Since the medieval period relief to the poor has played an important part in the development of society. It was not until the time of Elizabeth I that it was governed by a legal statute which determined who was eligible for relief and under what circumstances they would receive it. The surviving records can provide a fascinating insight into how ordinary people lived and the general movement of the population historically. Over a series of posts we will highlight some of the most commonly used poor law documents in our collection.

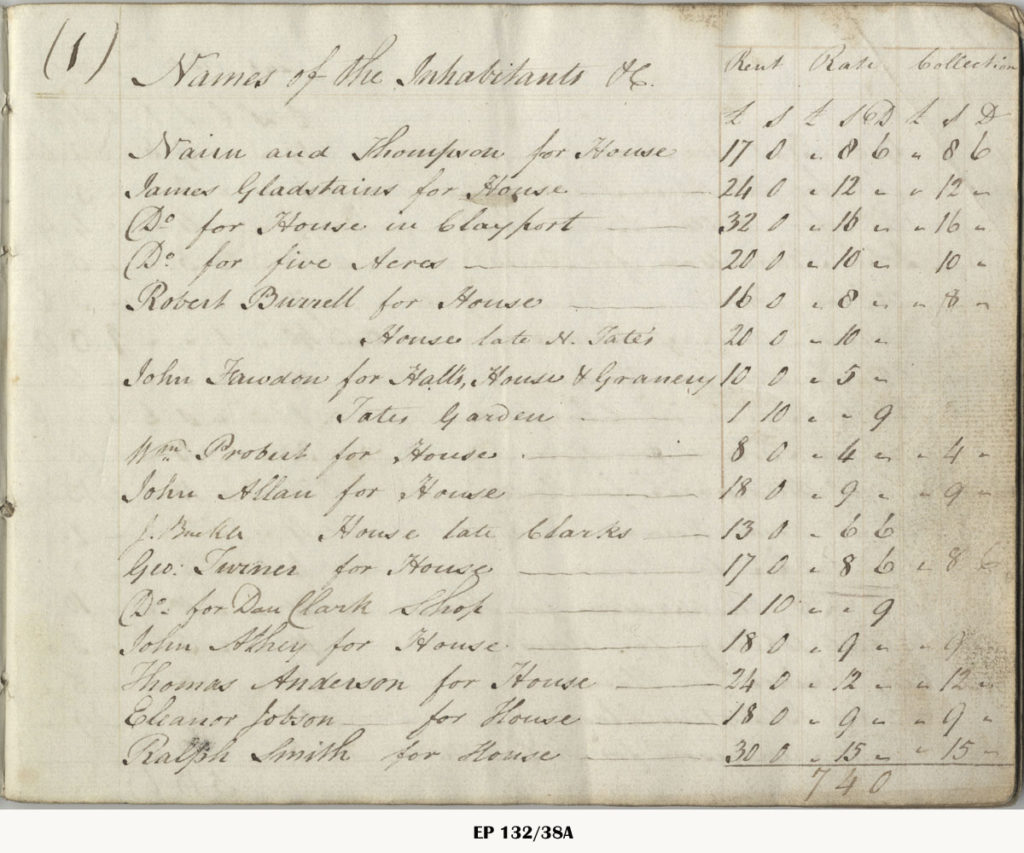

Poor Rate

