On 3 January 1826 a 76 year old man named Joseph Hedley was brutally murdered in his cottage in the parish of Warden. Joseph’s throat and face were slashed and multiple stab wounds were inflicted upon his body. He was commonly known as Joe the Quilter due to his skill with needlework. He was a quilter by trade and travelled around the country seeking employment. Joe’s skills in quilting were celebrated, and his handiwork was known in various parts of England, Ireland, Scotland and America.

On the evening of the murder, Joe obtained a pitcher of milk, a pound of sugar, a sheep’s head and pluck (offal) from farmer’s wife Mrs Colbeck of Warwick Grange. At approximately 6pm William Herdman, a labourer living in Wall called in on Joe on his way home from work at the local paper mill and sat with him for a short time. Joe had a good fire going and was busy preparing some potatoes for his supper. Around 7pm Mrs Biggs, a female pedlar from Stamfordham knocked at the cottage to ask directions to Fourstones having missed the turning due to the excessive darkness of the night. Joe came to the door and gave her the necessary directions. Apart from the murderer(s), Mrs Biggs is said to be the last person to have seen him alive.

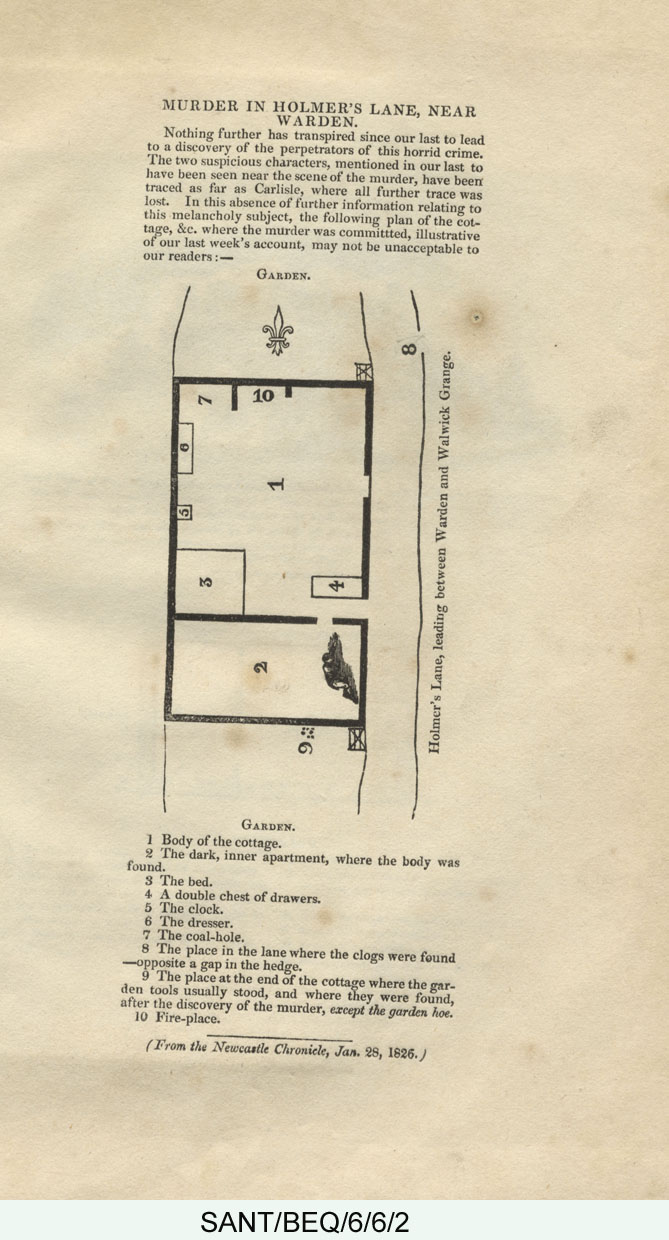

At approximately 8pm a Mr Smith of Haughton Castle rode past the cottage on his way home from Warden and all at the cottage was silent and dark. It is suspected that the deed took place between 7-8pm. Concern for Joe’s safety grew after his neighbours didn’t see the elderly man for a few days. It was reported that there appeared to be marks of blood in the snow outside the cottage and marks to indicate that a struggle had taken place. His neighbours found the cottage door locked and after knocking several times with no reply proceeded to break into the property. They were faced with a chilling sight as parts of the walls of the cottage were stained with blood and a quilt spread on a frame bore a distinct mark of a bloody handprint. The pitcher of milk, sheep’s head and pound of sugar which he had recently purchased were found lying on a table. A search of the house was conducted and nothing was found. An old outhouse which stored wood and coals was then searched and Joe’s body was discovered. Both cheeks were cut widely open with deep wounds. A garden hoe was found laid across his chest. A coal rake was also found with its shank bent. As two weapons were discovered it then raised a suspicion that there were 2 murderers. Joe was found with knife wounds on his hands so had obviously fought with the attacker(s).

The small cottage had been ransacked and bore evidence of a struggle. All of his boxes and drawers had been disturbed and it was believed that two silver tablespoons, four teaspoons and two old fashioned salt cellars of silver net-work had been stolen.The bed tester had been violently torn down and the face of the clock broken. Prints of 3 bloody fingers were distinctly visible on the chimney jamb . The plates on the dresser were also streaked with blood. Outside in the lane some clogs were found and a small piece of coat was discovered on a hedge.It was supposed that Joe had fought hard with the murderer(s) and had managed to escape about 100 yards from the cottage before he was caught. Judging by the marks in the snow it appeared that a struggle had taken place and then Joe had been overcome and dragged back and murdered. After this had taken place the cottage door had been locked on the outside and the key taken away.

