William Beresford Orde Lisle was born into upper Northumbrian society on June 25th 1886 at 50 Jermyn Street, London. His parents, Jane Lucinda (an Australian lady) and Bertram Lisle (a barrister-at-law from Alnwick), were well connected and their financial standing allowed William to lead a life of luxury and entertainment.

Childhood

William grew up between the family home in Jermyn Street, London and their country seat at Brainshaugh House, Northumberland. One can still visit William’s birthplace in Jermyn Street; just around the corner from St James’ Palace. References to the street first appeared in rate books for St Martin’s parish in 1667. In these documents the street was referred to as ‘Jarman Street’ in reference to the Earl of St. Alban’s, a man called Henry Jermyn, whose trustees had originally leased the land from the crown in the latter 1600s.

Number 50, the place of William’s birth, is now a high-end fashion shop called BOGGI MILANO. During the nineteenth century Jermyn Street was filled with hotels including the notable Waterloo Hotel and Cox Hotel (the latter of which was the Lisle’s contemporary neighbours, occupying numbers 53 – 55). An influx of visitors to the area was therefore facilitated by the wide choice in accommodation, and this allowed the street to develop both financially and culturally. In the 1890s Messrs J. Lyons and Company decided to capitalise upon the up-and-coming area by expanding their successful teashop in Piccadilly to new premises in Jermyn Street. A museum was even established in the street, thus encouraging a cultural surge. The museum was first established in the 1840s to house a collection of geological specimens although, by the time of William’s birth in 1886, the collection had begun to outgrow its site and the building was eventually demolished in the early 1900s. Numbers 57 and 58 of Jermyn street, although altered significantly over time, were used extensively as workshops. Whilst number 80 had been some form of public house since 1783.

The Jermyn Street familiar to the Lisle’s would therefore have been a bustling centre full of people and trade. Moreover, its close proximity to the Royal buildings would have made it a nucleus for political activity and the perfect base for an up-and-coming barrister such as Bertram. In comparison, the Lisle’s home in Brainshaugh House offered a completely different pace of life; in a rural setting with greater space. This second property is now a grade II listed building close to a picturesque ruined priory.

Family Connections

Bertram, William’s father, was a well-established member of Northumberland society. In the 1889 electoral poll for his local area he was registered as being one of only two “Ownership Voters, Parliamentary.” He also sat on the Board of Governors for the Alnwick Infirmary and chaired the Alnwick Ragged School Board. In 1882 he was involved in a terrible cart accident along with another gentleman (most likely his father or brother). During the accident the two passengers, along with their driver, were thrown from their vehicle when the horse became spooked. The out-of-control the horse and cart then trampled a passing regiment of the 3rd Northumberland Fusiliers; leaving two seriously injured.

