Eugene Sullivan was born in Bangalore, India in around 1833. His parents were British subjects, and his birth place suggests that his father may have held either military or governmental positions in the ever-expanding British Empire. Eugene appears to have continued the colonial legacy of his parents by joining the British army at the age of 18. His active military career lasted eighteen years before he requested to be discharged in 1870. During the discharge process a Manchester-based military hearing was given a synopsis of his career. The hearing was told that Sullivan had spent over twelve years of his military career stationed abroad. Through piecing together Eugene’s war record it would appear he witnessed both the Crimean War (in 1853) and the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (also known as the Indian Mutiny or The Great Rebellion). Eugene’s military postings had taken him to the farthest frontiers of the British Empire – often into dangerous and politically dubious areas. Greater detail of his posts were given as follows; three and a half years in the East Indies, just under five years in the West Indies, seven months in the Mediterranean, a year in Crimea and five years in Canada.

During one of his postings abroad Eugene married his English-born wife Emma Parsons. They were joined together on the 4th March 1857 within an Anglican Garrison in Canada. Together the couple had a total of eight children over a twenty-four year period, with Emma and the three eldest children having followed Eugene across the world.

Their eldest child, Hannah E, was born soon after their marriage in 1858. Following her birth the family moved to Bermuda for a short period, where William J was born in 1861. They then returned to Canada and in 1868 Eugene D was born. Eugene the younger would grow up to become a reverend with a keen eye for financial sales and shares, whilst William would become a skilled workman crafting cabinets. Both brothers would subsequently die in the same death year: 1923.

Following Eugene’s request to be discharged from the army the Sullivan’s settled in Northumberland. A third son, Ernest Lewis, was born soon after their return to England in 1871. He was baptised at St Paul’s church in Alnwick, near the family’s lodgings at Alnwick’s militia depot on Hotspur Street. From census material it would appear the family lived here whilst Eugene was working as a Drill Master on the site. A second daughter, named Emma Jessie Parsons, was born in 1873 and baptised at the same church as her brother but she tragically died during infancy. The family’s grief over the death of their youngest child was soon replaced with joy as a third daughter, Amelia Gertrude Edith, arrived in 1878. She was followed in quick succession by two more girls; Ada Madoline in 1880 and Mabel Violet Florence in 1883. But the birth of Ada was overshadowed by the death of the Sullivan’s eldest daughter, Hannah, occurring in the same year.

By 1885 the Sullivan’s marriage had spanned almost thirty years. It had created eight children, and endured the death of two. It had survived extreme warfare and stretched its affection across three continents. Perhaps the marriage had run out of steam, or perhaps the recent death of their eldest child was too great for the couple to overcome. Whatever the reasoning behind their decision the couple decided to amicably separate in 1885. They hired the Dickson, Mornington and Archer firm (as the Dickson, Archer and Thorp firm was known during a short period in the late nineteenth century) to settle any legal issues relating to the custody and financial support of their remaining children.

Separation and Agreements

The Sullivan’s separation was a unique one, and their micro-case can be used to trace seismic changes occurring throughout the nineteenth century with respect to divorce, women’s rights and familial settlements. Neither party sought a full legal divorce, perhaps because they wished to avoid any reputational shame or financial demands, but instead opted for a legally-supported separation. During their separation neither party received blame or vilification for the breakdown of the relationship. Contrary to the perceived character of an estranged husband, Eugene Sullivan penned letters to his lawyers filled with warm and affectionate words for Emma. However Eugene’s strong emotions were muted within official separation documents, and his actions were revealed to have been more complex. What therefore follows is an analysis of the couple’s official and private documents, framed within the greater concepts of nineteenth century divorce and marriage.

