James was born in County Durham, but brought up in Northumberland. At the age of three, he was with his mother at Red House Farm, Monkseaton and by age seven, he was living with his grandparents in Ashington where he attended the Hirst North Boys School until leaving at twelve years of age. His first job was as a lather boy at a local barber shop and at age fourteen he was working at Woodhorn Colliery, Ashington.

By December 1914, James had enlisted and was placed in the Northern Cyclists 2/1st Battalion, ‘C’ Company, commanding officer Captain Alister Hardy. The Cyclists Battalions were primarily a Home Defence Unit and also provided trained men for the regular Army – usually the infantry.

By December 1914, James had enlisted and was placed in the Northern Cyclists 2/1st Battalion, ‘C’ Company, commanding officer Captain Alister Hardy. The Cyclists Battalions were primarily a Home Defence Unit and also provided trained men for the regular Army – usually the infantry.

‘C’ Company was billeted in Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland, for training and for coastal defence both south and north of the Castle. Christmas Day, 1915, saw the Norwegian barque Lovespring floundering off shore with the crew being rescued by the steamer Copsewood and as the Lovespring broke up, some of the cargo was salvaged by C Company.

Early 1916 saw ‘C’ Company being relocated to Chapel St. Leonards, near Skegness, Lincolnshire, where once again, they were used for coastal defence, building trenches and outposts in readiness for a possible invasion. It was here that James met his future wife, Mahala Hunter

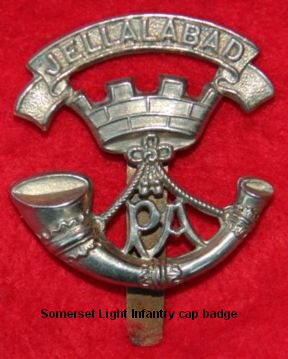

It wasn’t long before James found himself being transferred into the regular Army; he was placed in the Somerset Light Infantry and was shipped to the Western Front. Like many infantrymen, he was wounded and was returned to England for recuperation. When declared fit, he returned to France as a Corporal where for a short time he was a guard at a POW camp.

It wasn’t long before James found himself being transferred into the regular Army; he was placed in the Somerset Light Infantry and was shipped to the Western Front. Like many infantrymen, he was wounded and was returned to England for recuperation. When declared fit, he returned to France as a Corporal where for a short time he was a guard at a POW camp.

Mid 1917 found James back in England where he was placed in the Labour Corps – a common practice for soldiers who were deemed to be unfit for service at the front line. It is thought that James never fully recovered from the wounds he suffered in 1916. James was stationed in Seven Oaks, Kent and in November 1917 he was allowed to return to Mahala’s home village where they married in the local church. After a very short time together, James returned to his unit in Seven Oaks and remained there until the end of the war.

After demob, James returned to Mahala in Lincolnshire and then in late 1919, he brought his wife and his two young daughters back to Northumberland where they lived in Hollymount Cottages, Bedlington with James working at a local colliery. Circa 1923 found the family moving across to Ashington and to a newly built house in Garden City Villas with James working at Woodhorn Colliery where he worked until retiring at age 65.

Every year in late October / early November, James’s old commanding officer, Captain Alister Hardy, (now a Professor in Marine Biology and later to be knighted in 1957) hosted a reunion dinner for surviving members of ‘C’ Company. James attended each and every year with his final attendance being in 1971.

James passed away at his home in Garden City Villas in December of 1972, having been survived by his wife, Mahala who later died in 1977.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Allan Robinson in supplying this article for the Northumberland At War Project.