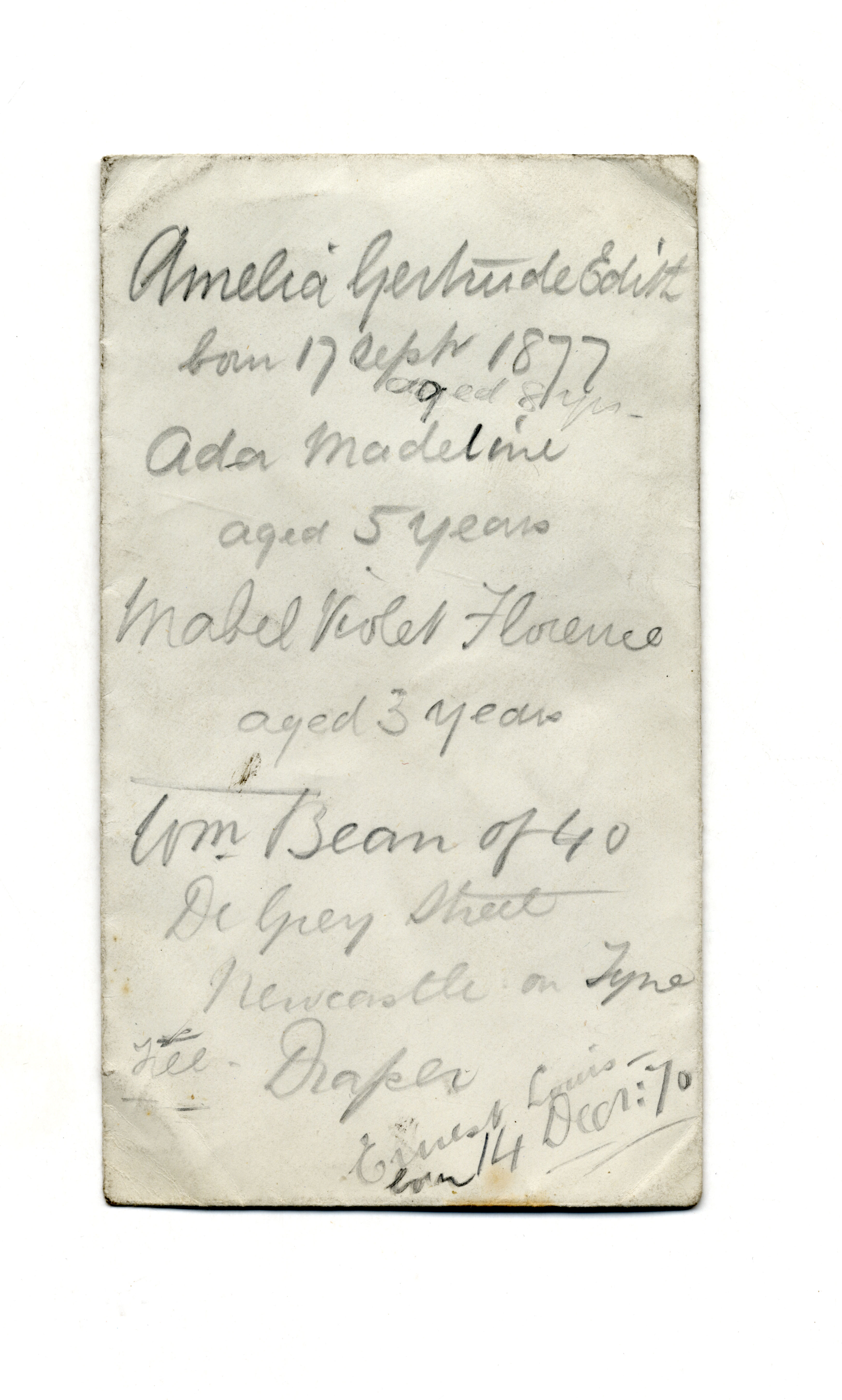

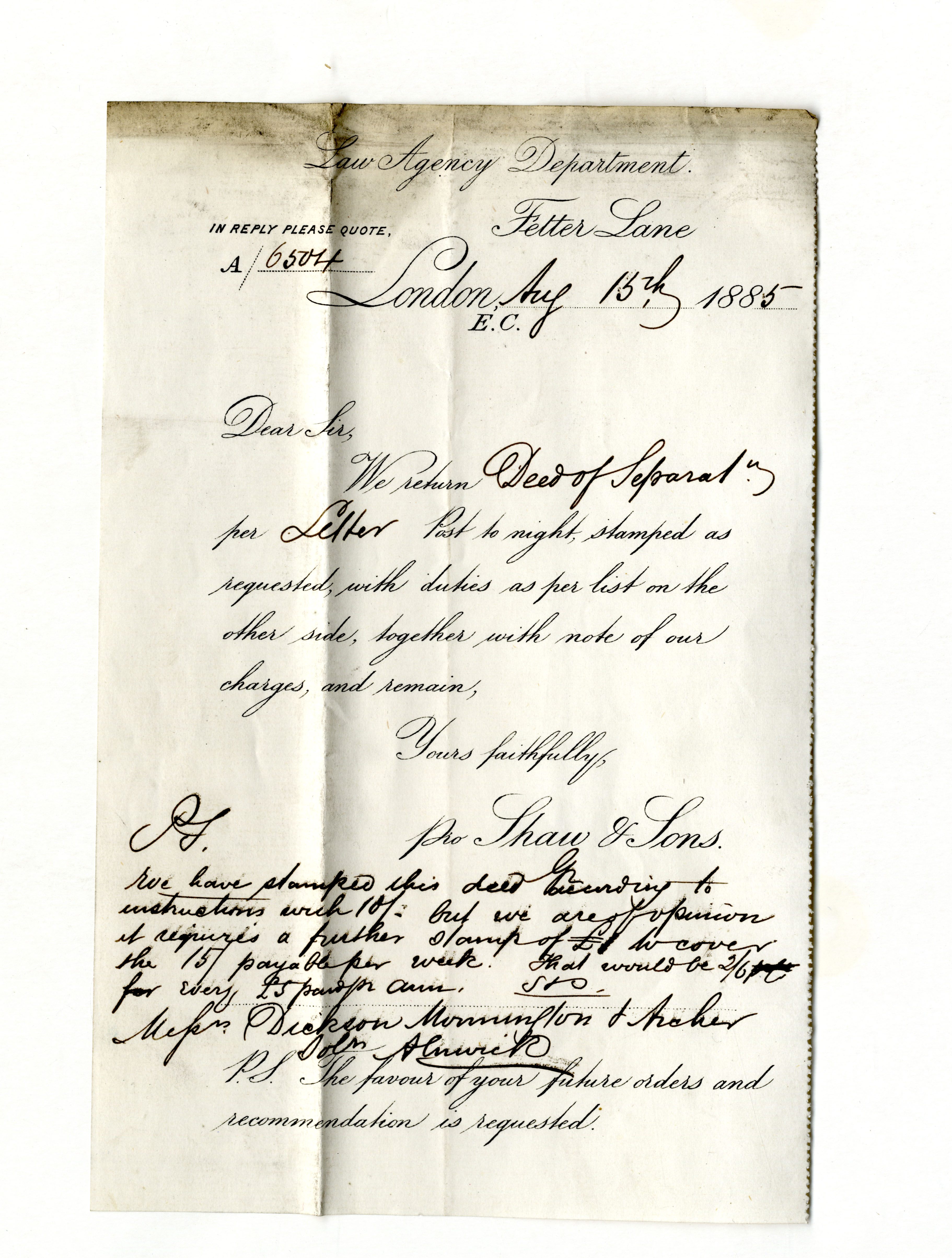

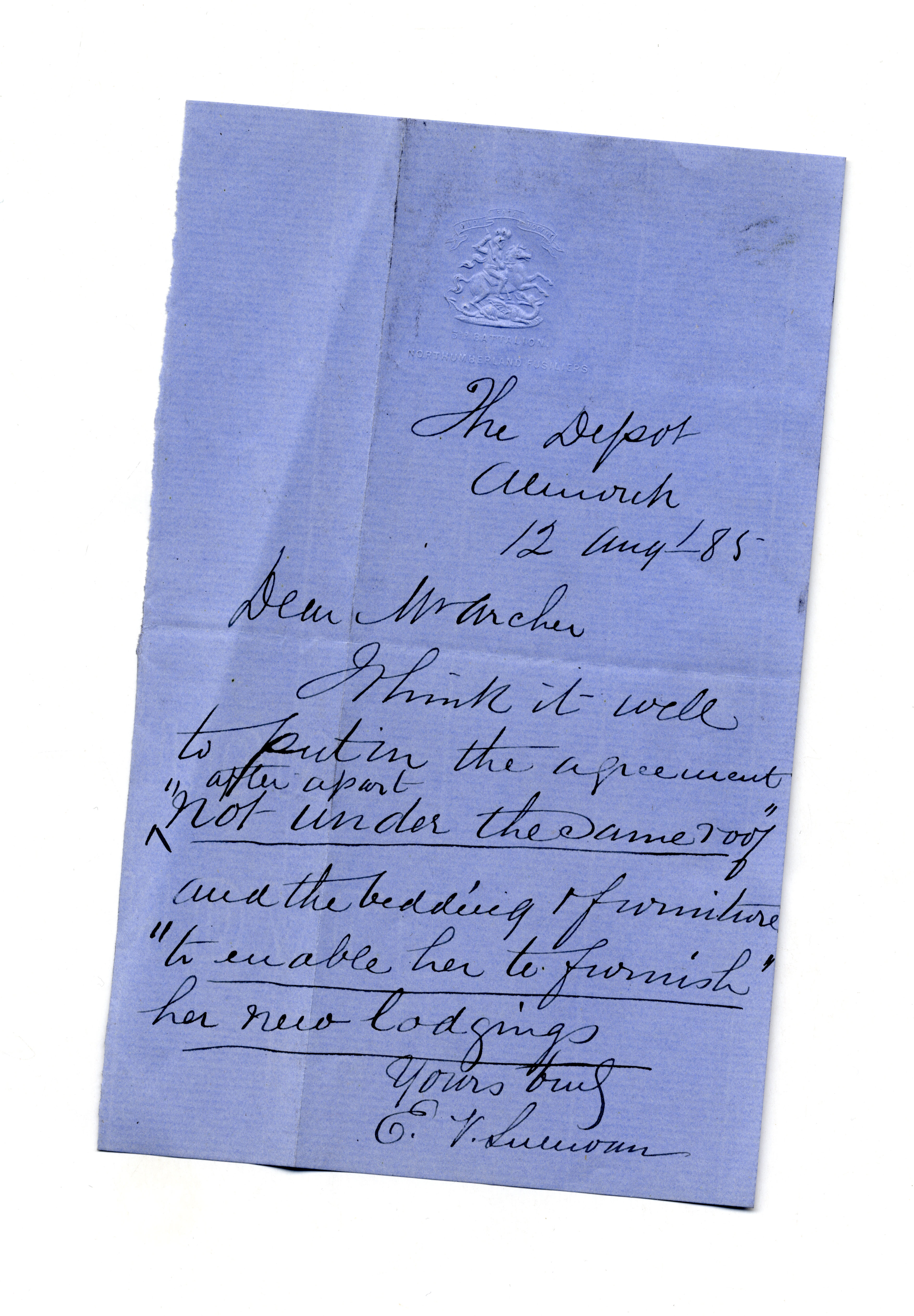

Bertram survived the accident seemingly unscathed but, following the birth of his only child, it seemed to “intimates” that “Mr. Lisle’s brain was weakening, and for a prolonged period he was under the night and day supervision of three male nurses in his own home.” Frightened at his son’s rapid decline Bertram’s father allowed for him to be operated on at Morningside Royal Infirmary. He survived barely a fortnight before dying in his Edinburgh hospital bed during November 1893. Upon his death the barrister-at-law left an estate equaling £1745.8s.6d to his widow Jane Lucinda and Thomas Alder Thorp, a friend from his Alnwick legal circle. Thomas Alder Thorp was a main partner in the county’s well-known Dickson, Archer and Thorp legal firm. Found amongst the firm’s papers, now held by the Northumberland Archives, was a scrapbook of newspaper clippings. This fascinating item traces the history of Alnwick folk through their criminal misdemeanors, and William Lisle was by far its most prolific character.

Following his father’s untimely demise William appears to have floated between relatives. In retrospect, relatives stated that they knew his father’s early death meant Beresford would likely become “a troublesome lad.” William did not disappoint – running away from his boarding school twice. In 1908 he gave his address as Bailiffgate, Alnwick – the previous home of a William Beresford Lisle (potentially his grandfather) who had died in 1903 leaving an estate of £1869.19s.11d. There is substantial evidence to support the notion that William the younger received consecutive inheritances made up of substantial amounts. But this constant flow of money only seemed to fuel his desire to live a ‘fast’ life.

Living on the Wrong Side of the Law

William’s string of good financial fortune brought with it the temptation of fast cars, alcohol and women. His leisurely lifestyle was a one of high jinks and increasingly wild escapades – activities which often found him stood before a judge. Alongside him, pleading his defense, were usually the Dickson, Archer and Thorp firm. These men were clearly close to William’s late father and often persuaded the presiding judges to act with clemency, whilst repeatedly encouraging William to find help from rural rehabilitation centres. Court records repeatedly mentioned a mystery ‘illness’ suffered by William, and often used to explain his wild behaviour. It would appear that this ‘illness’ may have been some form of addiction.

William’s first crime, and arguably his most scandalous, was a motor jaunt taken in the summer of 1907 which led to accusations of drink driving, the abduction of a child and an international gun-fight. Barely two months later Lisle and his motor-car were in trouble yet again when, on August 30th 1907, Lisle arrived in Chester-le-Street from Durham to visit the Lambton Arms. Accompanying him were his chauffeur and a young gentlewoman – possibly his wife. Upon leaving the premises Lisle got into the car and attempted to start it. When the vehicle refused to start he became increasingly agitated, and was further irritated by onlookers querying what was wrong. He eventually got the car to move but, as he did so, it creeped backwards crashing into a shop window. The window belonged to John Byers, a tobacconist and “fancy-goods” dealer, and the accident resulted in £64.11s.3d of damage. At first Lisle accepted liability, but in the days which followed, he changed his story and wholly denied his role. Yet witnesses to the accident attested to seeing him commit the crime, and the judge presiding over the Byers’ compensation case slammed Lisle’s actions labelling him as an inexperienced driver who should not have been behind the wheel.

The year of 1907 did not close quietly for Lisle, as he was once again hauled before the courts to stand alongside George Taylor and Albert Ferguson when accused of poaching game and trespassing. The men were said to have used a motor-car to stalk the countryside and woodland surrounding Felton and gun down game. These activities resulted in a judge binding Lisle over with a hefty sum; in return for good behaviour. When passing his sentence the judge commented that Lisle had many more upcoming court dates for additional crimes of a more ‘serious nature’.

