Up until the 19th Century, memorials to the dead were usually the preserve of the wealthy. The introduction of burial clubs, offered by trade unions, religious societies and friendly societies, enabled many working class people to have a proper burial. At this time, those who died through some tragedy were often commemorated by the friends and relatives to raise funds for the victim’s dependents. The etching of cheap glassware to memorialise mining disasters, and the profusion of printed material, in the form of memorial cards and silk bookmarks, was a way to remember the victim and to give charity to the family.

Very few memorials seem to have been made to remember people who died through disease throughout this period. Asiatic cholera, which caused epidemics in Britain in 1831-1833, 1848-1849, 1853-1854 and in 1866, fits this trend. However one memorial has been found, and research into the event has provided us with insight into one family’s story.

Original documentation from the 1848-1849 cholera epidemic is sketchy, so newspaper reports are often the only way to find detail on the spread of the disease.

The first mention of Cholera in Northumberland comes in August 1849 with reports of cases in North Shields. By the 8th of September the Newcastle Guardian reports “Cholera in the Mining Districts – This fearful malady has at length found its way into the mining districts of New Hartley and Delaval. It appears that there have been upwards of one hundred and fifty cases of diarrhoea and cholera together in the immediate neighbourhood. Forty four have proved fatal up to the present time”. By the 15th September the Newcastle Guardian mentions that “At Wrekenton, Howdon, Walker, Seaton Delaval, North Shields and Barnard Castle it has been remarkably severe…Nor should the indispensable duties of mutual help and succour at this trying season be forgotten. Amid scenes of suffering and in the houses of the dying, Charity should walk fourth in all her genial influences; and whilst, with devout hearts and in the spirit of our holy religion, we look to Providence for the removal of the pestilence which in mercy or judgement He has visited our shores, let the wealthy and influential do good and communicate, as they have opportunity to their poorer neighbours and fellow-countrymen on whose families this heavy calamity may have fallen”.

An update from the Newcastle Courant on the 12th October reported “The Cholera at Seaton Delaval and Seghill, though considerably abated, has, since our last notice, been fatal to several families. In the night between the 2nd and 3rd [October] seventeen fell victims to it, and in one row of houses eleven corpses lay within a few yards of each other”.

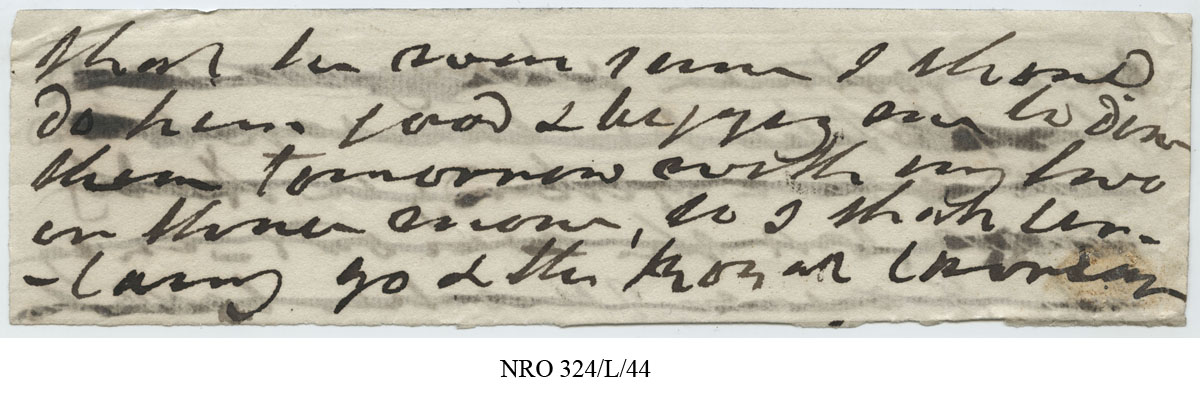

William Bell a miner from Seaton Delaval was one of those who succumbed, but was remembered in a printed silk epitaph, which now resides in Northumberland Archives. The silk states that he was”superinduced by his exertions to assist his fellow creatures during the attacks by this dreadful malady”. It is unclear who produced this silk or how many copies were made, but the two hands clasped together may indicate the item has a connection to a Trade Union.

In the publication, “Fynes’ History of the Northumberland and Durham Miners” published in 1873, states “The cholera having broke out at this time with great violence in the colliery districts, the attention of both employers and employed was turned towards the improvement of the sanitary condition of the villages, and union matters were laid aside for a time as great numbers of the workmen of the collieries were dying daily, struck down by the dire disease. Among those who fell victim was Mr William Bell, the secretary of the General Union whose death took place at Seaton Delaval.”

