An undated document found within the Dickson, Archer and Thorp collection tells the heart-wrenching story of John Walker and his young family. The Walkers were forcible ejected from their home in Warkworth due to their Scottish ancestry. The document details the terrible treatment of the Walker family by their Warkworth neighbours, and its author requests legal advice from the Dickson, Archer and Thorp firm regarding how to proceed with what has become a complex and sensitive issue involving three warring parishes.

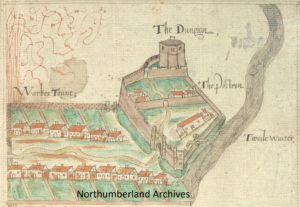

The case probably occurred in the mid-1800s. John Walker, his wife and four children had been residing in a room in Warkworth for two years. John earned a living as a shoemaker, working for different masters. Due to a prolonged period of illness John was unable to work for a time, and his family received temporary poor relief from Warkworth’s overseers of the poor.

The Walkers were of Scottish origin and had been granted legal status to settle in England a few years prior. The people of Warkworth, reflecting nineteenth-century anti-Scottish sentiment, were “devious” and had been conspiring to push the Walkers out of their village. They saw an opportunity with John’s illness and forced his shoemaker master to stop giving him work once he recovered. They then bullied his landlord into seizing his rooms and articles of furniture.

Despite such cruel and unfair treatment the Walker family refused to leave the parish; probably because they had no place to go. The overseers then took legal action to achieve their aims. They escorted the family to be examined by two local Justices of the Peace over their legal right to settle in England. During the examination John explained that, whilst he had been born in Inverkeithing in the “shire of Peebles”, he had been granted legal status to stay and work in England. However, the Justices sided with the scheming overseers and signed a warrant to forcibly send the Walkers to the parish of Peebles. The family were to be accompanied to Scotland by Warkworth’s overseers.

Once in Scotland the family were delivered to the clerk of the Kirk Sessions for the parish of Inverkeithing. A meeting was called by Kirk members and they decided to refuse settlement, even though John had been born in the parish, as he had also resided in a place called Penicuik for many years. The Walkers were then forced to travel to Penicuik, Scotland under instructions to settle there instead. But the Penicuik overseers also refused entry and sent the family back to Warkworth.

The family were left with no other option than to return to Northumberland. They were “fatigued and exhausted with so long a journey in an open cart in severe winter weather, they remained a few days in a lodging house in Alnwick to refresh themselves.” When they finally arrived in Warkworth John demanded he be treated justly and granted entry. He also insisted on having his previous lodgings returned to him. The overseers complained loudly about the Walkers return and John went to the house of the resident magistrate to plead his case. But the magistrate was one of the Justices who had signed the original warrant and the Walkers were once again denied settlement in the parish.

The family were forced to make the eight mile trip back to Alnwick in awful winter weather. This final journey was almost fatal to their youngest child. John went to the Alnwick overseers of the poor and made a complaint against the conduct of the Warkworth parish. The Justices of Alnwick demanded the Warkworth overseers came and answered these astonishing claims of cruelty and mismanagement. Whilst the overseers obeyed the summons and traveled to Alnwick, they still refused to grant the family access to their old lodgings. The Warkworth overseers claimed they had obeyed the law by delivering “paupers” to their parish of origin, and maintained that they were not responsible for what had occurred after they had issued the warrant. They also told the Alnwick overseers to “do their worst,” but warned that they would stand by their original decision.

Exasperated, the Alnwick overseers requested legal advice from the Dickson, Archer and Thorp firm. The firm returned a final and damning opinion. They called the conduct of the Warkworth overseers “very disgraceful” but warned it would be difficult to punish them “as they deserve.” They suggested obtaining an indictment against the Warkworth overseers on grounds of conspiracy (based upon their initial scheming behaviour). Due to the absence of dates it is difficult to find any further record of John and his family, although it is hoped the Warkworth overseers received a suitable punishment.

We would like to thank the volunteer who kindly listed the documents relating to this case.