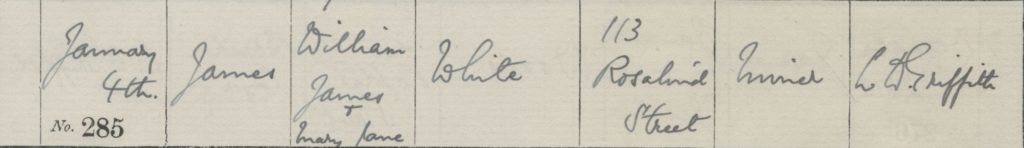

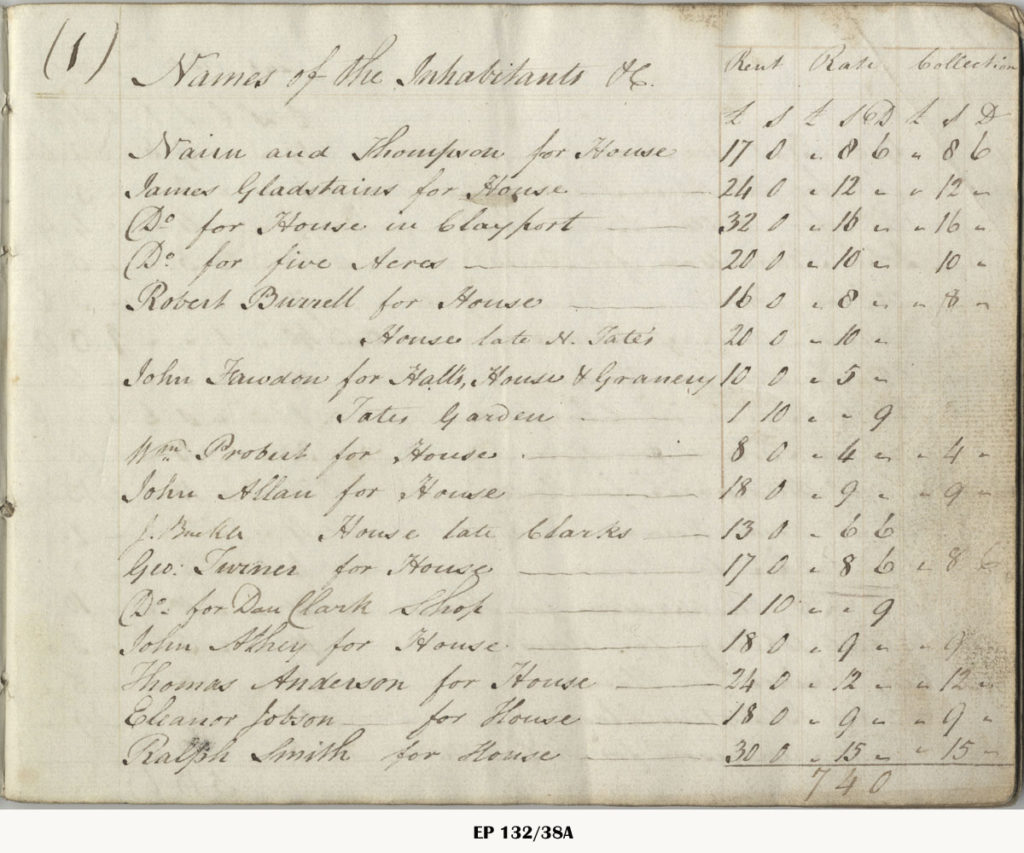

Money was raised to support the poor of the parish by the charging of a local parish rate, or tax. The money raised was used by the Overseers to support the poor. This example is a copy of the first page from the Alnwick Poor Rate register of 1768.

It lists the names of those Alnwick residents eligible to pay poor rate. It provides some detail about their property and notes the rent and rates payable on the property. This information is then used to calculate how much poor rate is payable – the figure in the last column.

