In order to determine which places in Northumberland are actually manors and which aren’t we gather supporting historical evidence, and we write this up into a Manor Authority file. Every potential candidate will have one of these by the end of the project, even if it only contains a short sentence to confirm that it isn’t a manor. We use the documents discussed in previous posts and local history sources approved by The National Archives, such as the Northumberland County Histories, Hodgson’s Northumberland, Raine’s North Durham (which covers Bedlingtonshire, Norhamshire and Islandshire), and trade directories. We scour the histories for references to the manor, its description, owners and how it was passed through different hands and families. Our aim is to provide a complete account of the manor, with no gaps in ownership. However as being lord of the manor brought an income and social position these can also be fascinating stories of murder, abduction, forced marriage, theft of property and estates being squandered by profligate heirs. It isn’t always a simple case of an owner being ‘to the manor born’, you could become lord of the manor through marriage, purchase, or be rewarded with one for service to the monarch. We hope to relate some of the tales we have uncovered in future blog posts. Below we have given the example of the Manor Authority file we compiled for Ford.

FORD

Ford Parish

Alias: Foord

Geographical extent: Includes the townships of Ford, Kimmerston; Catfordlaw; Broomrigg; Flodden; Crookham; Ford; Ford Westfield ; Gatherick

Honour/Lordship details: Barony of Muschamp

Ownership: The manor of Ford was originally part of the Barony of Muschamp. By the late 13th century it was owned by the Heron family and remained in their possession until the mid-16th century. During this time it was passed mainly from father to son, with William Heron owning it by 1520. By 1557, the ownership of the manor was disputed between the Heron and Carr families because of the marriage of Thomas Carr to Elizabeth, daughter of Sir William Heron. The disagreement was brought to a head in 1558 with the murder of Thomas Carr. The manor then passed to the Carr family and remained with them until the early 18th century. In the 1660s, the manor was in the possession of three sisters of Thomas Carr – Margaret, married to Arthur Babington; Elizabeth, married to Francis Blake; and Susan, married to Thomas Winkles. By the early 1700s, Francis Blake had bought out the other sisters to become sole owner of the manor. He died in 1717 and the manor then passed to his grandson Francis Delaval, the child of Mary Blake and Edward Delaval, on the understanding that he assumed the surname Blake – becoming Francis Blake Delaval. The manor remained with the Delaval family until 1822 when it passed on the death of Susan Delaval to her granddaughter, Susan, Marchioness of Waterford. It remained with the Waterford family during the remainder of the 19th century. In 1907 the Ford Estate and manor were sold to Lord Joicey and have remained with Joicey family since this date.

Courts:

View of Frankpledge with Court Baron – referred to in the first extant court roll – 1658

Sources:

NRO 1216/A7/8 – Ford Manor Court Rolls

Northumberland County History, Vol. XI, pp.341-410

Kelly, E.R, (1914), Kelly’s Directory of Northumberland

Anyone can request to see original documents like the manor court rolls in the Northumberland Archives searchroom, see our website below for how to visit.

http://www.experiencewoodhorn.com/collections/

You can also find many of the history books and directories we use online, using the following links.

Hodgson, Mackenzie and the County Histories can be found at:

www.archive.org

Scott’s History of Berwick can be accessed using:

http://www.electricscotland.com/

Trade directories are available through the University of Leicester’s special collections:

http://leicester.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p16445coll4/hd/

For pictures, maps and other digitised images for Ford, many of which come from our archives, try Northumberland Communities: http://communities.northumberland.gov.uk/Ford.htm

