On the 29th December 1854, at about 9 o’clock in the evening, Mr John Moffat threw down and leveled a “certain rail” belonging to the Alnwick Abbey toll gate situated on the Alnwick and Eglingham turnpike road. Documents from the Dickson, Archer and Thorp collection allow us to follow this case through the courts, and can help us to unpick Moffat’s localised actions and national motives. It is thought these documents were kept as Mr William Dickson, a generational partner in the firm, had been heavily involved in the establishment and maintenance of Alnwick’s turnpike road.

Turnpike Roads and Trusts

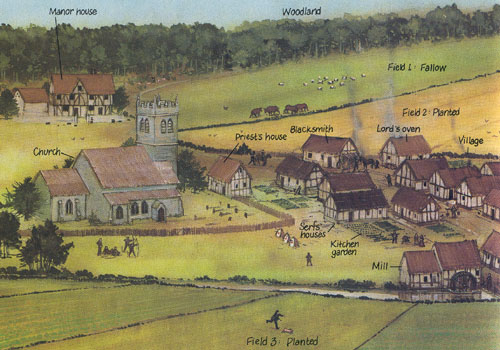

The establishment of turnpike roads had been first encouraged by central government during the eighteenth century. To use these roads travellers were required to pay a set toll at the turnpike gate. The term “turnpike” derived from the spiked barriers placed on these toll booth gates. The levied toll would then be re-invested into the road’s maintenance and repair. This system of re-investment created a better road network; allowing for the more efficient movement of goods and the furtherance of industry.

Turnpike roads were managed by “turnpike trusts” consisting of local business owners and industrialists. To create a turnpike road the trust would request permission from central government. Once permission had been granted the trust was free to set a toll. They would then retain control over the road for 21 years, although this time could be extended by Parliament. By the passing of the last turnpike act in 1836 there had been 942 acts for new turnpike trusts across England and Wales, and turnpike roads covered roughly ⅕ of the total road network.

A series of toll booth adverts placed in the Newcastle Courant referring to the letting of turnpike toll gates and master positions. The gates referred to here would have been similar to the one Moffat leveled in 1854. REF: NRO 11343/B/DAT

The turnpike toll gate Moffat damaged had been established after a meeting between the Alnwick turnpike trustees in 1826. This was evidenced in court by Joseph Archer, whom produced the trustees’ minute book obtained from the office of their clerk A. Lambert Esq. Archer also produced various other pieces of evidence to prove the gate’s legality. This included a minute book entry referring to the letting of the Toll Master position to William Patterson and a copy of the Newcastle Courant containing the original letting advert.

Queen vs Moffat

The aforementioned evidence was used against Moffat at the Northumberland Adjoined Epiphany Sessions, held on the 22nd July 1855, where Moffat faced two accusations. The first being that he had leveled the toll gate in a “malicious manner,” and the second that his actions had prevented subsequent travellers from paying the due toll.

William Patterson had only been the Alnwick gate toll master since the 13th May 1854. Prior to this he had been living in the area with his wife Margaret and their four young children.

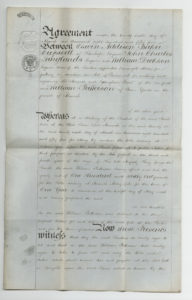

Agreement to let the Alnwick turnpike toll to William Patterson. Also note Mr Dickson’s name included amongst the trustees, further evidence of his close involvement with the case. REF: NRO 11343/B/DAT.

Yet, despite being in the position only a short while, he admitted to the court that he did;

“not collect the tolls myself generally but I authorise my daughter Alice Patterson to do so in my absence and she had principally collected them since the tenth of June last.”

Alice was his eldest child, born around 1838, and the principle witness to Moffat’s damage. She testified that Moffat had rode into Alnwick with his brother Arthur and refused to pay the designated toll. He had told Alice she could tell her father to put him before the magistrates, but that the toll was unlawful and he therefore would not pay. Upon trying to leave Alnwick hours later the Moffat brothers found themselves locked within the city. Mr Patterson still hadn’t returned to the toll gate, and Alice refused to grant them exit without receiving the outstanding payments. The men refused once more and, as also witnessed by Miss Isabella Williamson, John got down from his horse and began to level the offending gate in the following manner:

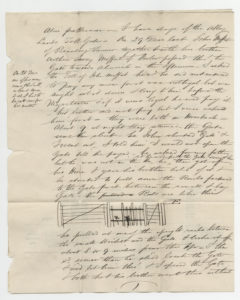

“He then started to pull down the rails between the Gate and the Gate House. These rails were in line with the gate across the road and are to prevent any one passing without paying the toll. He broke a piece off the top of one of the rails and she (Alice) told him she would rather open the gate then watch him break it.”

Alice Patterson’s witness statement, accompanied by a small sketch of the turnpike gate. REF: NRO 11343/B/DAT.

Turnpike Riots

Mr Moffat’s defence, both at the time of the act and in court, had been that the “the gate was not legal.” This opinion fed into a larger national feeling, with over a century of toll riots having occurred across England and Wales targeted at the swift spread of turnpike gates.

During the 1720s and 1730s some inhabitants of Kingswood near Bristol resented the payment of newly set tolls, which they perceived as being unfair on coal traffic. They subsequently tore down the newly erected turnpike gates and eventually won the exemption of coal traffic in the area. But, with local farmers yet to be pacified, the Bristol riots continued across the latter half of the century. In 1753 riots began in the West Riding of Yorkshire, again because coal traffic had been forced to pay heavy toll duties which had a ripple effect upon the area’s textile production.

Yet, with respect to the timing of Moffat’s stand, the most recent turnpike riots had been the “Rebecca and her Daughters” movement in rural Wales. Between 1839 and 1843 men disguised themselves as women to pull down toll gates in their areas. They referred to themselves as Rebecca’s daughters in reference to a biblical passage about the need to “possess the gates of those who hate them.”

Hence, although industrialists and entrepreneurs may have viewed turnpike gates and trusts as a positive development, small holders or independent artisans saw them as an unnecessary blight on their income and business dealings. Occupational information about the Moffat brothers places them into this latter category, with John being named as a Beanley-based farmer in Alice’s testimony and Arthur Moffat having worked as a farmer in Eglingham on the Turnpike road. It is therefore likely that John would have empathised with the concerns of his national counterparts regarding the heavy payment of tolls, and this allows us a potential insight into Moffat’s belief that the gate was unlawful.

Punishment

Irrespective of Moffat’s motivation or inspiration he was found guilty before the court of committing a misdemeanour. Whilst the collection’s documents do not specify the court’s punishment there is a letter between Mr Dickson and a clerk working for the Duke of Northumberland which ambiguously suggests an out-of-court agreement was drawn up between Moffat and the trust.

Ultimately the event does not seem to have inspired further opposition against the toll gate and, as the Duke of Northumberland assured Mr Dickson in correspondence, there was no intention to close the toll booth in the wake of the court case and the turnpike road operated as usual.