In September 2014, I heard that Northumberland Archives needed volunteers to delve into the experience of the First World War. As an amateur archaeologist I am interested in history and thought this would be a fascinating project to get involved in, and as I do freelance work, I would be able to do it when I was not working.

I went along to the training days which were very interesting. I was already familiar with the family history section of the archives at Woodhorn as we have been researching my husband’s family, the Lindsays of Alnwick. On completion of the training days we were each given a project to undertake and mine was to transcribe the diary of an ‘unknown’ First World War soldier which had been handed in to the Archives.

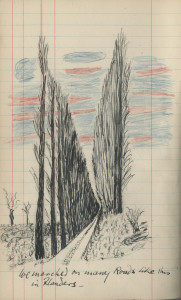

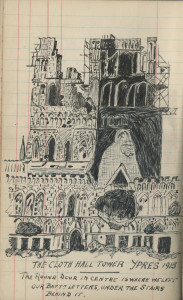

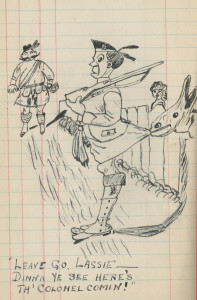

I found this to be utterly fascinating. The diary is very well written, full of humorous stories, heart breaking and vivid accounts of the writer’s experience of death and war, drawings, and even a theatrical programme! I actually found it a privilege to be one of very few people to read this diary since it was written. Some of his accounts moved me to tears and brought the whole experience of the war very close to me, and as a mother, I couldn’t help but be mindful that each account of a soldier dying such an awful and lonely death was somebody’s son. I was privilege to details of their deaths that their mothers probably never knew. The author reveals a loyalty to his country, respect for superiors and acceptance of ‘doing one’s duty’ which is rare today.

I became so interested in this man’s stories that I really wanted to find out who he was. He gave some clues along the way, such as the fact that he knew a lot about sheep and farming. A German steamer had run aground near Cheswick Burn ‘to the south of our land’, and his brother had been in command of the coastguard at Berwick. From this it was clear that he had some connection with farming in an area I am very familiar with in Northumberland, and I thought that it would be easy using the internet to find out the name of his brother. I had no luck and emailed the RNLI and other organisations such as the website of the London Scottish, his regiment, but had no replies. I took my husband along to have a look at the diary and we read on further. The words jumped out from the page when we read that his ‘dear brother Cecil’ was killed whilst in command of the cruiser H.M.S. Bayano on 12th March 1915. This was an enormous clue. We went home and spent the evening in pursuit of our soldier and found him.

Using Google we found that his brother was called Henry Cecil Carr who was 43 when he went down with his ship. From this, I had his birth year so I then looked at census records and found Cecil in the 1881 census when he was 8, along with his father John Carr who was a Merchant and Justice of the Peace, five sisters and 4 brothers, Reginald E, George, Hubert and John E. Which one was our soldier? The census showed that they had all been born in Gosforth and were living at Roseworth Cottage, Coxlodge. I then found Cecil in the 1911 census living in Rochester, Kent, with his occupation as ‘Royal Navy Commander’ so I knew we had the right family.

With these clues, I googled and found that Reginald E was the coastguard, so that narrowed our unknown soldier down to George, Hubert or John E. Remembering that our soldier had mentioned ‘our land’, I decided to look at Kelly’s Trade Directory for 1914 for Berwick, and found one John Evelyn Carr on page 21 as Manager of Scremerston Coal Company, coal owners and merchants, brick and tile manufacturers and farmers. I strongly suspected we had our man! (It was midnight by this time).

I was about to do some double checking to make sure this was our soldier and decided just to put his name into Google to see if there was any more information on the net about him. I got a shock! Up popped an entry for Northumberland Archives about one John Evelyn Carr who had written 4 war diaries, and who had had a special study on him done by Emily Meritt in 2014. I read her work about the soldier and recognised from the information about him that my soldier and hers were one and the same person! There was even a photo of him, which I found fascinating I could now put a face to the person behind the diary. His words had also featured in a book called ‘Tommy at War 1914-18, the Soldiers’ own Stories’ by John Sadler, and I found another photograph and information that he had been a sheep breeder on ‘Historypin’. The mystery was solved but I was a tiny bit disappointed that my soldier had already been known about, and his diary wasn’t unique. He seems to have been a prolific writer! We have still to find out if my diary is part of the four already known about, or separate.

I found out that he had been married in 1900 at St Andrew’s, Newcastle to one Gertrude Isabella Moncriff Blair (obviously not a scullery maid). He had worked after the war as Managing Director of the Scremerston Coal Company and lived at Heathery Tops Scremerston and Spittal, where he died in 1958. I have recently found out that there is a farmer whose surname is Carr who farms at Scremerston today and am minded to get in touch with him to see if he is a relative. It would be interesting to know how the diary came to be in the Archives and not cherished by John Carr’s family as a precious heirloom.