It was during the October of 1908 when Lisle really began to spiral and developed a certain notoriety for criminal high jinks. At the beginning of the month he was placed before Bow Street Police Courts for attempting to steal an automatic money box attached to one of the lavatories in Leicester Square’s Tube Railway Station. A witness claimed to have seen him attempting to release the box from its fixings using a chisel. The court heard that Lisle, who gave no fixed address and was listed as being twenty two years old, had been reduced to stealing the money box having inherited a vast fortune of £5,000 with a £10,000 annuity which he had completely blown within eight months. He was described as looking “ill and dejected as he stood in the dock, … leaned heavily on the rail, with his head bent” and his solicitor Mr Dixon (possibly a mispelling of Dickson) had advised him to admit his guilt. Mr Dixon argued that the crime had been the result of heavy drinking and that Lisle did not need or want the money in the box. The solicitor claimed that, should the young man need money, he could ask his friends in the North. He then argued that his client needed medical attention not jail, and the judge praised Dixon (Dickson) for his kind and considerate treatment of a client. The judge then agreed with the defense, and bound Lisle over with a value of £200.

Following this particular court case Lisle sought treatment and entered himself into a rehabilitation hospital. But, after only two days, he discharged himself and headed straight to Romano’s restaurant in London where he enjoyed a lavish meal. However, upon receiving the bill, he “suddenly realised” that he lacked the sufficient funds to pay and was hauled once again before the Bow Street Police Court for obtaining credit by fraud. The judge once again acted leniently and this time he was forced to enter a rehabilitation retreat for twelve months.

During his time in treatment another case was heard against him, this time in Newcastle’s magistrates court. Here he was accused of discharging a revolver in the “danger of passengers” on Shields Road West, Newcastle during the previous April. Lisle was represented in this case by a Mr Lambert, yet he received no formal punishment on accord to being forcibly housed in a protected rehabilitation center. After discharging the revolver Lisle appears to have gone on the run. The police, working on false information, believed him to be hiding in Eleanor Maud Reidford’s lodging house on Westgate Road. The house was popular with theatrical workers and the police decided to storm and search it. Involvement with the police in such a violent crime caused the business to loose clients, and the whole affair tarnished Reidford’s reputation. Reidford would later bring a case of defamation against the Newcastle Corporation for her treatment.

In 1909 Lisle was again held before the court for the offence of theft; reportedly committed against his own family. This crime took place at the home of Lisle’s father-in-law in Lish Avenue, Whitley Bay. During the court case Lisle’s in-laws testified to his odd behaviour, and claimed that Lisle had stolen money and goods before wrecking the dwelling to make it unlivable.

The scrapbook obsessively records other court appearances, extending into the 1920s, which clearly exasperated the Dickson, Archer and Thorp lawyers. One of whom, Thomas Alder Thorp, told an assembled court in 1907 that “It appears nobody can prevent him from doing these things if he wishes to do so.”

A Timeline of Crime

1907, June: Abducts Louisa Rose Whittle, 15 years old, and Theresa Roper, 17 years old.

1907, August: Car crash at Chester-Le-Street, causing considerable damage to a shop window.

1907, December and 1908, January: Repeated offenses of trespassing and poaching game.

1908, October: Attempts to steal an automatic money box, attached to one of lavatories at Leicester Square Tube Railway Station.

1908, October (only a few days after prior offence): Stands accused of obtaining credit by fraud at Romano’s Restaurant, London.

1908, October (following prior two offences): He is taken to a ‘home’ at Huntingdon (probably some form of rehabilitation retreat) to stay for twelve months.

1908, November: A case against him is heard before the magistrates but he does not appear. He is accused of discharging a revolver during the previous April in the “danger of passengers” on Shields Road West, Newcastle.

1909: At the Northumberland Assizes Eleanor Maud Reidford accuses the Newcastle Corporation of slander and defamation of character having lost business from the police (working on false information) circling and entering her lodging house on Westgate Road in their search for Beresford Lisle.

1909, October: Lisle is accused of attempted theft from his father-in-law’s property on Lish Avenue, Whitley bay.

The information held in this blog has been extracted from original documents held in the Dickson, Archer and Thorp collection as well as contemporary newspapers. A special credit is given to British History Online for access to Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster Part 1 ed. by FHW Sheppard (London, 1960).