Blog 3: Final Findings-Phipps Collection

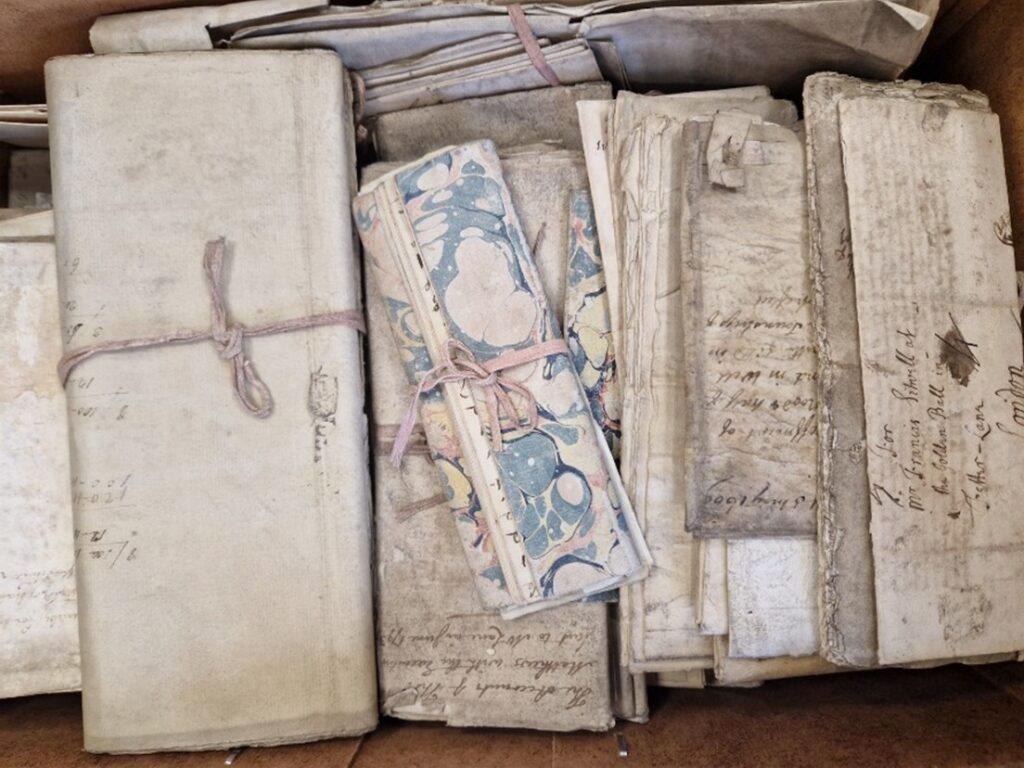

I have now completed cataloguing the Phipps collection, which if you have been following my earlier blogs has produced some rather interesting finds. I recently presented a talk on the findings of the cataloguing project, which gave me a real opportunity to reflect on what I’d been able to find out about Samuel Phipps from the documents in his collection, and this blog will detail those findings.