I feel that I know this man. I think he descends from The Carrs of Etal who once owned Barmoor Castle where our family have a holiday home today. It is odd that he was born and brought up about half a mile from where I live, and that he lived and worked in an area I know well and love. I even know the road where he lived in Spittal. It was meant to be that I got to transcribe his diary, and I hope I can do justice to his bravery and brilliant storytelling, so that other people can experience the immediacy, humour and sorrow that I have felt while transcribing it.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Carole McKenzie for supplying this article for our Northumberland At War Project.

Northumberland At War

First World War Letters from the Front – The Christmas Truce.

A letter from loved ones fighting a brutal war in a foreign country provided some relief for the families left at home; at least it was proof that they were still alive at the time of writing.

Below are some examples published in local newspapers – there was a thirst for knowledge of the war; publishing these letters gave comfort, not only the immediate family, but also to those with relatives in the same regiment or battalion or area of battle.

Letters published early in 1915 revealed the incredible story of the Christmas Truce.

LETTERS FROM THE FRONT

NORTH COUNTRY SOLDIERS’ EXPERIENCES

WITH THE “FIGHTING FIFTH”

Private Patrick Igo who is serving with the Northumberland Fusiliers, at the Front, in a letter to his mother, who resides at 48, St James’ Square Gateshead, states: “Just a line to let you know I am still going strong. The condition of life out here is rough, and so is the weather, but it the old tale, ‘Stick it Jerry’. There are some fine places in ruins: churches, Catholic convents and homesteads; the handiwork of ‘Jimmy the Germans’. My opinion is that they are getting beaten every day. We are getting plenty of ‘baccy’ and cigarettes from England so you need not worry about smokes.

We have had some casualties since I have been with the regiment, both killed and wounded.

Writing to his brother on December 28, Private Igo says:

There is some hard fighting around the district, where the old ‘Fighting-Fifth’ is located and we are here for our share, when wanted. We came out of action on Christmas Eve for a day or two’s rest, after having occupied some German trenches, which one or two of the kilted regiments had taken from the enemy in the middle of November. I will not forget it for a few Christmas Eves to come, if spared. We lost a few while holding the trenches. The Germans were no more than 40 yards entrenched in front of us; we waited eagerly at dusk for our relief. We all expected a peppering that night.

H.A.C IN THE TRENCHES

In a letter written on Boxing Day to Mr Noble of the Broomhill Collieries, Mr Oswald Blunden an Officer of the Honourable Artillery Corps states:

“Your parcel of chocs’ reached me in the firing line; the contents and the good wishes enclosed have already cheered my heart. We are now having a spell of six days in the trenches and the weather has decided to be seasonable. Christmas day was cold and dry and a glorious change from what we have had. All today it has been snowing hard. It’s wee bit ‘parky’ now and then, especially about four or five in the morning. It’s nice to get up, but taking it all round, the cold knocks the mud into a cocked hat.

At the moment I have got a few hours watch on and have to post sentries and see that they are the alert, every now and then. One must not sleep during this time and so in between the rounds I am knocking a few arrears.

Perhaps you may have heard how we spent our Christmas Day. It was the most extraordinary thing possible – mixing-up and holding long talks with the enemy, out in the open and not a shot fired on either side. I got a jolly good German helmet, which I am going to try and send home when we get back to the billets.

There are two of us in my dugout in the trench and the way I have to twist myself in Knots all the time is a sight for the Gods. Now is the time I would like to be 2ft 6in and not 6ft 2in.

“A MERRY CHRISTMAS”

Corporal Robert Renton of the Seaforth Highlanders in a letter to Mr and Mrs Renton of Coldstream tells of the way in which Christmas Day was spent at the Front. He writes:

“I never thought we would spend Christmas the way we did. We were in the trenches on Christmas day. On Christmas Eve the Germans in front of us started singing what appeared to be hymns. We were shouting for encores (their trenches are only about 150 yards in front of us), and they kept the singing up all night. On Christmas Day some of them started to shout across to us, to come over for a drink.

It started with one or two going over half-way and meeting the Germans between the two lines of trenches; then it got that there was a big crowd of German and British, all standing together shaking hands and wishing each other a merry Christmas. They were giving us cigars and cheroots to exchange for cigarettes and some of them had bottles of whisky. They seemed a decent crowd that was in front of us.

They were all fairly well dressed and the majority of them could speak broken English. Some of them could speak it as well as myself. They said they were not going to fire for three days. They kept their word too: there was no rifle fire for two days after Christmas. There were two dead Frenchmen between our lines. We could never get out to bury them ‘till that day. The Germans helped us to dig the grave. One of their officers held a service over the graves. It was a sight worth seeing and one not easily forgotten; both Germans and British paying respect to the French dead.

The following was published in the Newcastle Journal Jan 1st 1915:

More stories of Christmas celebrations.

