Several of the patients from Stannington suffered from fractures, identifiable in the radiographic images.

Case Study 1

Patient 132/1951 is one such patient with a fracture to the distal right femur (thigh bone just above the knee joint). The patient’s file states that the fracture was caused by a fall in a corridor at the Sanatorium, where the individual was being treated for tuberculosis of the hip.

Figure 1 shows the fracture around the time of breakage, with displacement in alignment of the bone shown particularly in the anteroposterior image on the right.

Figure 2 shows the fracture whilst the patient was in plaster, identified by the thick white line surrounding the leg and the distorted quality of the image. Despite this poor quality, healing of the fracture can be seen in the slight bulge surrounding the initial breakage just above the knee, this is due to new bone growth during the remodelling stages of healing.

Figure 3 was taken some months after the trauma occurred. At this point the fracture is fully healed. Periosteal thickening (new bone growth) can be seen surrounding the location of the fracture, but it is unlikely the individual suffered any visible deformity or any mobility issues.

Case Study 2

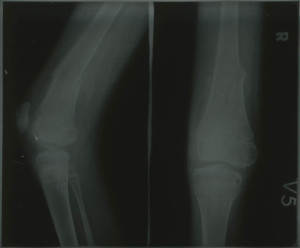

Patient 90/44 was admitted to Stannington Sanatorium with tuberculosis of the bones and joints, specifically involving the spine. However, one of the radiographs was taken of their leg and identifies a fracture.

This is an oblique fracture, caused by indirect or rotational force, and is seen as a diagonal break to the bone. For this individual the fracture has affected the distal mid-shaft of the right tibia (lower leg), there appears to be no fibulae involvement.

In Figure 4, the image on the left is an anteroposterior (frontal) view of the tibia, where the fracture appears approximately two thirds of the way down the shaft of the bone. The right hand image is a lateral (side on) view of the tibia, however in Figure 4 the image on the right has been taken upside down showing the knee joint at the bottom of the image and the foot at the top, this can be seen the correct way round in Figure 5. The fracture is less clear in this image, identifiable by the slight curve in the lower part of the mid-shaft and a thin line showing the actual fracture through the bone.

Fractures and Tuberculosis

The individuals mentioned here were both being treated in Stannington Sanatorium for tuberculosis of the bones and joints, the first TB of the hip and the second Pott’s disease (TB of the spine). Tuberculosis of the bones is considered to cause weakening, which makes bones more susceptible to fractures and deformities. This increased susceptibility may, therefore, have contributed to the trauma causing the fractures in these cases.

It is also noteworthy that tuberculosis of the bone can also be contracted as a result of a fracture. Trauma, including fractures, can cause reactivation of latent bacteria already dormant within the individual at a focal site with disseminated seeding at the fracture site causing ‘TB complicated fractures’ (Sanjay et al, 2013).

Sources

Meena, S; Rastogi, D; Barwar, N; Morey, V and Goyal, N (2013). ‘Skeletal Tuberculosis following Proximal Tibia Fracture’ in The International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds. http://ijl.sagepub.com/

![NRO 10321-3 [MAG P1]](http://www.northumberlandarchives.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/NRO-10321-3-MAG-P11-239x300.jpg)