In this post we’re going to explore the progression of pulmonary tuberculosis in one particular patient from Stannington Sanatorium in order to gain an insight into some of the common approaches to the treatment of the disease at this time.

Patient 95/1947 was admitted to Stannington Sanatorium on 4th September 1947 at the age of 12. After having begun to feel ill earlier in the year she was examined at the local clinic and sent for x-ray whereupon it was determined that she should be admitted to the sanatorium for treatment. Prior to admission she had been living with her mother, step-father, two younger brothers and one younger sister in a 3 roomed house in Cockermouth which had no inside water or inside toilet. The only family history of TB had been her father who had died from the disease when she was still a baby. On admission she had no cough but a very poor appetite and was losing weight, weighing only 4st 0lbs 6oz. There were no other physical symptoms or abnormalities reported.

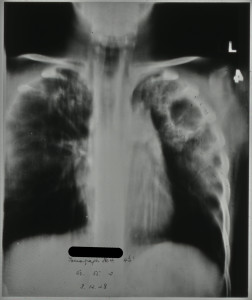

The report on her first x-ray taken 4 days after admission reads:

“Tuberculous infiltration of both upper lobes with a large cavity in the mid-zone & a smaller one at the left apex. There are several small calcified foci in the right upper lobe.”

Continuing reports over the next 4 months describe great improvement on the right side with the cavity in the right mid-zone no longer being visible. However, the condition of the left side continues to deteriorate with a report 7 months after admission stating that the “cavity in the left upper lobe is now very much larger 1 ½” in diameter.”

[HOSP/STAN/7/1/2/1444/19 – tomograph showing large cavity in left upper lobe, Dec 1948]

During her stay a series of different treatments were attempted to reduce the cavities. Two months after admission in November 1947 her doctor initially observed that it was “doubtful if a satisfactory collapse could be obtained. No treatment recommended. Outlook very poor.” Nevertheless, two months later in January an artificial pneumothorax was attempted but without success.

Artificial pneumothoraxes were performed on patients with the intention of resting the affected lung and hopefully collapsing the cavities at the same time whilst preventing any further spread as a collapsed lung was less likely to spread bacilli. The procedure had been shown to effect a marked improvement in the size of tuberculous cavities for some patients but could at the same time be a dangerous procedure with a risk of air embolisms, pleural shock, sepsis, emphysema and effusion.

[HOSP/STAN/9/1/1, artificial pneumothorax treatment being performed in Stannington]

Three months later, after observing the growth of the cavity in the left upper lobe, a phrenic crush followed by a pneumoperitoneum was recommended and she was transferred to Shotley Bridge Hospital soon after for the procedures to be performed. By crushing the left phrenic nerve, situated in the neck, they would be able to disable the left diaphragm thus forcing the muscle to relax and lift up, with the idea being that this would then rest the lower part of the lung. A pneumoperitoneum was often performed in conjunction with the phrenic crush and involved inserting air into the abdominal peritoneal cavity forcing the diaphragm up.

Unfortunately after the patient was transferred to Shotley Bridge Hospital for the above procedures she never returned to Stannington and so we do not have any later case notes to follow up the result of her treatment. However, some later correspondence does tell us that she was moved to Poole Sanatorium from where she was eventually discharged in May 1950.

The surgical procedures described here sound very drastic from a modern perspective but were a common approach in the pre-antibiotic era. With no effective drug treatments surgical approaches such as these were at the forefront of tuberculosis treatment and looking through the files of Stannington Sanatorium it is clear that many of their young patients recovered, or at least showed significant improvements, and went on to live normal lives.