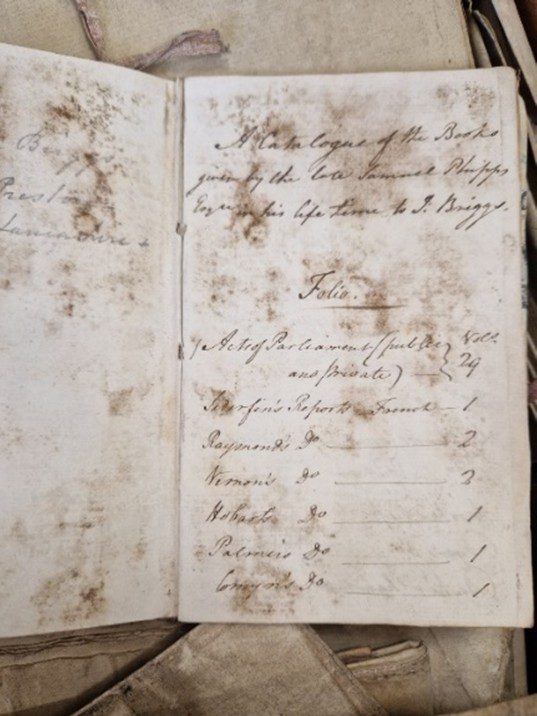

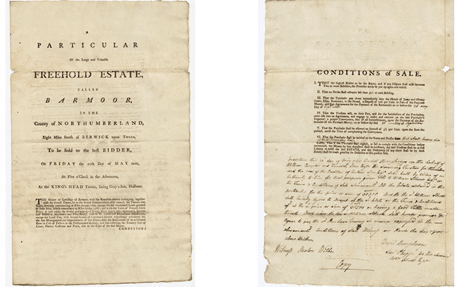

One of the most important aspects of cataloguing an estate collection is a good understanding of the family involved. Ideally the estate owners’ birth and death dates, when they owned their property, how they acquired it, who were their ancestors, and did they have any heirs? Interestingly, with this collection, some parts of that information remained hidden, indeed, it wasn’t until my talk, when I met a gentleman who had also researched Phipps that I was able to establish a date of birth for Samuel Phipps – in my research, he remained elusive. Samuel Phipps was born in 1733 and died in 1781 making his age at death 48. A search through some local history books gave us the descent of one of Phipps’ properties, Barmoor Estate. In the 1912-1915 Berwick Naturalist’s Society Book, it states rather mysteriously that Barmoor was ‘acquired directly or indirectly’ from the representatives of the Bladens, by Samuel Phipps. This implies they were unsure of how Phipps came to own the property. The answer to this question came about in an unexpected place – I was reading a set of sales particulars for Barmoor estate, when I spotted a handwritten note on the second page (see below).

This inconspicuous looking bit of text tells us that Barmoor Estate was purchased by William Sitwell (Phipps’ great uncle), from Fenwick Stowe, for £30,500. Today that would be about £2,626,187.25. The note mentions that the transaction was witnessed by Samuel Phipps. In Phipps’ will, he notes that he inherited Barmoor from William Sitwell, though it should be noted that Sitwell’s will only states that he bequeathed the sum of £10,000 to Phipps, he does not mention the estate. We can at least infer from this that Phipps inherited the estate from Sitwell, though the wills perhaps explain the woolly explanation given in our history book.

Phipps died without issue and Barmoor was inherited by his second cousin, Francis Hurt, who later took on his maternal family name of Sitwell. We also know from some family history research, that in addition to the Sitwells, Phipps was also related to the Reresby family of Ecclesfield, through his maternal line.