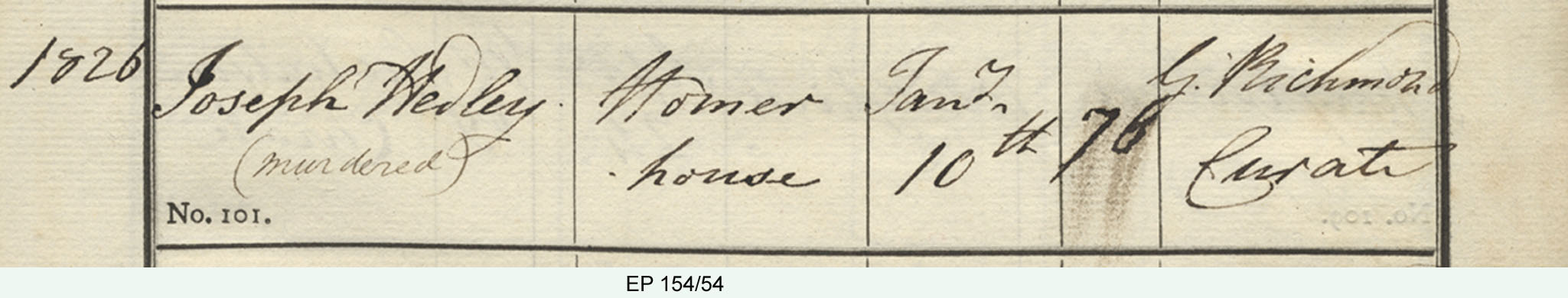

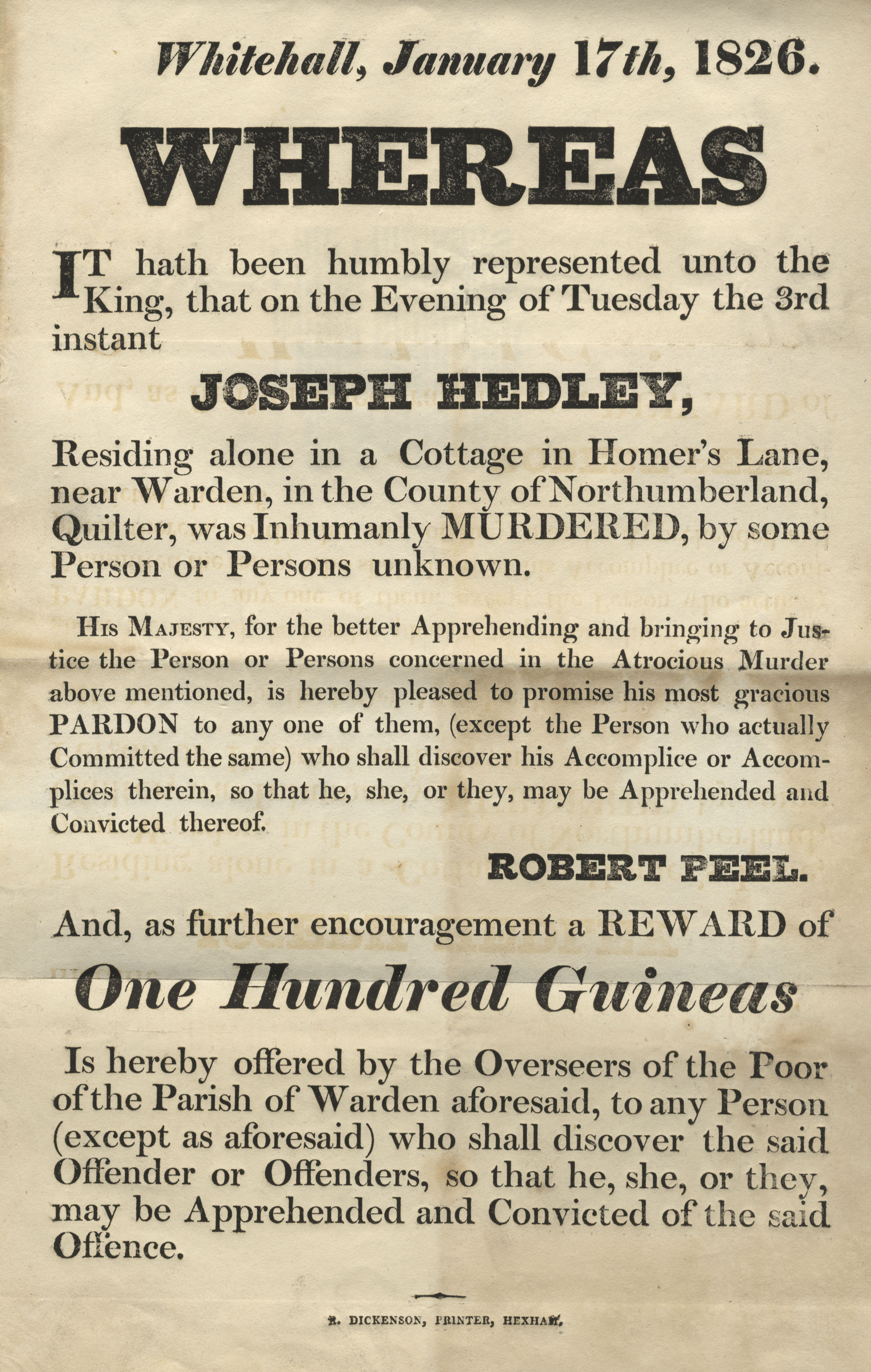

A one hundred guineas reward was offered to catch the perpetrator(s) of the atrocious murder . The reward was offered from the Overseers of the Poor of the parish of Warden on 17 January 1826. Home secretary Robert Peel offered his majesty’s full pardon to any accomplices who came forward with information (as long as they were not the actual murderer). A jury returned a verdict of wilful murder against some person or persons unknown. Although several people were arrested and questioned nobody was ever charged and sadly the murder of Joe the Quilter was never solved. Joe was buried in Warden churchyard on 10 January 1826. On his burial entry the word murdered can clearly be read underneath his name.