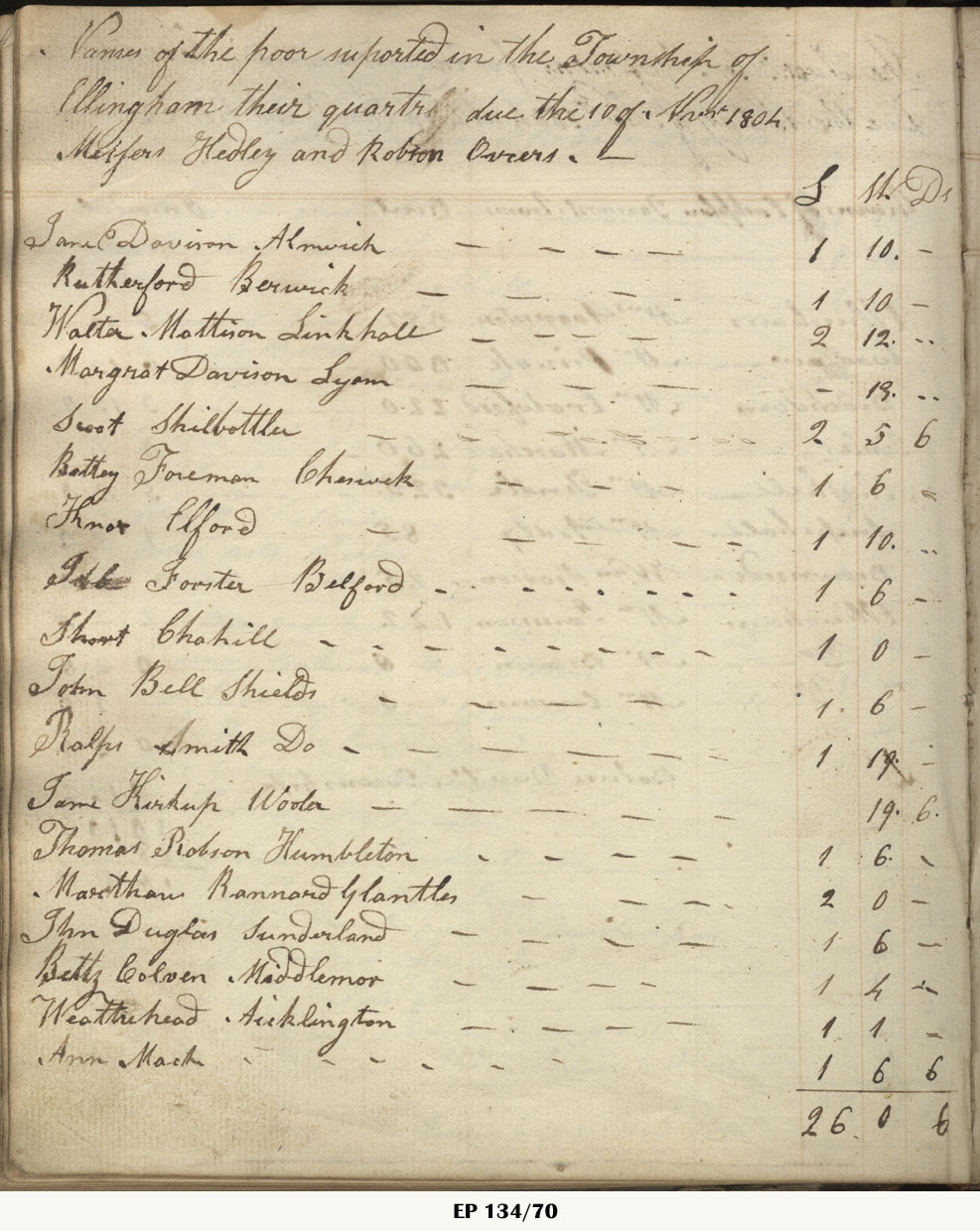

Overseers Accounts

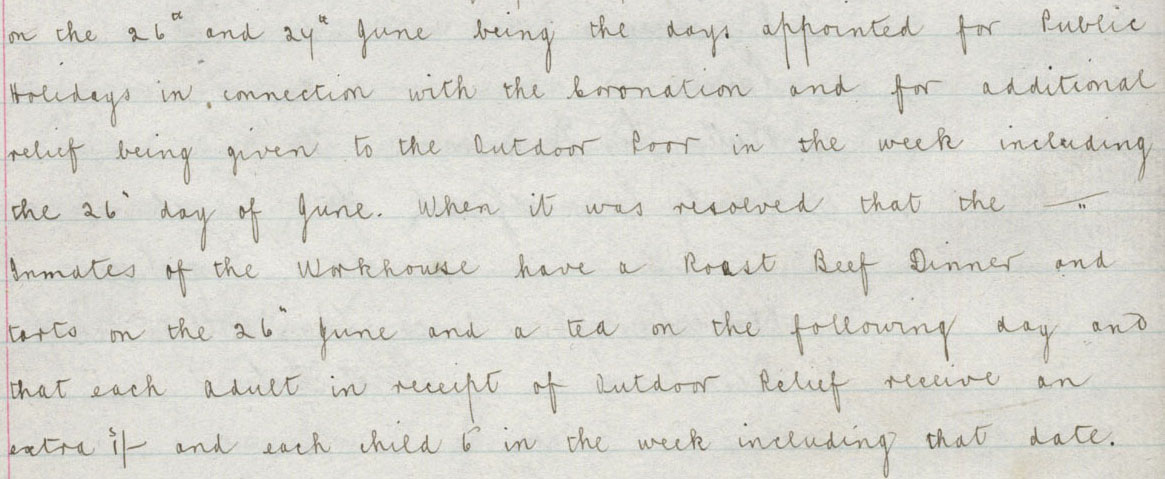

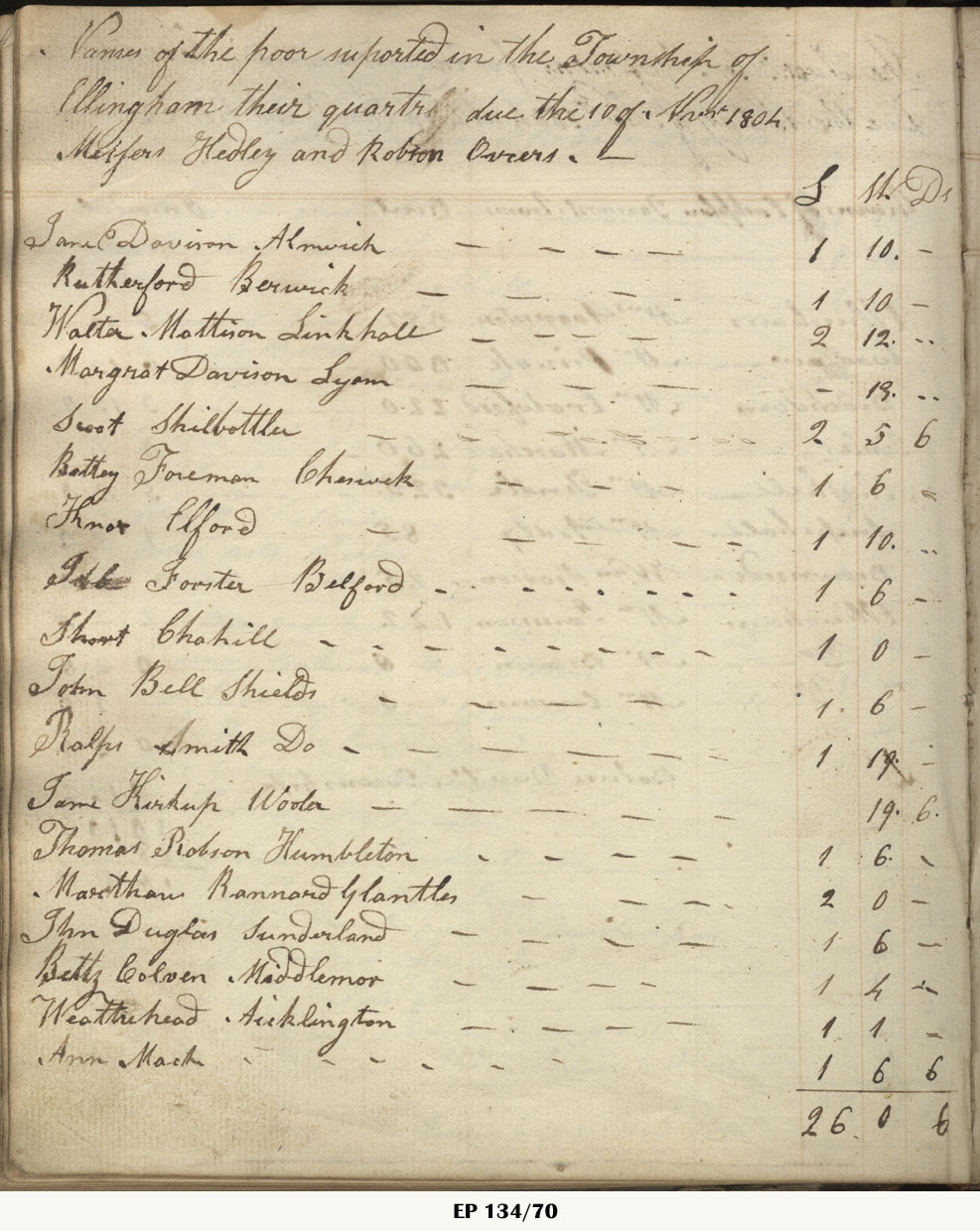

The Overseer kept accounts of how money collected was spent. This page from an Account Book of 1786-1816 shows one of several references to Ann Mack within the volume. It would be possible to work through the volume and discover when Ann first received payment and then when payment was ceased.