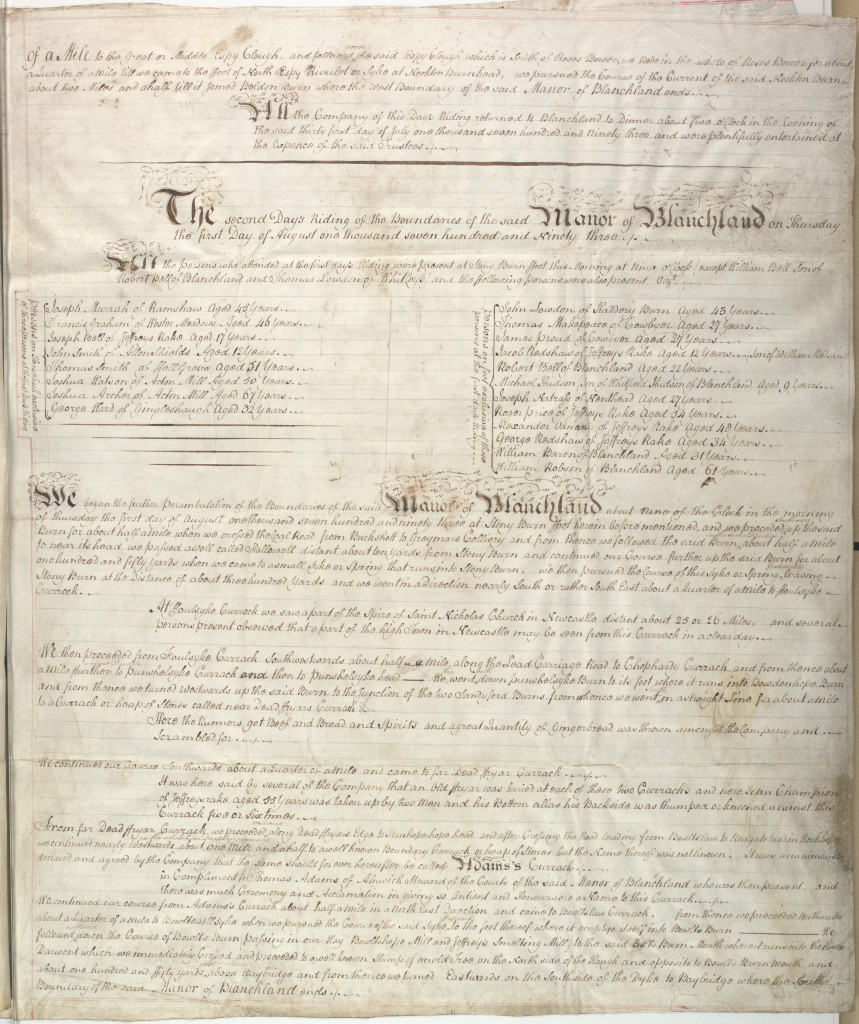

Boundary roll – Description of the manorial boundary, though not a full perambulation.

Boundary roll – Description of the manorial boundary, though not a full perambulation.

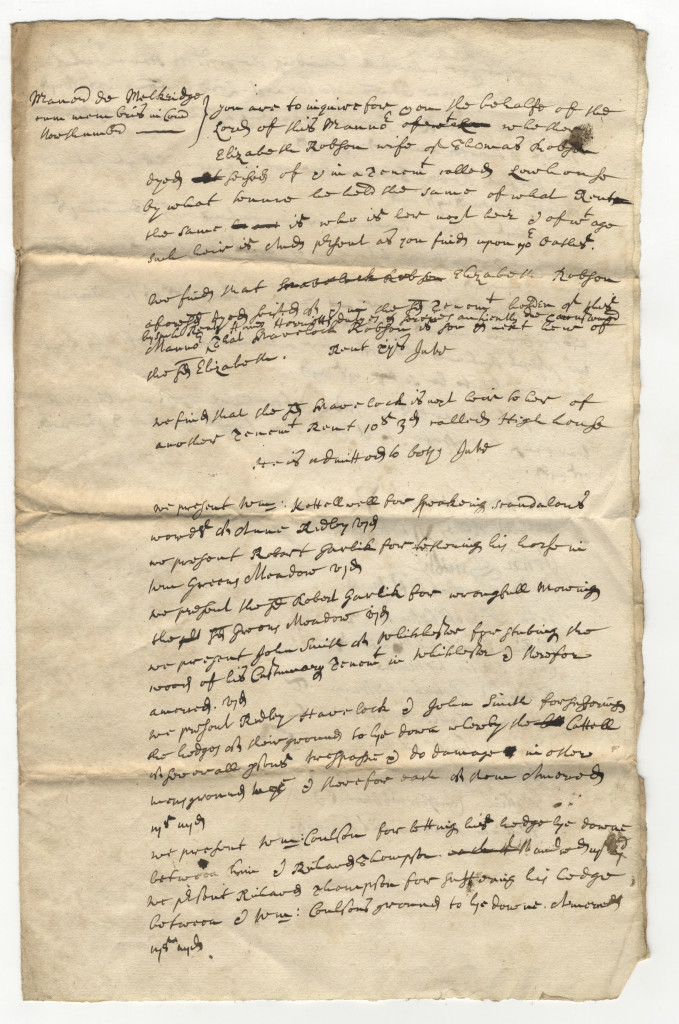

Presentments – lists of the matters to be dealt with by the court, such as disagreements between tenants or disobeying the manor customs, often drawn up beforehand by the jury. They might often be included in the court roll. ZBL 2/13/21 has some interesting examples including those brought before the court for offences such as ‘speaking scandalous words’ of someone or ‘wrongful mowing’ of someone else’s meadow.

Presentments – lists of the matters to be dealt with by the court, such as disagreements between tenants or disobeying the manor customs, often drawn up beforehand by the jury. They might often be included in the court roll. ZBL 2/13/21 has some interesting examples including those brought before the court for offences such as ‘speaking scandalous words’ of someone or ‘wrongful mowing’ of someone else’s meadow.