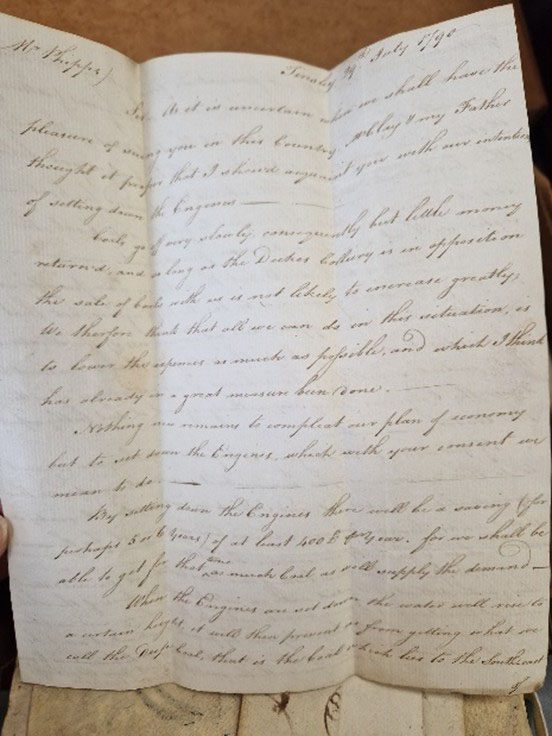

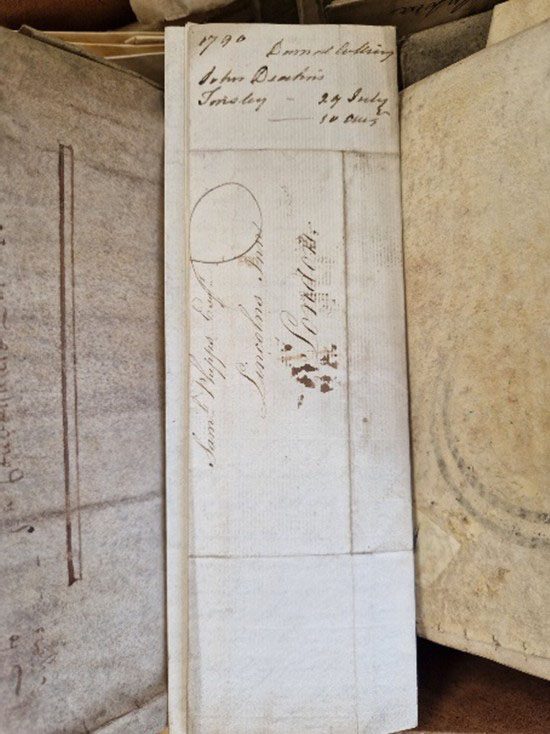

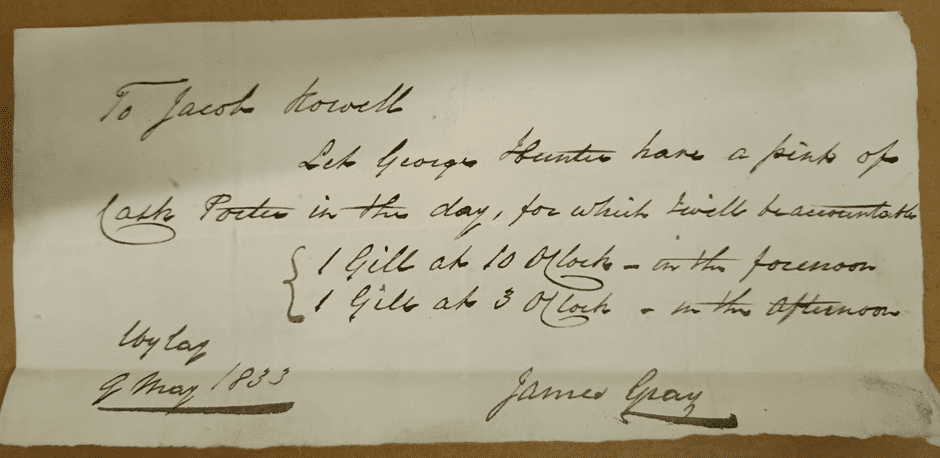

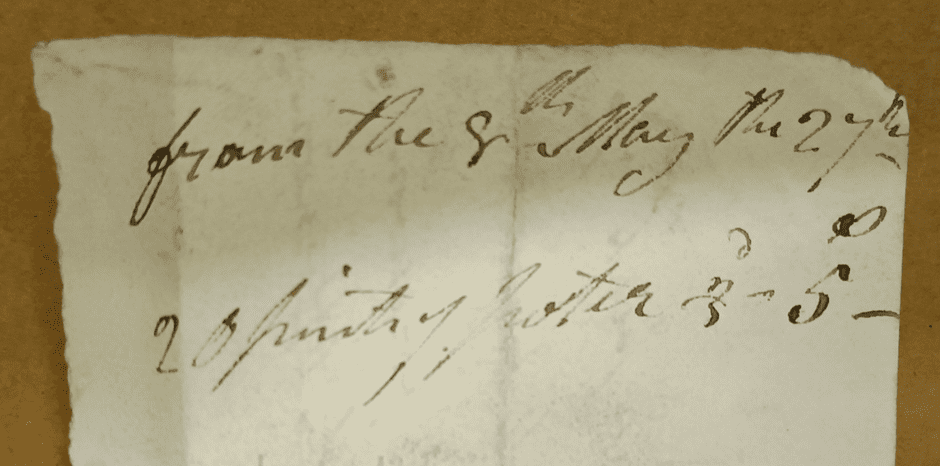

Phipps held extensive property, this much is clear from his records and from his will. Much of the land was in Northumberland, including Barmoor, Yeavering and Coupland, but there was also Ferney Hall in Shropshire, and estates in Yorkshire and Derbyshire amongst others. His main base appears to have been at Lincoln’s Inn, Middlesex, where he practiced his business as a barrister, though we have plenty of receipts for travel, showing that he visited his other properties. Examples include these rather lovely hotel receipts (below), for example, which tell us that ale would have cost Phipps 6 pence in North Allerton, but surprisingly only be 3 pence in Harrogate!

When I first opened the boxes in this collection, nothing was in any kind of order, so all of this information was very useful to help me to identify how the material should be arranged. I could separate out the material into the various estates, and I could understand why letters from the Sitwells and Reresbys were found in the collection. I could also start to separate out records which related solely to Phipps work as a barrister, and not to his own land holdings.