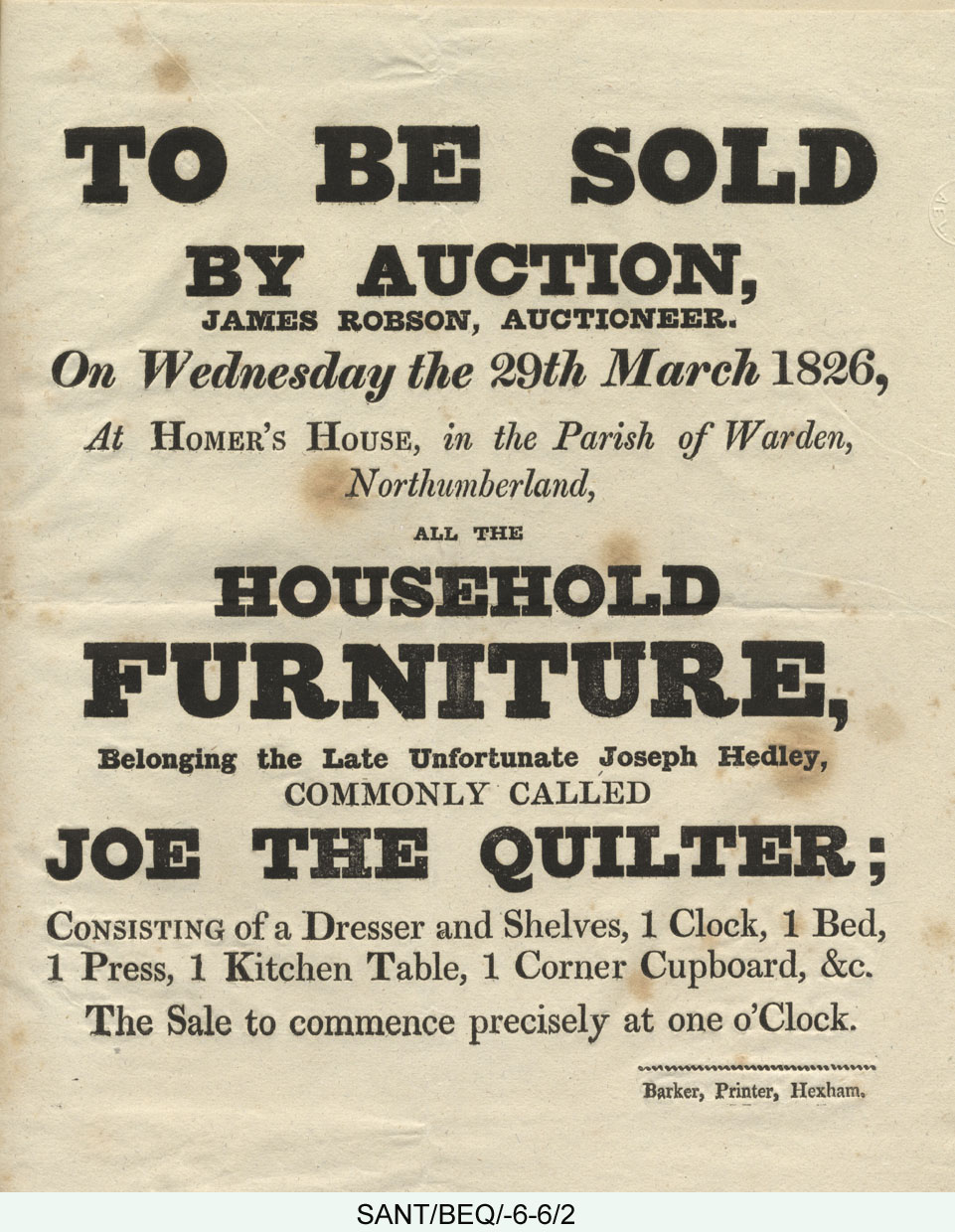

On Wednesday 29 March 1826, an auction was held to sell the household furniture belonging to the ‘late unfortunate Joseph Hedley, commonly called Joe The Quilter’.