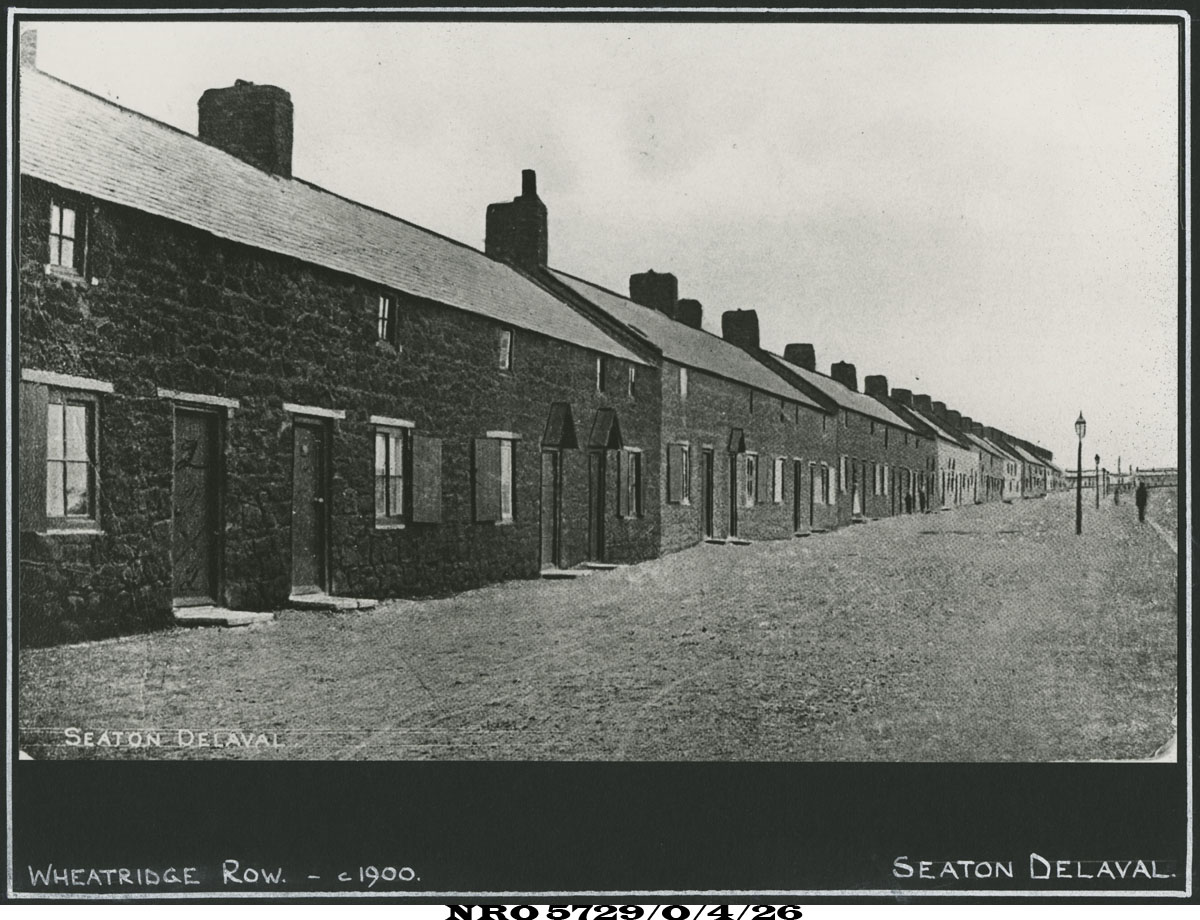

Seaton Delaval was at that time part of the Parish of Earsdon, William’s entry in the burial register has him aged 39 years old, and is buried the same day as his death, consistent with the directions for handling victims of contagious diseases, buried as soon as possible. A copy of his death certificate shows his death at Whitridge [Wheatridge] Row, Seaton Delaval, and the informant is Mable Bell, who was present at his death.

In the 1851 census for Seaton Delaval, Mable Bell, and her family are living at 4 Whitridge [Wheatridge] Row. Mable is a widow, and the assumption is she was William’s wife. Mable is aged 37 and is claiming Parish Relief. William the eldest son is aged 18 and is a Coal Miner, her son Christopher is 11 and is employed in the mines, daughter Mable is 8, and her youngest son Robert, is aged 3. Whitridge Row was one of the rows of tied houses for workers of the Seaton Delaval Coal Company. From this we can assume that William and Christopher are working for the Coal Company, at the time of the Census.

Reports of the disease in Seghill, Cowpen, Cramlington and other mining area throughout Northumberland seem to indicate that the disease in these areas were particularly virulent. An explanation was given by Dr John Snow, in his in his paper “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera” in 1855.

“The mining population of Great Britain have suffered more from cholera than persons in any other occupation; a circumstance which I believe can only be explained by the mode of communication of the malady. Pitmen are differently situated from every other class of workmen in many important particulars. There are no privies in the coal pits, or as I believe in other mines, the workmen stay so long in the mines that they are obliged to take a supply of food with them, which they eat invariably with unwashed hands and without knife and fork”. “It is very evident that when a pitman is attacked with cholera whilst at work, the disease has facilities for spreading among his fellow-labourers such as occurs in no other occupation. That the men are occasionally attacked whilst at work I know, from having seen them brought up from some of the coal-pits in Northumberland in the winter of 1831-1832 after having had, profuse discharges from the stomach and bowels, and when fast approaching to a state of collapse”.