One of my favourite aspects of this collection was the sheer number of purchase receipts, and the detail they provided about Samuel Phipps as a person. We do tend to focus on the running of estates when looking in these sorts of collections, and it can be easy to forget that we’re looking into the history of a real person. These receipts bring Phipps to life and can also tell us about the life of a wealthy gentleman in the late 1700s.

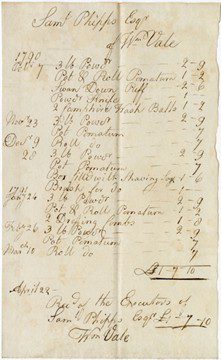

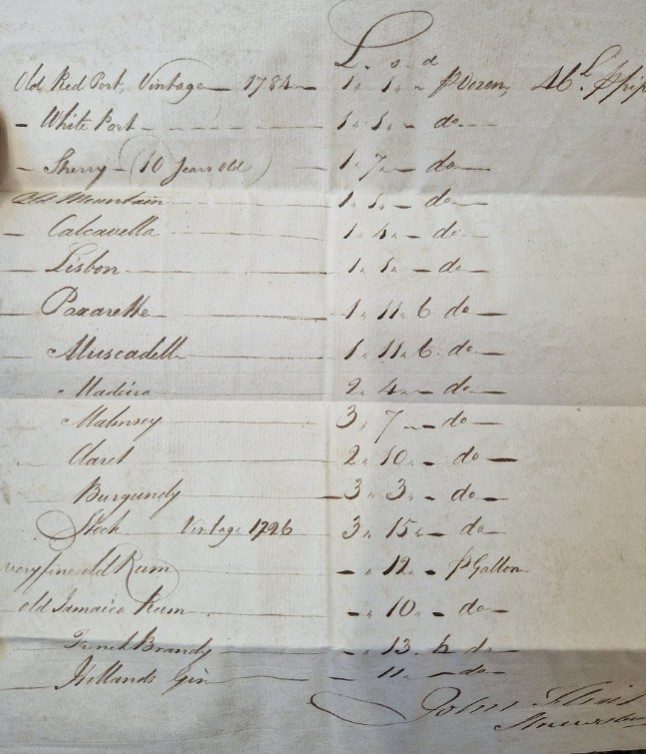

There are documents like this perfumier receipt for 1790-1791 (below left). Phipps died in 1791, so these we his final months, but even at that time he’s buying a ‘swan down puff’, ‘powder’ and multiple pots of ‘pomatum’ (used to slick down hair) – fashionable to the end! We also have a wine list, which includes Madeira, a popular wine at the time, but also a 1726 stock vintage wine for £3 and 15 shillings, or £241.80 in today’s money, he seems to be a man of expensive tastes.

