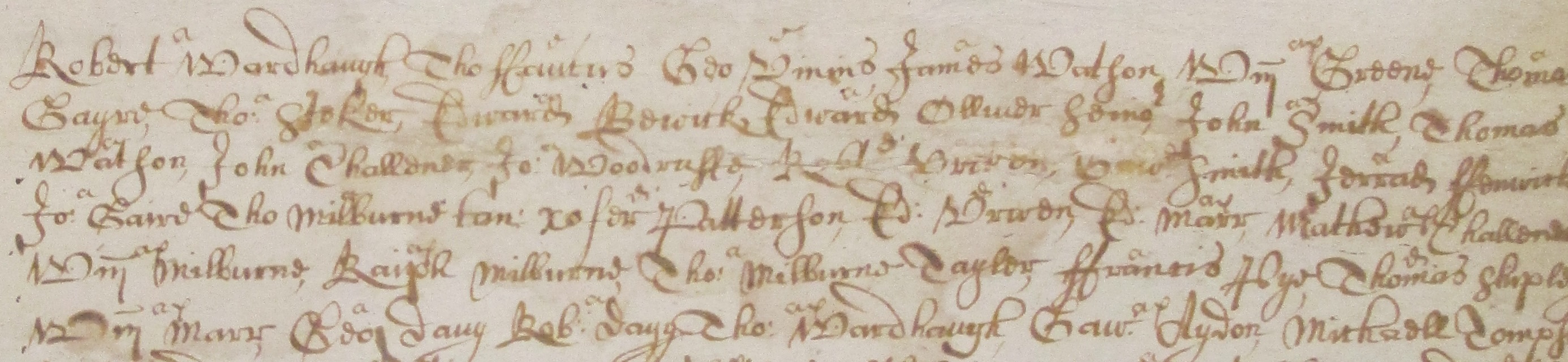

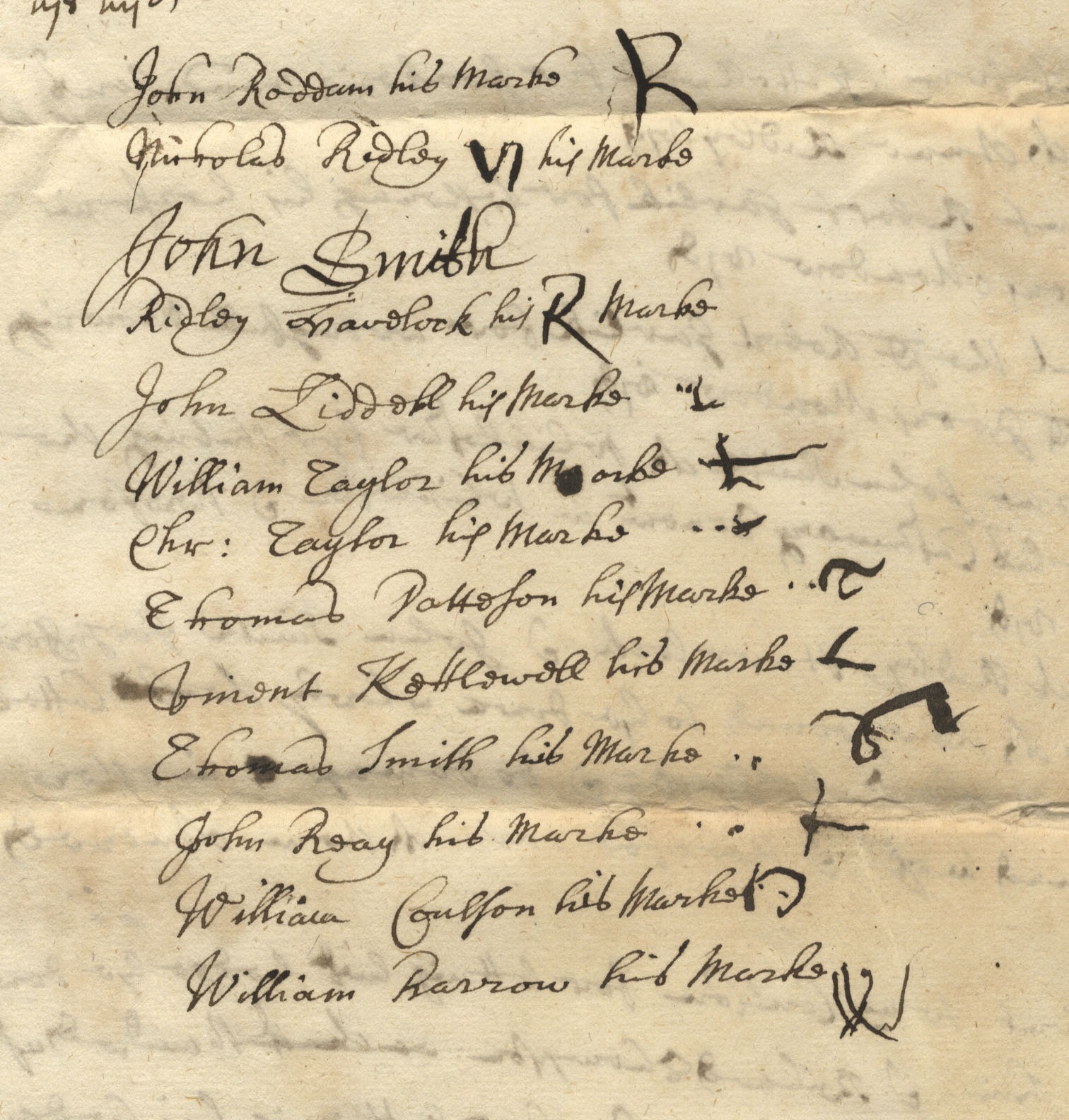

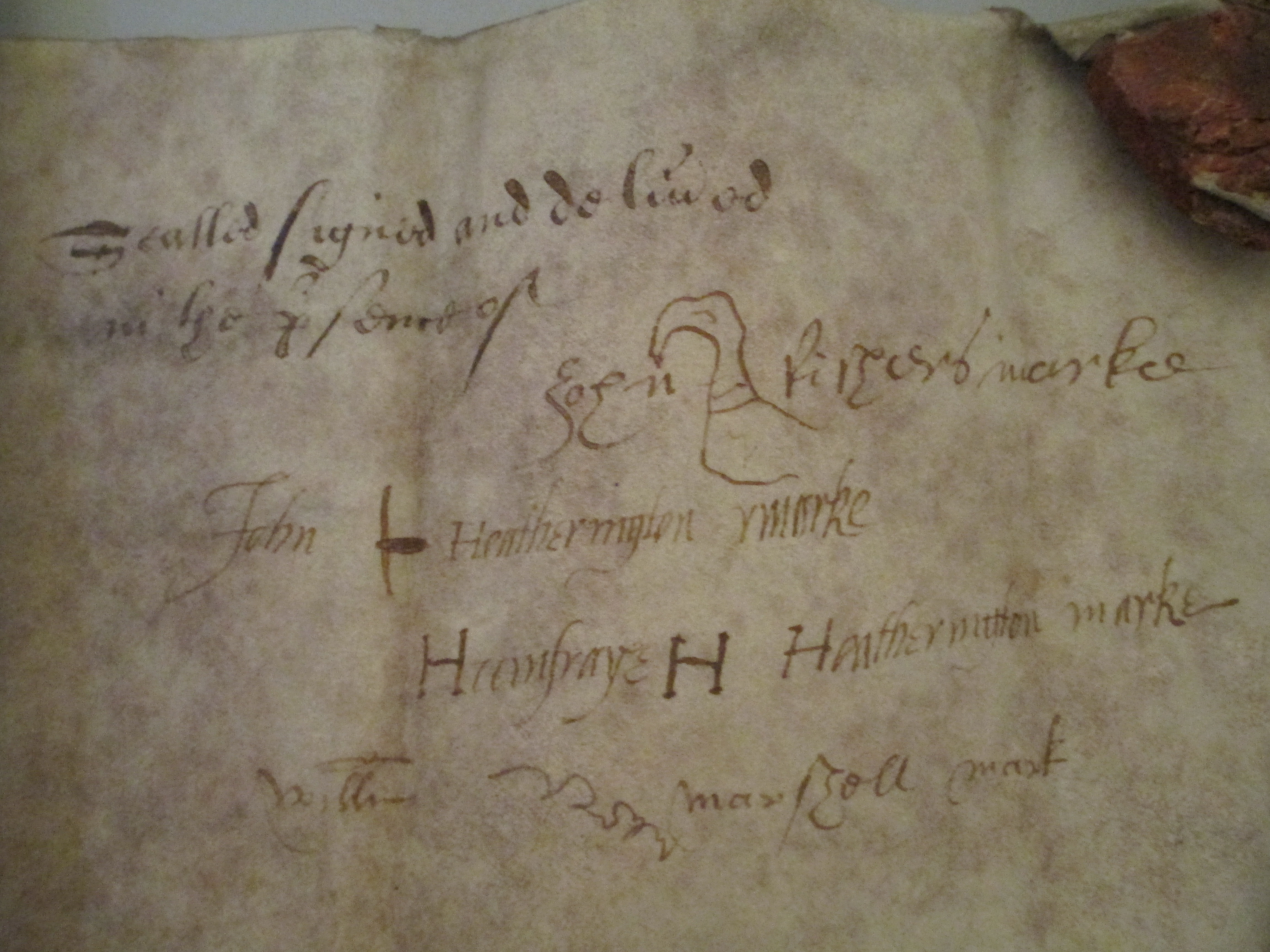

We can learn a lot about everyday life in the manor by looking at how it was organised. Using manorial documents we can identify individuals and look at what ‘customs’ (rules) they were required to live by, and how they bent or broke the rules that their manor imposed. You could be ‘presented’ before the manor to be ‘amerced’ (fined) for anything from large offences like cheating buyers at your market stall, to not having your chimney in correct repair or cutting back a tree hanging into a neighbour’s garden. Between different manors these rules could be strikingly different.

The customs were upheld by a number of different officials. A Bailiff or Reeve (paid and unpaid versions of the same post) took on the day to day running of the manor. He might be assisted by a barleyman (‘byelaw man’ in charge of upholding the bye laws of the manor), Pinder or pounder (in charge of impounding livestock), lookers (into a particular area, such as fencelooker who examined boundaries and fences), among other roles depending on the needs of the manor. We find evidence of these officials in the manorial documents.

