This is the first in a series of blogs written by Peter Atkin, our placement student from Strathclyde University. Peter has been researching our manorial records and using our new online resources to learn about Northumbrian manors (https://northumberlandarchives.com/manorial-project/). Keep an eye on this blog for future posts on his findings!

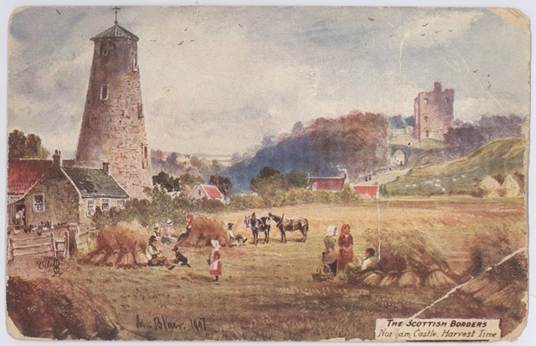

(A postcard of Norham Manor and Norham Castle (which was itself a manor) on the Scottish Borders)

When approaching the manorial documents housed by Northumberland Archive, it can at first seem quite daunting. Thousands of court rolls and as many of the similarly named, but historically very different call rolls, can keep you reading well past your bedtime without feeling like you’ve found anything of use at all. At least that’s how I felt, as a history student on a work placement with the Everyday life in a Northumberland Manor Project. But once the nerves settle and you begin to break these documents into chunks, it becomes a fascinating peephole into, well, everyday life in a Northumberland manor.

Tasked with producing a couple of blogs in my eight weeks placement and armed with two friendly and welcoming advisors, I spent the first two weeks simply sifting through the paperwork. The aim of this project is to highlight the vast amounts of manorial documents in Northumberland, which I can now attest to, as well as the uses which they can be put to. (Additionally, the Manorial Documents Register (MDR) also offers an index of all the manorial documents in England and Wales –https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/archives-sector/finding-records-in-discovery-and-other-databases/manorial-documents-register) From my early experiences, an important aspect of such documents is showing us the parts of history which are less often given the limelight. When one visits the magnificent Alnwick Castle, the lives of the Percy family and their role throughout British history are easy to learn and imagine. The roles of their servants and subjects, essentially the position most people found themselves in, is less accessible. Manorial documents can help us rectify this. They give us an interesting insight into the way in which authority was shared at a local level, with the perhaps unexpected revelation that many people were involved quite directly in the upkeep of their manorial customs. While those free tenants who were chosen as jurors for the courts were not the lowest class of medieval and early modern society, their role in the justice system is interesting nonetheless.

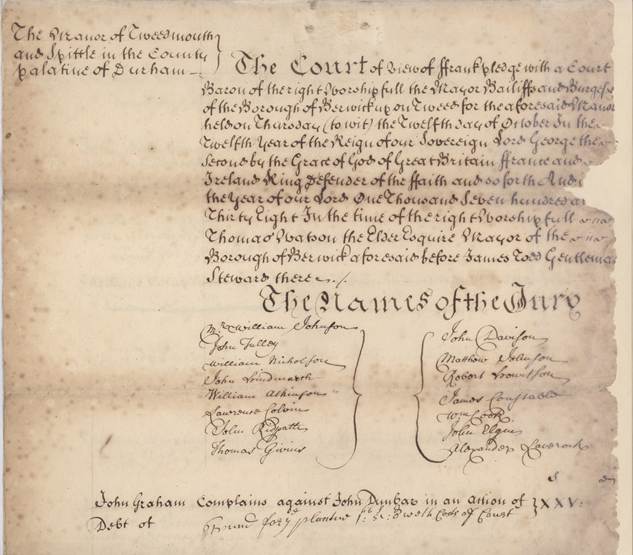

(Example of a manor court roll from Tweedmouth and Spittle, interestingly referred to as ‘in the county palatine of Durham’ despite the modern Tweedmouth being in Northumberland)

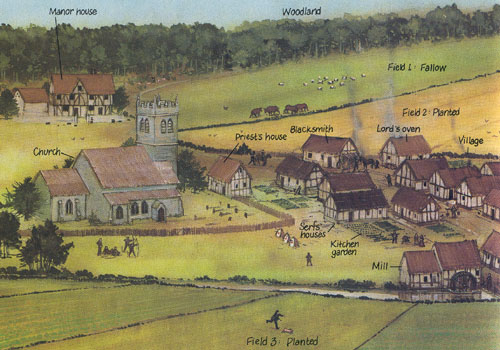

Manor court rolls, the transcription of events at the manorial courts which are held once or twice annually, describe the crimes and punishments which were occurring in different parts of Northumberland. It is perhaps important to note here that ‘manors’ didn’t necessarily have a house, and the term in fact refers to the area of land governed by a lord or lady. There are two main types of manorial court: the court leet and the court baron. The former dealt with large crimes and official appointments such as constables of the manor, while the latter was involved with more trivial cases often directly relating to local issues. For example, the Morpeth Court leet of 4th October 1779 makes reference to ‘permitting and suffering one sow and twelve Pigs The property of the said Robert Reed to go loose and at large upon the Kings highstreet within the said Borough.’ (SANT/BEQ/28/1/3/147-148 – Handwritten extracts from proceedings of Lord Carlisle’s Court Leet held at Morpeth, Northumberland, on 4 Oct 1779, nd. [c.1800]) At first, this seems a rather odd ‘crime’ which from the modern day can be seen as a funny historical tidbit. However, when looking through more manorial documents, we can see that this is actually an oft repeated wrongdoing and appears to be akin in commonality to the modern-day parking ticket. Indeed, there was a similar case in Newcastle recently, so perhaps history repeating itself refers to more than just the governmental mistakes of a given period! (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tyne-46794382)

(Morpeth Court leet of 4th October 1779, showing several persons ‘crimes’ of allowing pigs and sows to ‘go loose and at large’)

Additionally, call rolls list every person who lived within the bounds of the manor’s legal grounds. Manorial bounds can sometimes be identified using perambulations, documents which detail the specific borders and usually exist due to a disagreement by two landowners. This enables a Northumberland native, or the ancestors of one, to trace their family ties through history. This of course makes such documents incredibly useful to aspiring genealogists and those tracing a family tree, especially when used in conjunction to other sources such as Ancestry. (https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/8978/?redirectFor=db.aspx) They can also be used to trace more well-known figures, and potentially create links between places, people and events which are not already known about. This is especially interesting in the Northumberland manors proximity to the Scottish borders, where the cultural fluidity exemplified by the border reivers can be seen through the differing names and traditions compared to other English manors. This can also be seen at the Swinburne Charters Project, which focused on the documents of the Swinburne family. They were significant players in the Border Marches and such projects highlight how the manorial documents of places such as Norham Castle can offer a secondary insight into areas where other projects focus. (Swinburne Charters Project)

Some of the information gleaned from these manorial documents has been written about already, in the previous blogs on this website which can be found here (https://northumberlandarchives.com/manorial-documents-register-project/). After discussing the many uses and interesting facets of manorial documents (and ticking off a first blog which doesn’t technically use them very much), I’m excited to get stuck in and bring to light even more interesting historical findings for Northumberland’s ever-growing historiography. Hopefully you are too!

#heritagelotteryfund