“HOB-NOBBING” WITH THE ENEMY

How an unofficial armistice was observed between German and British troops on Christmas Day is related in a letter written by a local officer at the Front to Mr and Mrs Taylor of Braemar, Victoria Avenue, Forest Hall. He writes:

“The Germans looked upon the day as a holiday and never fired a shot, except for a few shells in the early morning to wish us the compliments of the season, after which there was perfect peace and we could hear the Germans singing in their trenches. Later on in the afternoon my attention was called to a large group of men standing up half-way between our trenches and the enemy’s on the right of my trench, so I went out with my Sergeant-Major to investigate and actually found a large party of Germans and our people hob-nobbing together, although an armistice was strictly against regulations, the men had taken it upon their own hands.

I went forward and asked in German what it was all about and if they had an officer there – I was taken up to their officer who offered me a cigar. I talked with them for a short time then both sides returned to their trenches. It was the strangest sight I have ever seen. The officer and I saluted each other gravely, shook hands then went back to shoot at each other. He gave me two cigars one of which I smoked and the other I sent home as a souvenir. If only I had had a camera, I could have sent you an interesting picture. I do not know if this unofficial armistice was general in other parts of the line or not.

“A QUEER TIME”

Writing from the Front to fiends at Jarrow under date December 26 a soldier thus describes his Christmas Day on the battlefield:

“Things have been remarkably quiet during Christmas, and the infantry went so far as to come out of their trenches. On Christmas Eve an infantryman went into the German trenches at midnight and made himself comfortable. They gave him drinks and smokes and a German soldier accompanied him half-way back to his own trench.

While in the German trenches a British soldier made an arrangement that a truce of 24 hours would be called between his company and the Germans. On Christmas Day soldiers on both sides left the trenches and exchanged greetings, cigars, cigarettes and so on. Where possible the men conversed with each other and exchanged names and addresses”.

The writer proceeds, “I have heard this happened all along the British line, excepting where the Prussians were opposed to it. I had occasion to go down to the trenches and I tried to talk to the Germans. I had my photo taken with them and I wish I could get the proof. Now today it is different. When we were at peace with them yesterday, we were at war today and the guns are roaring as usual and the rifles are being fired. It is a queer time right enough.”

“A GUID NEW YEAR”

Corporal T.B. Watson now at the front with the 8th Royal Scots (Territorials) in a postcard to his cousin Mr R Smith of the Shipley Street Baths, Newcastle says:

“I had a merry Christmas in spite of those boys 300 yards over the way. We came in here to relieve the Englishmen for Christmas. They in turn will let us have New Year out. It is decent of General _____ to do this as it suits both regiments just fine.

On Christmas Day the greatest thing out took place here – Somehow or other a friendly feeling got up between the Germans and us, so we both left our trenches unarmed and exchanged greetings about 300 yards apart. We were all standing in the open for about 2 hours, waving to each other and shouting and not one shot was fired from either side. This took place in the forenoon. After dinner we were firing and dodging as hard as ever; one could hardly believe that such a thing had taken place.

We are getting hard frost today (December 27) and it makes us busy to try and keep warm but the trenches are cleaner so we are better off that way. Wishing you a ‘Guid New Year’.”

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Derek Holcroft in supplying this article for the Northumberland At War Project.

For Bravery

On the night of Monday 26th March 1917, the Ashington Coal Company hosted the first of four presentations to reward employees who had won great distinction in the First World War. On this occasion twenty-three men were honoured, for their bravery and their gallantry in their respective theatres of war, three of the men had been killed in the line of duty.

The presentation took the form of a silver cup, individually engraved with the recipient’s name and a few words of appreciation from the Ashington Coal Company. This ceremony was later repeated a further three times in February 1918, July 1919 and finally in February 1922, with 91 silver bowls, presented to the men or to their families. The men had gained the following distinctions: two men were awarded a Military Medal and Distinguished Conduct Medal; twelve men were recipients of the Distinguished Conduct Medal; one man received a Military Medal and bar; one man received a Serbian Gold medal, and seventy-five men were recipients of the Military Medal.

In September 2015 at the beginning of the ‘Weeping Window’ poppy exhibition we were approached by a lady who asked if we would be interested in a rose bowl for the collection. The family belief was that her grandfather was presented with this bowl for saving the life of the son of an official from the Ashington Coal Company during the First World War, but as he never spoke of it, they could not be certain.

On the night of 6th February 1918, 132670 Sapper James Smith of the 254/7 Tunnelling Corps, Royal Engineers, was presented with his silver bowl at the Harmonic Hall in Ashington. The newspaper report in the Morpeth Herald published two days later on the 8th gave this account of the reason behind his reward “Sapper James Smith, Tunnelling Coy., Strong’s Buildings, Choppington, M.M. For saving three men’s lives in a mine explosion in France”. The bowl was presented in appreciation of his bravery, in saving the men’s lives.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Derek Holcroft whose painstaking research found reference to these presentations taking place and to Deborah Moffat for supplying this article for our Northumberland At War Project.