5th FEBRUARY 1915

MINDRUM

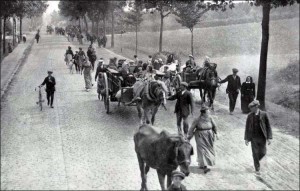

© IWM (Q 53271)

On Thursday, January 28th, a lecture was given in the school in aid of the Belgian Relief Fund. The lecturer was M. Wouters of Antwerp, whose account of his personal experiences of the war was listened to by a deeply interested audience. M. Wouters went through the whole of the earlier part of the war, including the sieges of Liege and Antwerp, and the sacking of Louvain and Namur. Thereafter he was invalided to England.

His account of these terrible times was thrilling and showed what a heroic part gallant little Belgium had played for the saving of Liberty and Civilization. The lecture was illustrated by lantern views of some of the horrors wrought by the ruthless Germans, and concluded with a passionate appeal to Englishmen for more help in men and money. The proceeds amounted to £5, and this will be sent to assist in a small way in relieving the distress prevailing among the unfortunate people the story of whose self-sacrificing bravery will forever “re-echo down the long corridors of Time.”

GIFTS FOR SICK SOLDIERS AT BELL TOWER HOSPITAL

Mr Robertson, books; Miss Pearson, eggs; Mrs Young, St Leonard’s Cakes;Miss Weatherhead, 31 Castlegate, eggs; Miss Herriot, scones; Miss Tait, Bridge Street, currant loaf; Miss B Fair, illustrated papers; Mrs Wilsden, The Elms, apples and oranges; Miss Alder, Halidon, soup; Miss Wood, Horncliffe, beef jelly; “A Friend”, morning papers; “A Friend”, bananas; Mrs A. Darling, Bondington, scones; Mrs Herriot, Sanson Seal, cakes; Miss Herriot, do, loan of gramophone and records; Mrs Gemmel, 25 Low Greens, daily papers and vegetables; “A Friend”, Two puddings.