BERWICK ADVERTISER, 6 OCTOBER 1916

BERWICK PETTY SESSIONS

A Naval Offender – Edward Hay, leading seaman, H.M. motor launch, was charged with being drunk and disorderly in Church Street. He admitted that he was only drunk. P.C. Spiers said the offence took place at eleven o’clock. Prisoner said he had no ship and no home to go home to, and began to get abusive. – Sergeant Wilson corroborated. – Captain Norman said the whole world owed much to the noble service accused belonged to, and he hoped it would be a warning to him not to come there again.

Drunk and Disorderly – Catherine Lovelle, Berwick, was charged with being drunk and disorderly. She said she had been left a widow 18 months ago, had never applied to the Guardians for relief, and if she had made a mistake she had suffered for it. The Chief Constable said there were 15 previous convictions. These commenced in 1885, but she had not been before the Court since 8th January, 1913. Fined 5s or seven days, and a fortnight allowed to pay.

William Wood, temperance hotel keeper, High Street, was charged with having failed to obscure his window lights on the 26th Sept. He pleaded not guilty. Sergt. McRobb gave evidence as to the offence. The lights came from the back premises and witness was accompanied by P.C. Spiers. It was a white-washed yard, and the light shone very bright. When defendant’s attention was called to the matter he would not listen to the witness, remarking that he could prove different. The lights were reduced before defendant came out.

– Defendant repudiated this, saying he could prove differently. – P.C. Spiers corroborated, and said one window had no blind at all. – Defendant, addressing the Bench, said that the offence had been very much exaggerated. – The Chief Constable said that the defendant had been already admonished. He had no desire to be vindictive and he admitted Mr Wood might have a difficulty in superintending his lights in such a business as he was engaged. – Capt. Norman said defendant had no exercised the care he should have, and he would be fined 25s. Defendant explained that on one occasion the offence complained of was caused by a gentleman who was undressing and going to bed. The gentleman had opened the window, causing the blind to flutter. – The Chief Constable said in such a case the gentleman complained of would be summoned.

RAILWAY CARRIAGES

Mr Smith referred to how strictly we were watched at home and abroad in regard to lights shown a night while all the time at night the railway carriages came along showing quite a glare from the door window. It was absurd for the railway company to order blinds down while having the centre window without any blinds. If any passenger did not shut down the side blinds they were liable to a fine, and yet there were only two-thirds blinded and one third of the carriage a blaze, as that part was opposite the lamps. He thought it ridiculous that the public should be put under these regulations so well enforced on the streets and respecting their houses, and yet these express rains from Edinburgh a blaze of light passing their homes. The whole country was illuminated by the light from trains. It was a shame and disgrace that these rains should go up and down the country in these times so brilliant.

The Chairman – You cannot expect much consistency in Government regulations.

Mr Smith urged the sending of a petition against the bright lights on trains.

Mr Westgarth felt, as did also the Chairman that as good a purpose would be served by the matter being ventilated through the Press. The matter then dropped and his concluded the business.

CHESWICK

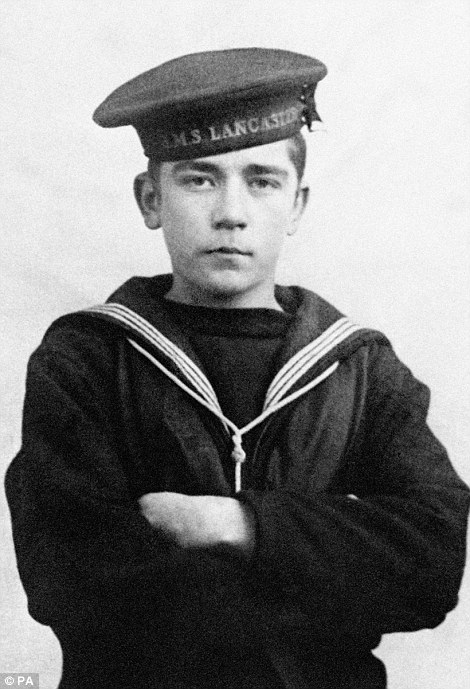

The children of the above school subscribe, four shillings and seven pence towards the