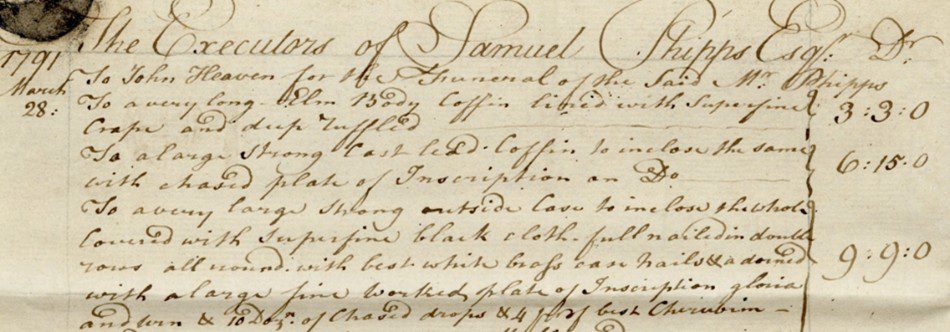

One account which divulged a surprising amount about Phipps, was his funerary expenses. The list is very detailed and not only tells us a lot about what might be included in a gentleman’s funeral at the time but also gives us some idea about Phipps’ physical appearance. Unfortunately, our collection does not include a painting or likeness for Phipps, so this is the closest that I came to having an idea of what he looked like, albeit in quite a morbid fashion! If you look at the image below, which is a snippet of funerary expenses from the appropriately named ‘John Heaven’, the first entry is for a ‘very long Elm Body Coffin lined with superfine Crape and dup ruffled’. The latter terms are archaic spellings of ‘crepe’ and ‘dup’ fabrics, both popular with funerals at the time. Note that they are ‘superfine’ implying a higher-grade fabric. We can also see from the term ‘very long’ that Samuel Phipps was a tall gentleman, at least for the time. Later in the same document, there is an expense of a ‘very large fine quilted mattress for the body to lay on’ – again ‘very large’ implies quite an imposing gentleman.

NRO 2372-G-1-2-1-1-004 – Phipps’ funerary expenses

All of the fabrics noted in the expenses, seem to be of the highest quality, and this even extends to those working at the funeral. One entry is for ‘6 rich Black Silk Scarfs for Ministers, Clerk, Steward, Apothecary, and Undertaker’, these set the executors back £15, which in modern currency would be £861.46 – more than the cost for his coffin!’ Not to mention what would be an additional £60 in modern money just on ostrich feathers to decorate the procession.

We can also use these expenses to gain a bit of an understanding of funerary arrangements in general. In this same document, towards the bottom of the list, we find ‘The usual allowances for Beers for all the Inn porters and under officers’, this implies it was an expectation at the time to provide that. We also find a payment for two ladies to sit ‘up with the corps: 5 nights & 5 days’ – that’s quite a wake! Perhaps this was as much to protect the fine garments and funerary items as the body. The final fee for the funeral was £127 10s 7d (£10,980.84 in modern currency) with an additional £10 (£861) for the gravestone.

From these expenses, Phipps appears to have been affluent and fashionable, and this may inspire an almost Dickensian image of a rich gentleman, though Samuel Phipps appears to have been a very charitable man. The collection includes letters and accounts which can tell us a bit about Phipps’ personality. In one such account, Thomas Johnson owed Samuel Phipps a debt for £473 3s (£40,826.45 in modern currency). Despite this sizeable debt, a note added to the account shows that Phipps ‘advanced for the support of Thomas Johnson, his wife and children £9 19s 6d’ that would be nearly £860 today, so it’s a significant additional sum given by Phipps to ensure Johnson is still able to provide for his family. There are sales particulars included with this account which show that Johnson, a coach-master, did eventually have to auction off his household furniture to pay for the debt. From a historical perspective, this is interesting in itself, though for a property in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London. Included in the inventory are ‘crimson check furniture’, ‘A set of 3 beautiful, rare old Gold Japan image bowls’ and ‘a large hair trunk’ – I’ll admit the latter concerned me on a first read but I’ve since learned that this is a leather trunk where the hair hide remains!