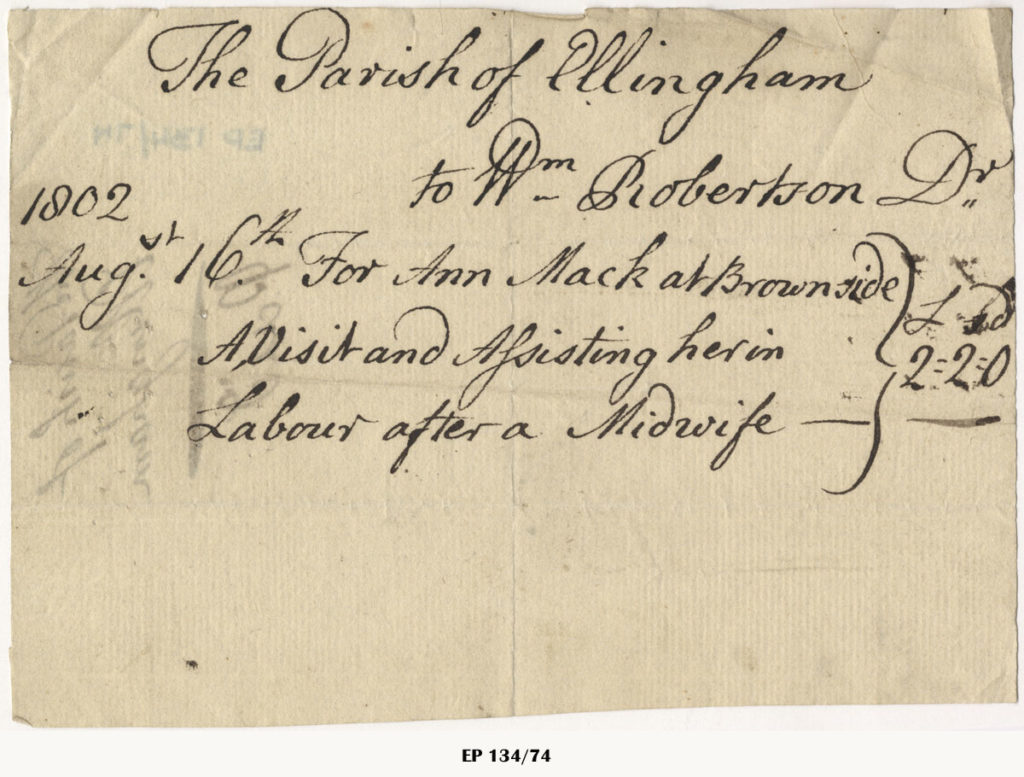

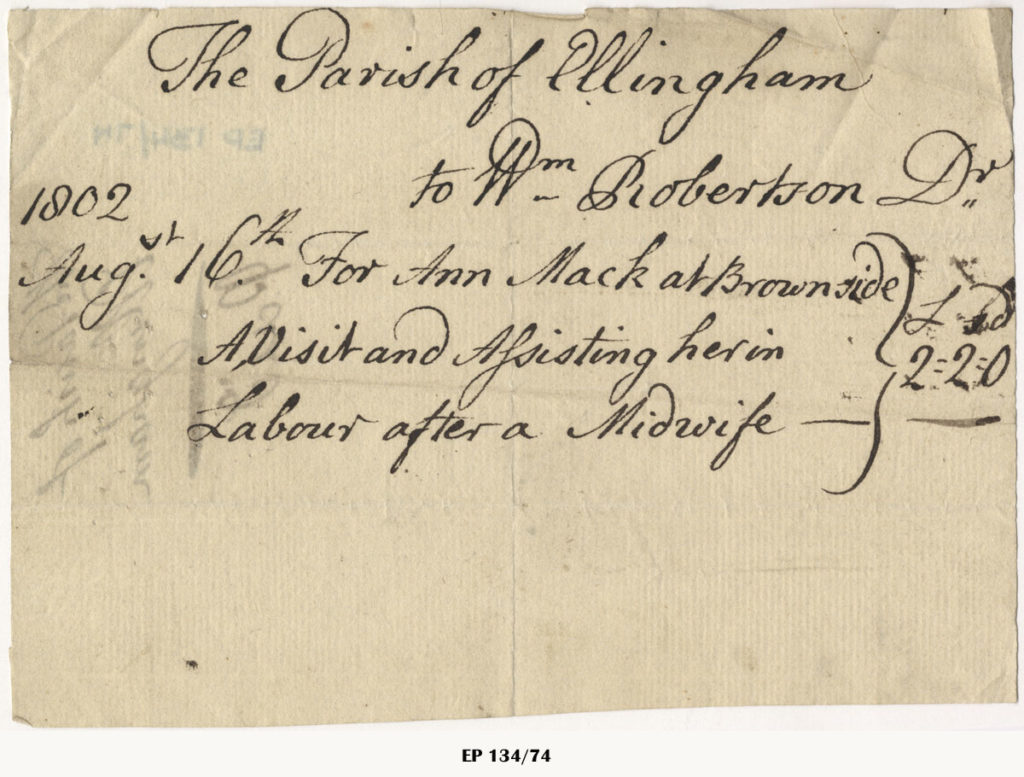

Sometimes it is possible to locate vouchers or receipts relating to particular cases dealt with by the Overseers. Below is a copy of a receipt found in the Ellingham parish records recording expenses incurred in the delivery of a child to Ann Mack in 1802.