“Jack Cornwell Memorial” on Thursday, September 21st, 1916. I will be remembered the

boy, Jack Cornwell was in the Battle of Jutland, and though losing his life, his heroism will be long remembered. Collections have also been made by the scholars for the National Sailors’ Society, 34 Prince Street, Bristol, a society doing useful work for our sailors. The names of those who volunteered for collecting cards are as follows:- Robert Glahome, Cheswick Farm, 10s; James McLeod, Oxford, 16s 6d; Elizabeth Wedderburn, Goswick Station, 5s 3d; James R. Ferry, Sandbanks, 8s 8d; Robert Johnson, Sandbanks, 5s 3d; James Black, Berryburn, 11s 3d; Joseph White, New Haggerston Smithy, 6s; John Henderson, Cheswick Farm, 6s; Joan Grahamslaw, Windmill Hill Farm, 5; John Turner, Berryburn, 14s; Jane Jackson, Windmill Hill Farm, 5s 3d. The total amount collected, £4 13s 2d, has been duly forwarded to the Secretary.

LOCAL NEWS

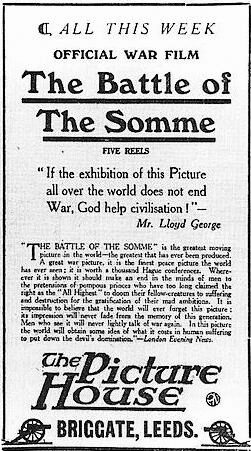

The Playhouse. – The great attraction at the Playhouse this weekend is the exhibition of the great official war film, “The Battle of the Somme,” which the Playhouse management  have secured at great cost. “The Battle of the Somme” is the greatest moving picture in the world, the greatest that has ever been produced. Where ever it is shown it should make an end in the minds of men to the pretentions of pompous princes who have long claimed the right as the “All Highest” to doom their fellow creatures to suffering and destruction for the gratification of their mad ambitions. It is impossible to believe that the world will ever forget this picture. Its impressions will never fade from the memory of this generation. Men who see it will never talk lightly of war again. In this picture the world will obtain some idea of what it costs in human suffering to put down the “Devil’s Domination.” The doors are being opened 15 minutes earlier to allow all seats to be secured previous to commencement. The final episode in the great Trans-Atlantic film, “Greed” will be shown in the earlier half of next week, and it will be accompanied by another powerful drama – “The Vindication.” On Thursday, Friday, and Saturday next week there will be shown “The Wandering Jew, “ a powerful adaptation of Eugene Sue’s world renowned novel and play. The variety entertainment will be supplied by Harry Drew, the famous Welsh Basso in his monologue and vocal – “Over Forty

have secured at great cost. “The Battle of the Somme” is the greatest moving picture in the world, the greatest that has ever been produced. Where ever it is shown it should make an end in the minds of men to the pretentions of pompous princes who have long claimed the right as the “All Highest” to doom their fellow creatures to suffering and destruction for the gratification of their mad ambitions. It is impossible to believe that the world will ever forget this picture. Its impressions will never fade from the memory of this generation. Men who see it will never talk lightly of war again. In this picture the world will obtain some idea of what it costs in human suffering to put down the “Devil’s Domination.” The doors are being opened 15 minutes earlier to allow all seats to be secured previous to commencement. The final episode in the great Trans-Atlantic film, “Greed” will be shown in the earlier half of next week, and it will be accompanied by another powerful drama – “The Vindication.” On Thursday, Friday, and Saturday next week there will be shown “The Wandering Jew, “ a powerful adaptation of Eugene Sue’s world renowned novel and play. The variety entertainment will be supplied by Harry Drew, the famous Welsh Basso in his monologue and vocal – “Over Forty