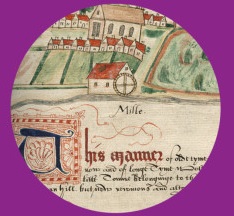

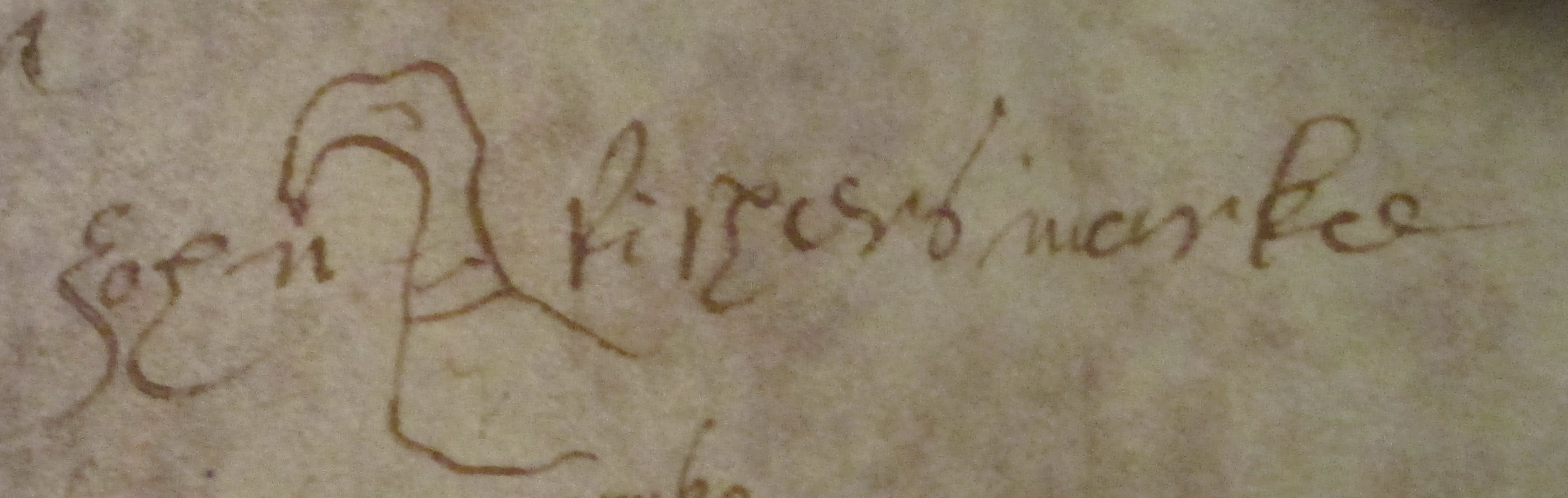

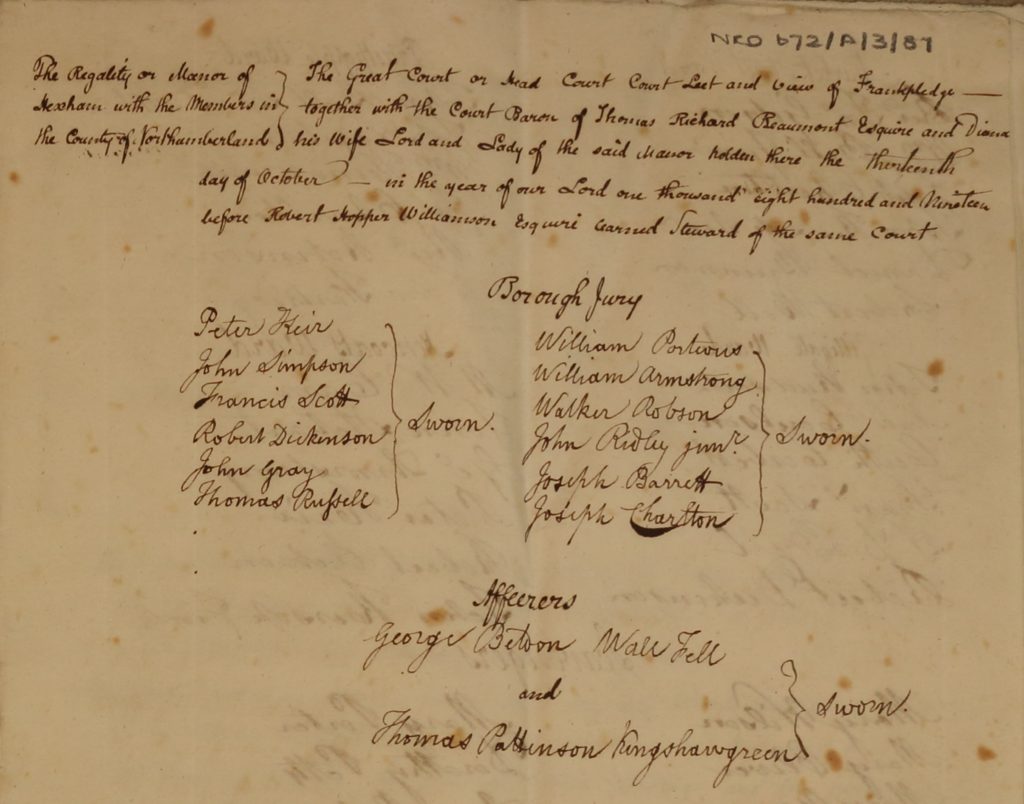

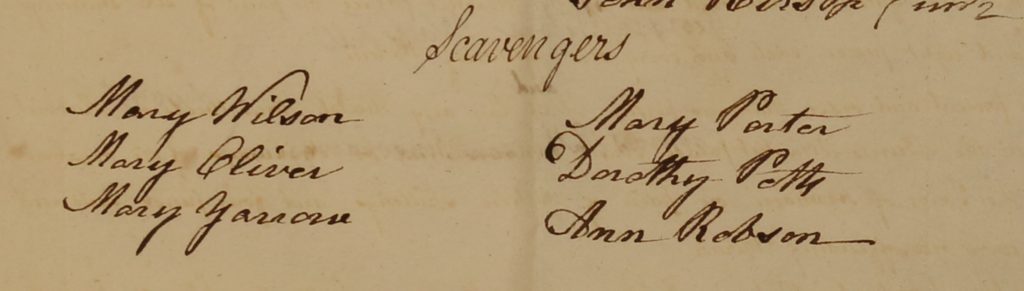

To show how customs worked we will take Hexham manor as an example. In Hexham we have an excellent series of what is known as the Borough Jury books (often spelt ‘burrow books’) from the seventeeth to nineteenth century which give ‘presentments’ (judgements of cases) jurored by a group of the townsmen known as the four and twenty. These books list other roles like the common keepers, market keepers, waits, affeerors, and scavengers. Affeerors were appointed from among the tenants to ensure amercements (fines) were kept fair. Waits were watchmen, often required to sound the hour. The (often female) scavengers swept the market and maintained street gutters in the town, fighting against the piles of rubbish (also ashes, thatch, weeds, gravel, bark and stones) Hexham’s townspeople were presented for leaving.

Other roles can also be found:

Read moreIt’s our custom – day to day life in the manorial documents