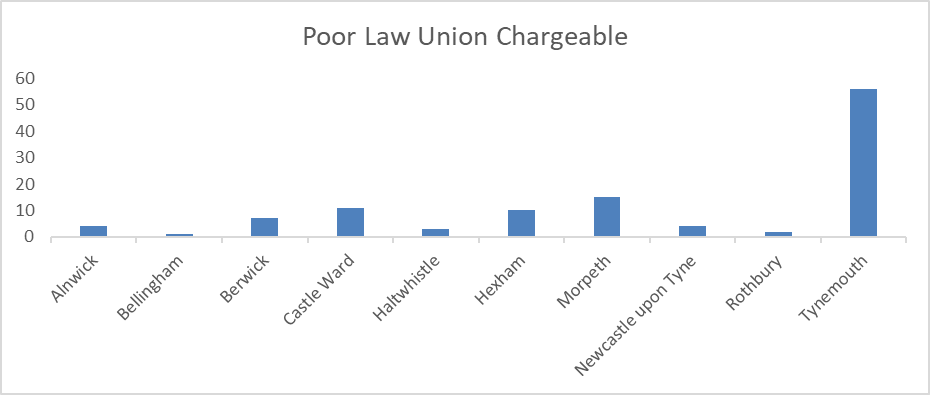

Children were admitted from ten Poor Law Unions across Northumberland, with just under half coming from Tynemouth Poor Law Union. Thirty of the children were admitted from workhouses, thirteen of them coming from Tynemouth Workhouse, eight of which were diagnosed with ‘idiocy.’ Case notes from these children indicate they were becoming difficult to manage in the workhouse, some of the boys were described as mischievous or dangerous, or irritating to other inmates. The girls’ case notes indicated they were noisy or required constant supervision.

Reasons for admittance

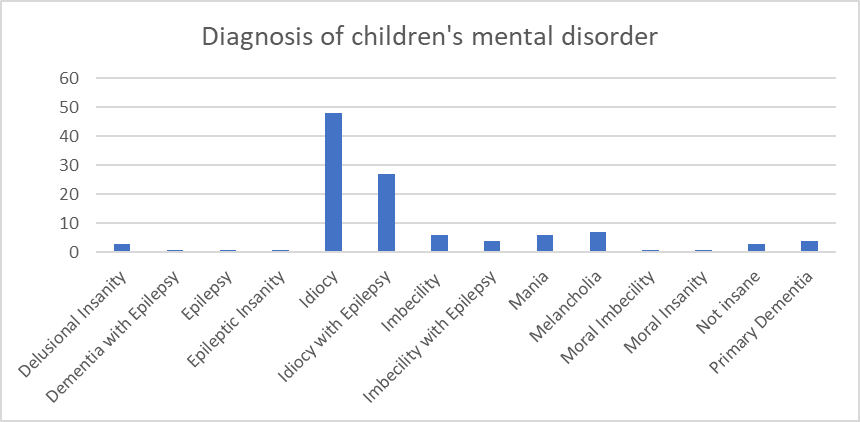

Most of the children admitted had learning difficulties, whilst only a small number had been diagnosed with a mental illness. Seventy-five children were either diagnosed as ‘idiots,’ or ‘idiots with epilepsy,’ and ten were diagnosed as ‘imbeciles, ‘or ‘imbeciles with epilepsy.’ However, it was evident from the case book notes that those children classed as ‘idiots,’ had a mix of complex additional needs, including sensory impairments and physical disabilities. Several children were admitted with existing illnesses and at least nine had congenital syphilis. Thirty-four children were recorded as having epilepsy as part of their initial diagnosis, although some were diagnosed after they were admitted. Sixteen of these children were described as dangerous or not to be trusted, including Arthur, who was admitted on 3 April 1901, when he was 15, diagnosed with imbecility with epilepsy. Arthur was evidently a character, as upon admission he kept making faces and winking when his photo was being taken. Arthur’s case notes suggest that actually he was a gentle character; he loved reciting poetry and enjoyed looking at his picture books. Often parents desperate for help would exaggerate claims that their child was dangerous or violent, to gain access to medical support in the asylum. 7

Amongst the children admitted were two sets of siblings. Mary, who was discussed in a previous blog by Northumberland Archives in August 2022, was admitted with her brother, William, on the 15 April 1903 from their home in Hexham, both diagnosed with idiocy. Mary was 4 and William 7. Their father commented on both his children’s inability to speak, as well as William’s refusal to eat food, Mary being ‘very restless,’ having a ‘vacant look.’ Medical examinations found the children ‘poorly nourished.’ Their notes state that their mother died of decline, whilst William’s states that his father was ‘not very temperate.’

Further research into the children from the 1901 census found that they were living with their parents as well as their grandmother in Hexham. 8 It was a requirement that any person with an ‘infirmity’ was identified on census records, but neither child is identified as such. Following the deaths of their mother and grandmother, it seemed likely that their father was struggling to cope on his own with two young, disabled children. William died in the asylum from phthisis pulmonalis on 12 April 1915 aged 19. Mary was discharged relieved on 4 April 1925 and in 1939 lived at 69A Newgate Street, Morpeth, which was a workhouse. 9,10 Mary died in 1966 aged 66. 11

[2] Burtinshaw, Kathryn & Burt, John. (2017) Lunatics, Imbeciles and Idiots: A History of Insanity in Nineteenth-Century Britain and Ireland. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Limited. p.38.

[3] Cruickshank, Marjorie. (1976) Mary Dendy, 1855‐1933, Pioneer of Residential Schools for the Feeble Minded. Journal of Educational Administration and History. 8 (1). Routledge. p. 28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022062760080105 : accessed 7 May 2023.

[4] Jackson, Mark. (1996) Institutional Provision for the feeble-minded in Edwardian England: Sandlebridge and the scientific morality of permanent care. In: Wright, David and Digby, Anne., eds. From Idiocy to Mental Deficiency: Historical perspectives on people with learning disabilities. London: Routledge. p.168.

[5] Burtinshaw & Burt (2017) op. cit. p.240.

[6] Melling, Joseph, Adair, Richard, and Forsythe, Bill. (1997) “A Proper Lunatic for Two Years”: Pauper Lunatic Children in Victorian and Edwardian England. Child Admissions to the Devon County Asylum, 1845–1914. Journal of Social History. 31 (2). pp. 377. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/31.2.371 : accessed 30 January 2023.

[7] Taylor, Steven J. (2016) Depraved, Deprived, Dangerous and Deviant: Depicting the Insane Child in England’s County Asylums, 1845–1907. History. 101 4 (347). Wiley. pp. 521-529. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26624557 : accessed 18 October 2022.

[8] Census records. England. Hexham, Northumberland. 31 March 1901. SWINBURNE, Thomas (head). PN 4824. FL 67. ED 13. SN 77. p.13. http://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 1 June 2023.

[9] 1939 Register. England. Morpeth, Northumberland. SWINBURNE, Mary. 29 September 1939. Schedule 64. RG 101/2983a. National Archives (Great Britain), Kew, England. Collection: 1939 England and Wales Register. http://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 2 June 2023.

[10] Higginbotham, Peter. (2023) The Workhouse in Morpeth, Northumberland. https://workhouses.org.uk/Morpeth/ : accessed 14 June 2023.

[11] Deaths index (CR) England & Wales. RD Northumberland Central, Northumberland. 3rd Q., 1966. SWINBURNE, Mary. Vol. 1b. p.249. http://www.gro.co.uk : accessed 2 June 2023