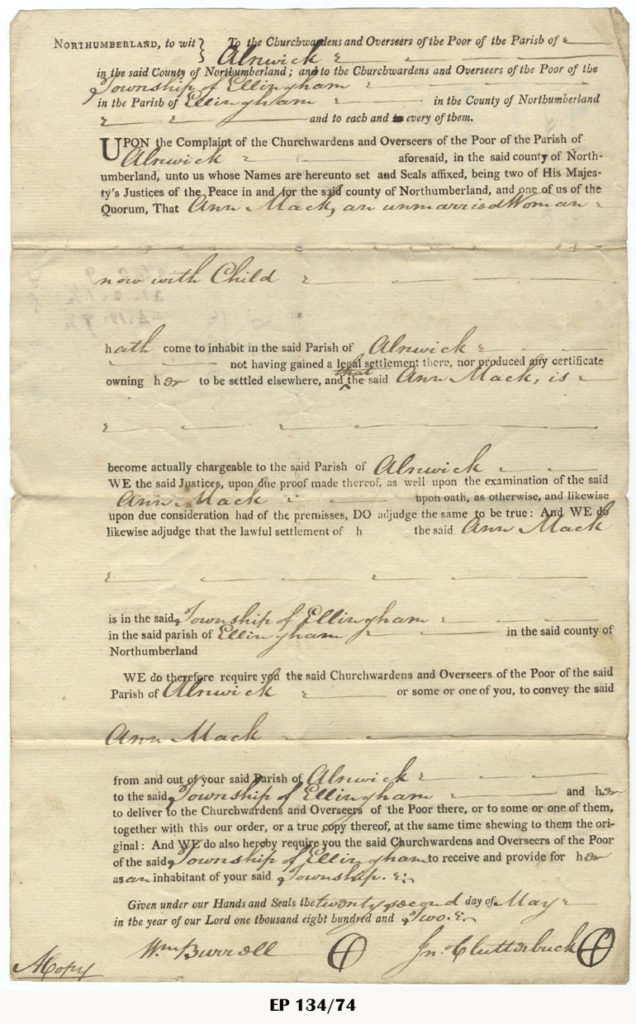

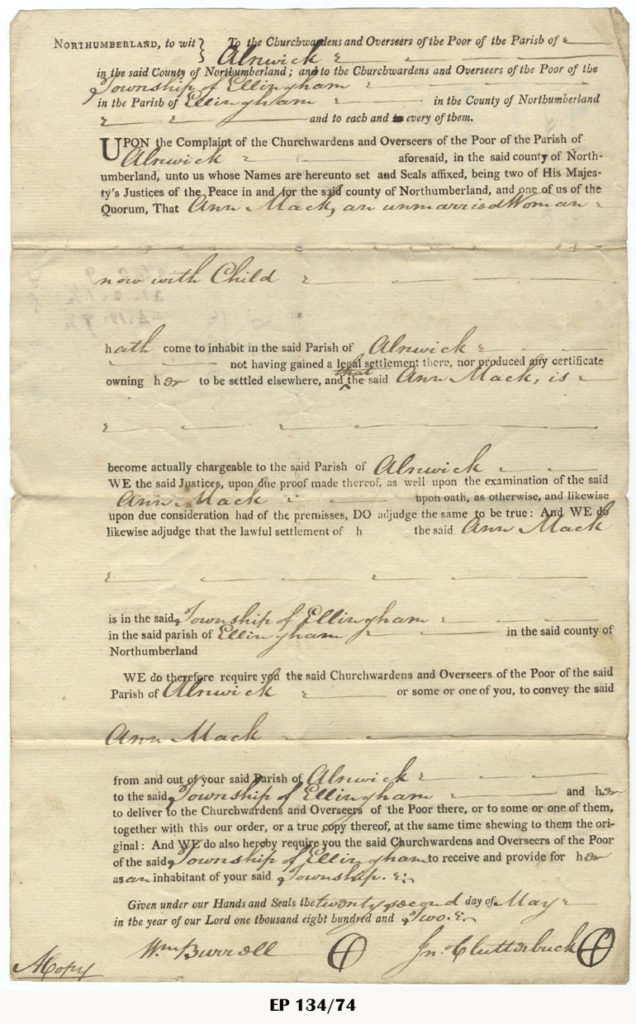

Removal Orders

The removal system was one way of ensuring that large numbers of the poor did not become dependent upon the parish and their ratepayers. Everyone was expected to have a legal parish of settlement. If the place where you lived was not your legal place of settlement and you were unable to support yourself and your family, you could be removed to your own parish. This is a copy of the removal order relating to Ann Mack in 1802.

On the date that the order was issued Ann was resident in Alnwick parish. The document states that Ann’s legal parish of settlement was Ellingham, an adjoining parish to Alnwick. Sometimes after a person was removed, they returned to where they had lived. Within our collection of removal orders there is a second one for Ann Mack issued in 1806, four years after this order was issued. Both request that Ann should be physically removed from Alnwick to Ellingham.

