During the First World War Stannington Sanatorium continued to run, but there is no doubt the lives of those there were affected by it. We can gain an excellent insight into that time through the lives of a family closely connected with it, the Atkin family. Here we will look at the Philipson Farm Colony manager John Atkin’s wartime farm, and will follow this with another post that will look at his son Robert’s war and a project exploring the men of Stannington village in WWI, and unveil sanatorium nurse Hilda Currie’s (Robert’s wife) album of photographs.

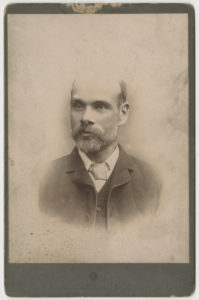

John Atkin

John was born on the 28th March 1858 in Rothbury. On the 1861 census we find him living with parents Robert and Joanna in Corbridge. Robert was a Blacksmith from Corbridge, and Joanna was from Rothbury. John had a sister, Isabella, and his 11-year-old uncle Adam lived with the family. This would be a big and busy household as Robert and Joanna would go on to have another six daughters and five sons, and apprentices and visitors also shown on the census. John followed his father into the Blacksmithing trade, and married Margaret. The couple are found on the 1881 census living in Stargate, near Ryton, with John working as a colliery Blacksmith. Their son Robert was born there in 1882, though the family had moved to Scotswood-on-Tyne by the birth of daughter Minnie two years later.

However the family were divided on the 1891 census. John was living at Newburn Hall, Lemington, the sole occupant of a house, and was working as a Blacksmith. Margaret is harder to locate, but it is likely she was a patient in the Royal Infirmary in Newcastle at the time. During her stay there Robert and Minnie had gone to stay with their grandparents Robert and Joanna in Corbridge, the house still busy with aunts and uncles Joanna, Minnie, Matthew, James and Jane, and three visitors.

John became the farmer at Whitehouse Farm in 1900, and on the 1901 census Margaret, Robert and Minnie are all present at Whitehouse, with Robert employed as a farmer’s son. However John was not there. He was boarding with the Nylander family at Newburn Hall, and working as a Blacksmith. Perhaps this was a transition, or he was supporting the family while the farm was still being set up. Five years later the Philipson Farm Colony was established by the PCHA, and John was asked to remain and train the boys in agricultural skills. John grew crops, raised livestock, and he and Minnie kept hundreds of chickens, with the eggs sold to the sanatorium. They also supplied the sanatorium with milk, and sewerage from the sanatorium was used as manure on the fields.

John gave a talk to the Newcastle branch of the Rotary Club, published as an article in the August 1918 volume of the Rotary Wheel magazine, in which he described his endeavour to maximise yield from the farm. At the end of the First World War this was vital as the country became affected by food shortages. John argued these were caused by the farmers’ preference for producing only sheep or cattle, though he felt “they could hardly be blamed for adopting a system that pays them best”. A reliance on imported wheat meant:

“The doctrine of the cheap loaf has carried the day, and we are now paying for it in millions – the neglect of this most important industry has brought us almost within measureable distance of defeat.”

He then described how he had taken on and run Whitehouse farm. The first year’s profits were entirely used in rates, taxes etc., perhaps suggesting why John had found work Blacksmithing again. He turned over more fields to hay, and made a 100% profit on poultry farming. The fields, once drained, produced better crops, and in eight years the yearly value of the farm’s produce rose from £400 to £1200. This was with the help of the boys from the farm colony, and they took the ideas learned from John with them into their adult careers, and even overseas.

John felt that “Well-cultivated land is a national asset, and at any time like the present is equal in value to many Dreadnoughts”. He felt the war would revolutionise farming, and though it did not bring many ‘back to the land’ as he suggested it did bring about greater use of machinery: “In many farm operations the motor will supersede the horse”. However his most important argument for farming to help the war effort lay in the diversity of stock and crops he had introduced in his own farm:

“We scour the world for eggs that might be produced at home … Organisation, co-operation and modern appliances will, I am convinced, make the farming of the future an industry such as it has never been in the past in our country”.

This seems to have worked, as the National Farmers’ Union statistics show that only 50% of eggs and 19% of wheat consumed in Britain originated here in 1914, compared to 87% and 83% in 2013.

The family moved to The Birches in Tranwell Woods, and John built the family a home there in 1910, named White House after the farm. The family lived there for many years. Robert’s granddaughter recalls her father’s memories of following John around his different pursuits, such as beekeeping (never wearing a hat) and growing apples for shows. He also won trophies for shooting with the Hexham Volunteers. His huge greenhouse in which he grew tomatoes and chrysanthemums was destroyed during the Second World War.

We will continue the story with Robert, Helen and Helen’s photograph album in a future post.