We do have a copy of Phipps’ will, though is very fragile and hard to read. Fortunately, there is a scan of the original available online. This tells us that in addition to his charitable nature in life, he bequeathed annuities (annual payments) to many of his servants in sums of up to £30, ensuring their care after his death.

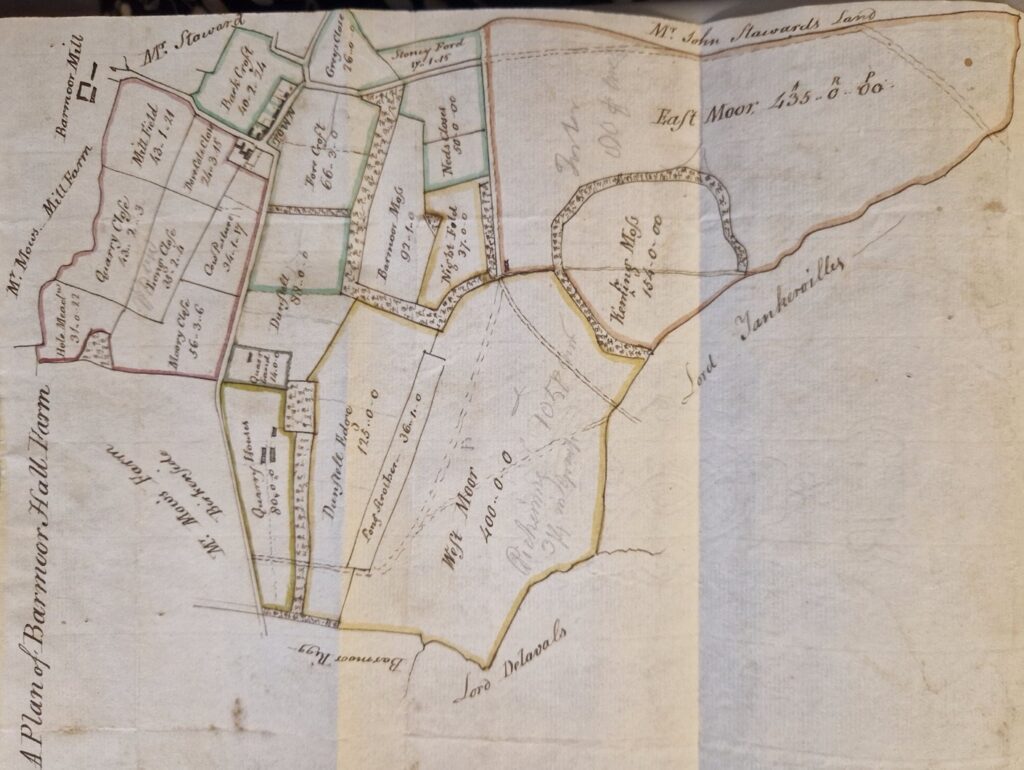

In the Phipps collection there are many estate records and surveys, so anyone from the Barmoor, Yeavering or Coupland areas at least should be able to find out some information about their local area in the collection. As this is a cataloguing project, I was not able to spend too long researching the records I found, but I will mention here that we had some finds like the sketch below.

Sketch and plan of an un-named property in Yeavering (undated).

While I don’t know much about this property, indeed the sketch is even undated and I can’t say for sure if the property still stands, but this remains a fascinating find. It’s not the only sketch or plan found in the collection which may hold answers to one of your questions.

I hope this blog has given you an idea of some of the information you could find if you researched this collection. You may have an interest in the local area, in everyday life in the 1700s, or specifically an interest in Phipps and his family, all of these topics can be researched in this collection. The Phipps collection has been catalogued and this catalogue will be going online in the next two months, so do look out for that.

The project was completed with funding from the NACT and the Community Foundation Windfarm, with support from Northumberland Archives, so I will end with a final note of thanks – without that funding this collection would remain uncatalogued and these findings would still be a mystery.

Beth Elliott, Project Archivist