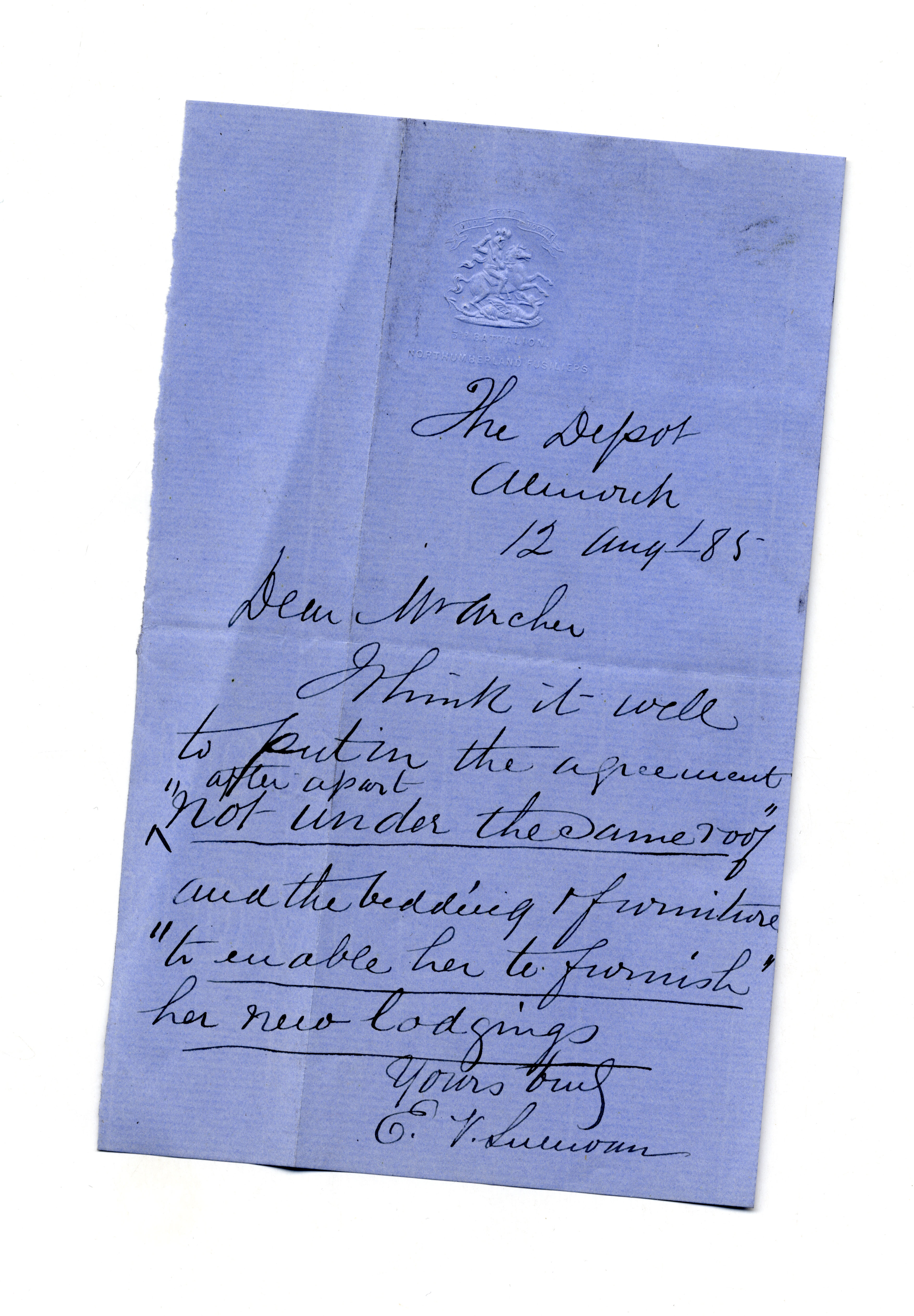

The indenture outlining the terms of their separation cites “unhappy differences” which “have arisen between E.V Sullivan and Emma his wife” as the reason why “they have consequently agreed to live separate (not under the same roof) from each other for the future.” The document was made in the presence of a witness, William Bean, who was to act as Emma’s trustee. Parting to live under a separate roof was important phrasing which Eugene pushed to have included. But the inclusion of the phrase becomes confused when one reads his personal correspondence with the solicitors. In this series of documents Eugene repeatedly emphasises, and encourages, his assumed responsibility to furnish and finance Emma’s new lodgings.

Only four of the couple’s children were subject to the document’s conditions (and a potential custody battle) as, by 1885, two had predeceased the settlement and another two no longer lived in the family home. The document decided, and ultimately divided, custody over the children with the following statement;

“E.V Sullivan shall have custody and shall also maintain and clothe the said Ernest Louis Sullivan and the said Emma Sullivan shall have the custody of Amelia Gertrude Edith Sullivan aged 8 years, Ada Madoline Sullivan aged 5 years and Mabel Violet Florence Sullivan aged 3 years. And that the said E.V Sullivan shall have access to the said Amelia Gertrude Edith Sullivan, Ada Madoline Sullivan and Mabel Violet Florence Sullivan and the said Emma Sullivan shall have access to the said Ernest Louis Sullivan under such arrangements as shall to be made between them for this purpose or if they are unable to agree under such arrangements as shall be made by the said William Bean.”

