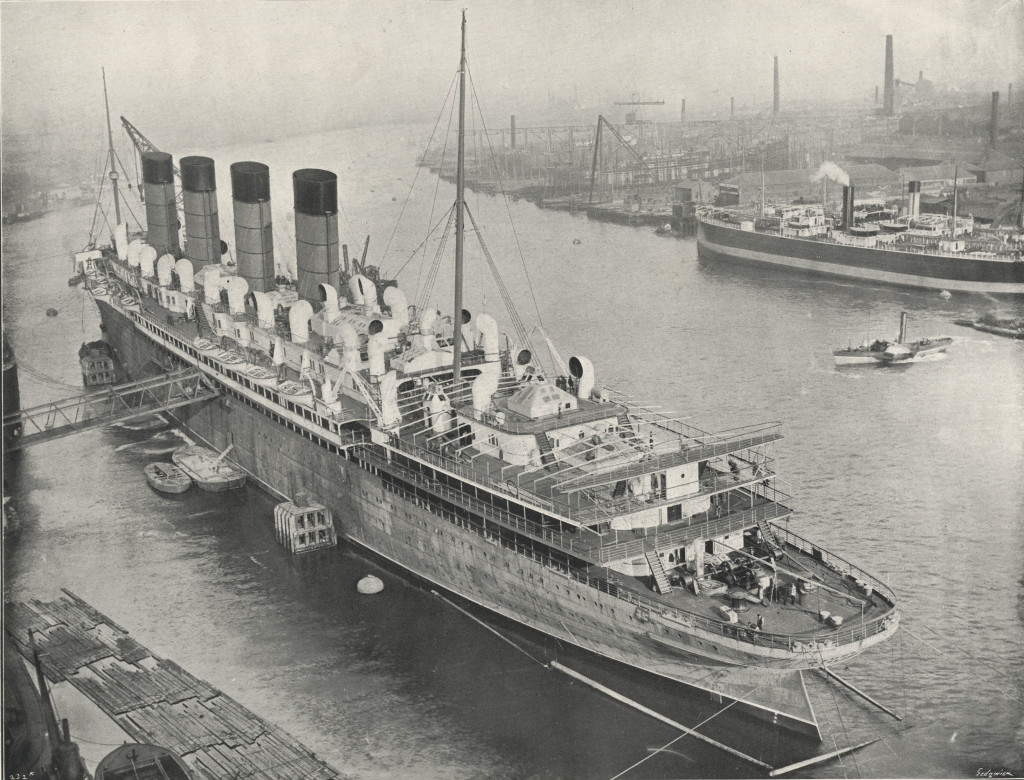

Amongst the many collections held by Northumberland Archives are some family papers of the Taylor Family of Tynemouth. Within this uncatalogued collection we have located a large folio book published by the offices of “Engineering” of Bedford Street, Stand, London in 1907 on the Cunard Atlantic Liner “Mauretania” which was constructed by Messrs Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Limited of Wallsend on Tyne (ref ZTA 4/1).

The Wallsend shipyard where the Mauretania was built dates back to 1872. Mr C.S. Swan was the principle partner, but soon after his death in 1878 Mr G. B. Hunter became head of the firm. The firm became a limited liability in 1895 and in 1903 amalgamated with Messrs Wigham Richardson and Co. The combined companies then had a river frontage of some 4000ft and covered an area of 78 acres. The yard was located about three miles east of Newcastle upon Tyne on the north bank of the River Tyne at a point where there is a bend so that little difficulty is involved in launching large vessels.

When she was built in 1906 the Mauretania was the world’s largest ship. This record was held until The Olympic was built in 1911. The Mauretania consisted of nine decks, seven of which were above the load water-line. During construction they used a product known as Corticine [A material for carpeting or floor covering, made of ground cork and India rubber] instead of wood to save on weight for the deck covering.

Her capacity was 2165 passengers in total consisting of the following 563 First Class, 464 Second Class, 1138 Third Class and 802 crew.

This book comprehensively records dimensions and furniture in all the rooms for first, second and third class passengers. We have extracted some information from the book to provide a flavour of what she must have been like.

“The boat deck extends over the greater part of the centre of the ship and contains some of the finest en -suite rooms. At the forward end you could find the First Class Library, Grand Entrance Hall, First Class Lounge, Music Room and First Class Smoking Room.

The Library extends across the deck house and is 33ft long by 56ft. The Lounge is 80ft long and 56ft wide. The Veranda Café is the same as the Lusitania’s and is sure to prove a popular resort.

The Regal Suites comprise a drawing room, dining room, two bedrooms, bathroom and private corridor. They are all decorated in the Adams style. The carpets, throughout the suite are green. The rooms are supplied with statuary marble chimney pieces and electric radiators. Both bedrooms are Georgian in character with carved mouldings and the wall panels are covered in silk. They are finished in white with mahogany furniture

The Nursery was decorated by Messrs J. Robson & Sons of Newcastle it is in mahogany, enamelled white and the panels have a series of quaint paintings of the well-known nursery rhyme ‘Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie.’ The dining tables and chairs are of a suitable height for little passengers. There is accommodation for four stewardesses and two matrons.”

Her official trails extended over four days terminating on 7th November 1906. There for 4 trails where he vessel steamed at an average speed of 26.04 knots. The trails took place sailing to and from Corswall Point Light, Wigtownshire, Scotland to Longship Lighthouse, Cornwall a distance of 304 nautical miles each way. This course was used because the length could be travelled in about 12 hours so that tidal influences on the north and south runs would balance each other. Her first run south was affected by adverse weather. Over four trails the vessel steamed at an average speed of 26.04 knots.

Her first trans-Atlantic voyage took place on 16th November 1907 when she departed Liverpool for New York, under the command of Captain John Pritchard. She continued her Atlantic voyages until the outbreak of the First World War when she was requisitioned by the British Government to become an armed merchant cruiser, but due to her size and excessive fuel consumption she was deemed unsuitable and reverted back to her Atlantic trips, but due to lack of passengers she was laid up until May 1915.

After the sinking of the Lusitania she was used by the British Government as a troopship for the transportation of troops during the Gallipoli campaign. As a troopship she received what was known as dazzle camouflage, this was a form of abstract colouring applied to confuse the enemy. Later she became a hospital ship and was repainted white with large red crosses. Later in the war she was requisitioned by the Canadian Government and used to transport Canadian troops from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool and once America entered the war in 1917 used to transport American troops to the UK.

She returned to her civilian life after the First World War in 1919, until she was withdrawn from service in 1934, being ‘deemed surplus to requirements.’

This post was prepared by Paul Ternent, Northumberland At War Volunteer Manager.