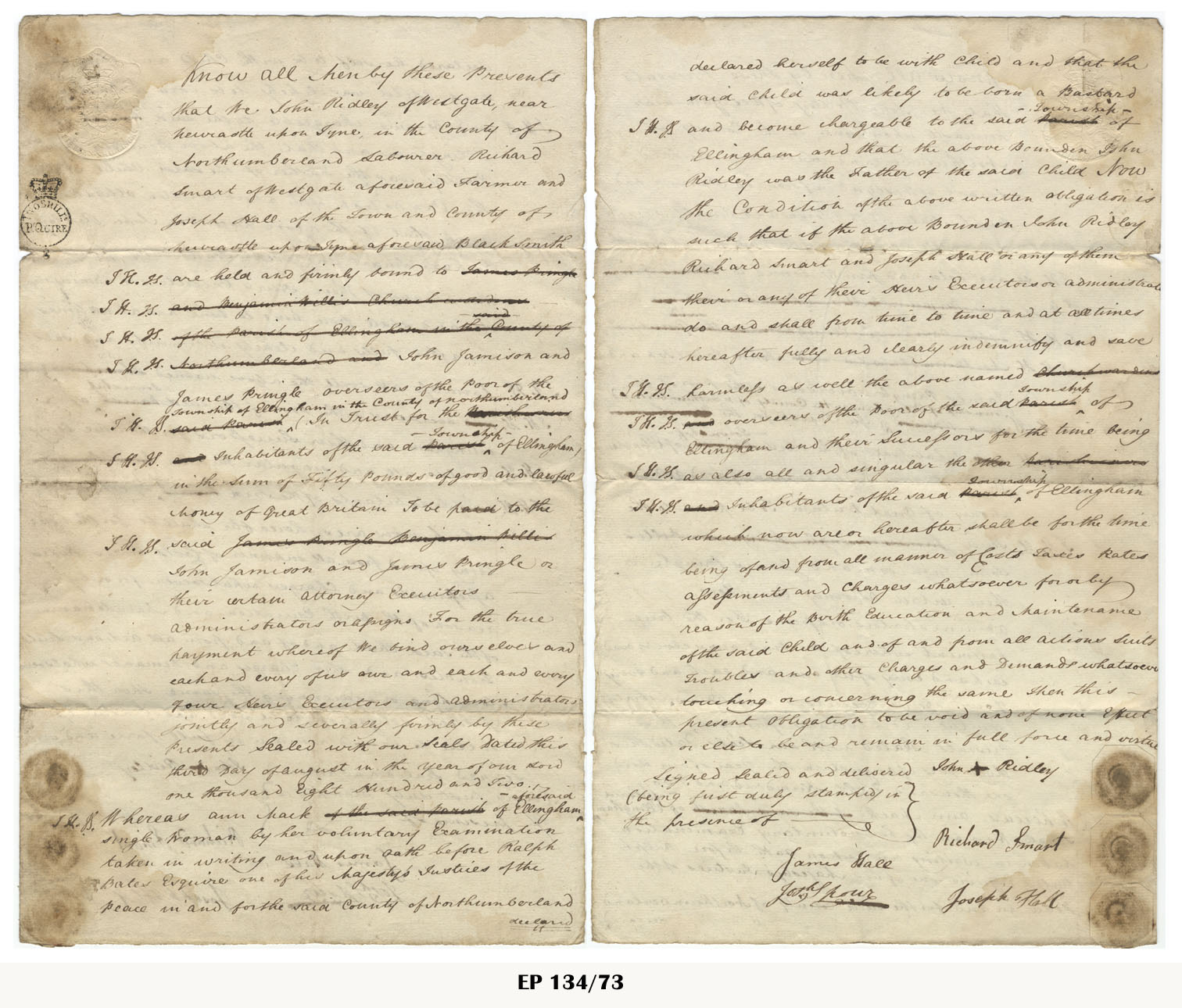

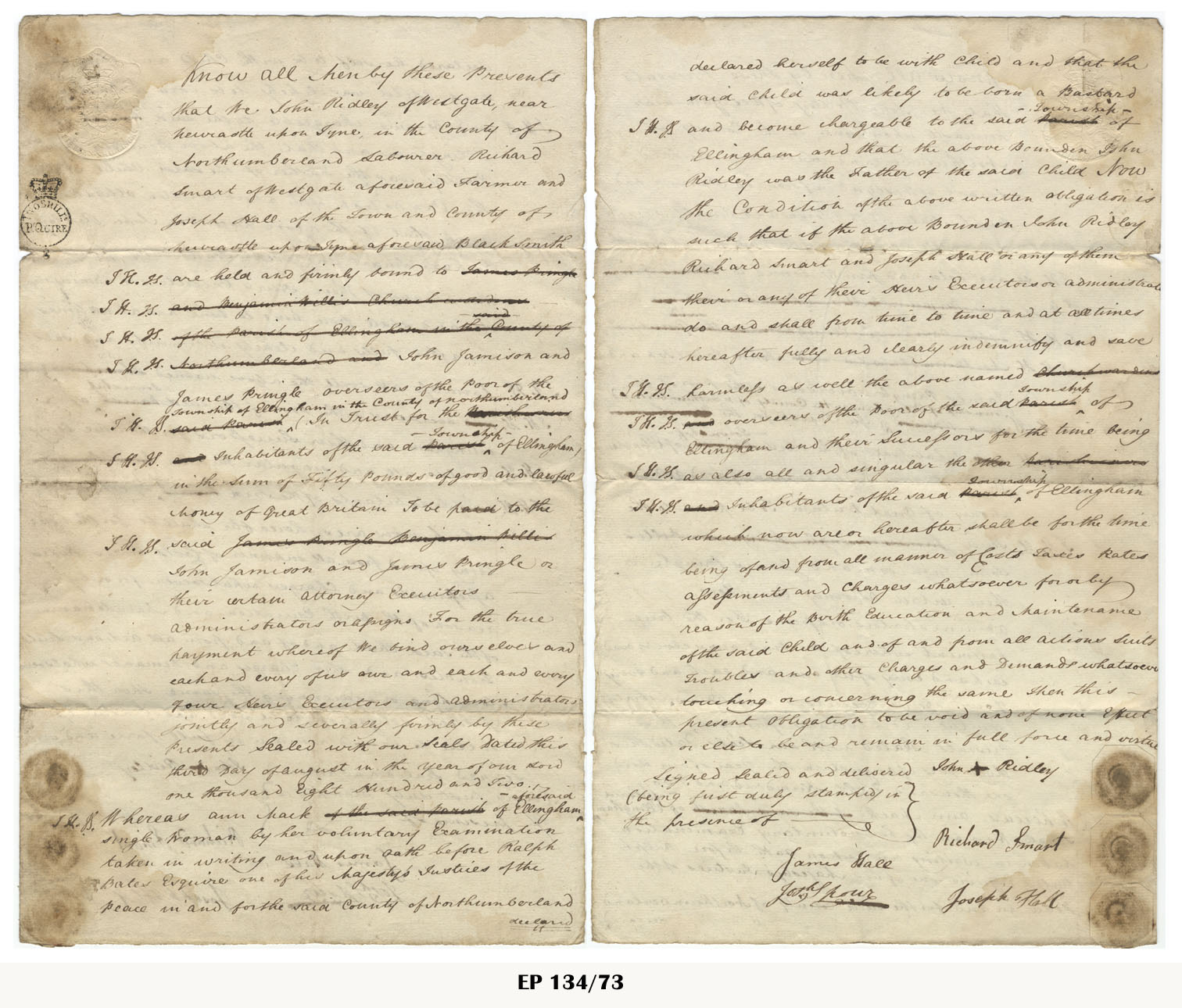

Bastardy Bonds

If a mother was unable to provide for her illegitimate child, the parish had to take financial responsibility for supporting it. The mother was expected to reveal under oath to the Overseers the name of the child’s father. A bond was then drawn up and the father of the child was meant to agree to provide the ’lying in’ expenses of the mother as well as maintenance for the child in the future. In this way the Overseers tried to avoid yet more financial demands being placed on the parish. Below is a copy of the Bastardy Bond issued by the Overseers of Ellingham parish in relation to the illegitimate child of John Ridley and Ann Mack.

The child was unborn at the date the bond was issued and is therefore not named. (In some bonds the child has been born and a name can be discovered.) The father of the child is named as John Ridley, a labourer, of Westgate, near Newcastle Upon Tyne.

The names of two other men are given in the document – Richard Smart, farmer, of Westgate, Newcastle Upon Tyne and Joseph Hall, Blacksmith, of Newcastle Upon Tyne. These men stood as sureties to the bond so were responsible for supporting the mother and child if the father ran away or failed to pay support. Sometimes the bondsmen were relatives of the father of the child. Using Bastardy Bonds is one way to try and trace an illegitimate ancestor in a family, however not all bastardy cases resulted in the drawing up of a bond. Sometimes the case was settled without the involvement of the parish. Even when the parish was involved, many Bastardy Bonds have not survived.