It is perhaps telling that, whilst custody of the children takes up two pages of the document, references to the settlement of property take up three and a half pages. It was agreed, as part of the separation, that Emma would receive a weekly payment from Eugene, to be handled by her Trustee. However, the payment would be forfeited should the marriage be permanently dissolved by “any other jurisdiction.” This clause acted to prevent Emma from pursuing a total divorce. Regarding the inheritance of property, should Emma predecease Eugene, it was stated that he would inherit as was his “marital right.” The document also noted that Emma should not expect, and would not be given, any further financial support for the payment of future debts or every-day expenditure from Eugene.

But Emma also maintained her own conditions; rooted in her personal freedom and independence. She added a clause that, upon following the separate living arrangements, Eugene could not “molest or interfere with the said Emma Sullivan in her manner of living or otherwise.” This clause throws Eugene’s ‘caring’ letters into question. Was he really trying to provide for his estranged wife, and the children she maintained, by keeping her financially and furnishing her new abode? Or was it a way to maintain a level of control over Emma? The inclusion of so many specific clauses appeared to insinuate that, at least for Eugene, the bonds of marriage relating to property and name remained – even if the couple occupied separate lodgings.

Nineteenth Century Divorce and Marriage

During the nineteenth century the concept of divorce and marriage underwent drastic legal change. Marriage became more secular following various parliamentary acts. This drove separation and divorce out the ecclesiastical courts and into the jurisdiction of secular judges and solicitors; such as Dickson, Archer and Mornington. Married women were also afforded greater legal status as the century progressed, with specific regard to the custody of children – developments Emma clearly capitalised upon.

Prior to the latter 1800’s ecclesiastical divorce could be granted in extreme cases of adultery, cruelty or desertion although no party would be allowed to remarry. In 1857 the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act created a Probate and Divorce Court in London which allowed civil divorces. When using these courts parties still had to prove, with sufficient evidence, that serious adultery, cruelty, incest, bigamy or other heinous offences had occurred. Unfortunately, evidential proof was often difficult to establish and pursuing a divorce case could be costly to ones finances and reputation. There was no reference to ill-treatment or adultery in the Sullivan’s case, and perhaps this lack of vilification can be attested as the reason why a full legal divorce had not been sought.

The Married Woman’s Property acts of 1870 and 1882 gradually gave married women the right to hold property in their own name. The 1882 act gave women possession of all property held before or after their marriage – thus allowing women to become independent financial entities. But this still did not entitle married women to sue their husbands (as they remained one legal person) or be allowed to keep a legal residence apart from her husband. Thus Eugene’s acceptance of his wife’s second residence, forming part of a legal separation, was a double-edged sword. Although it allowed Emma to live a separate and more autonomous life, it would doubtlessly have been poorly judged by their contemporaries.

The Sullivan’s settlement had been carefully crafted by both sides to suit the middle ground between marriage and complete divorce. The document mediated between both sides, by allowing Emma to keep a separate residence and splitting custody of the children, as well as feeding into broader changes and trends. Emma therefore benefited from legal change and shifting social perceptions.

A Happily Ever After?

In the years which followed their separation neither party pursued an official divorce. Eugene retired as a Drill Master in Alnwick and moved across Northumberland; from 65 Beaconsfield Street in the ward of Arthur’s Hill, Newcastle Upon Tyne to Westgate.

In 1891 the couple appear to have either reconciled, or at least agreed to cohabit, with their extended family. The couple can be found on the census living in Westgate with their son Ernest Lewis. Ernest had returned to the family home having been married at 17 and widowed, during the birth of his son, at 19. Also living in the new family home were daughters Amelia, Ada and Mabel.

The family did not live in the Newcastle area for long, as they subsequently moved onto Alnmouth. Eugene died shortly after the move, in 1896, whereas Emma was still living in the area in 1911 at the age of 71. She peacefully lived out her final days under the care of her eldest son, William, in Alnmouth’s Percy Cottages on Front Street.