We have covered John Atkin’s life in our previous blog, but now will look at the younger generation of the Atkin family and their relationship with Stannington.

Robert Atkin

Robert was born at Stargate, near Ryton 1882, where his father John was working as a colliery Blacksmith. He followed his family in their various moves, though he and his sister Minnie lived with their grandparents during the 1891 census, and settled with the family at Whitehouse farm. He is described as a Gardener on the 1911 census. He served in the First World War, and there are two medals roll index cards that may refer to him, both showing a private in the Northumberland Fusiliers that received service medals. He met nurse Hilda Currie at the sanatorium, perhaps through the gatherings and dances that were held for staff.

Robert is one of the staff from Stannington Sanatorium and the Philipson Farm Colony who served in the First World War that are being researched in a new project. As part of the Stannington Parish Centenary Festival of Remembrance (8-11th November 2018), Richard Tolson is producing a series of books looking at Stannington parish 100 years ago, and recording the story of the men who left the parish to fight in the First World War.

The festival is intended to involve the whole community and will include a flower festival, book signing, School trips, WW1 Re-enactments, village dance, brass band concert, a talk about the WW1 history of the village, displays of the research, and a special Remembrance Service. For more details, or to help out with any relevant photos or information contact Stannington History Group via stanningtonhistorygroup@gmail.com

Hilda Currie

Hilda Jane Currie was born in Percy Main or Willington-on-Tyne in 1892. Her father was Captain John Currie, a master mariner, and her mother was Georgina Margaret Robinson, recorded on the census as Meggie. She grew up with sisters Meggie, Ella, and Eva, and her brothers John (known as Jack) and James Herbert. The brothers served at sea in WWI, and they seem to have been a very close family, sending letters from the various parts of the world they travelled to. Jack became an engineer in the Navy, and was killed aboard the SS Whitgift 20th April 1916 in a submarine attack, aged 32. James was a Mercantile Marine, 3rd engineer on the SS Northumbria. On the 9th Jan 1919 he was killed by a mine explosion at Newbiggin-by-the-sea, aged 29. Jack is commemorated on Tower Hill memorial, and James is buried at Wallsend (Church Bank) Cemetery.

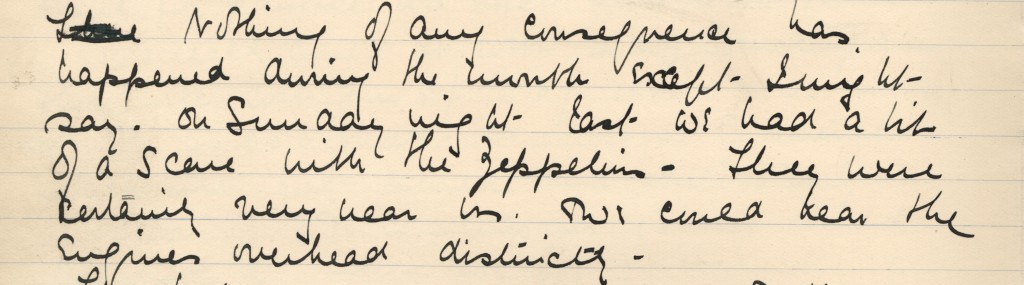

In 1911 Hilda and her sister Ella are not recorded with their mother and other sisters, but were visiting Anne Isabella Richardson, perhaps an aunt, in Willington. She must have gone into nursing sometime after this, and from the album we know she would have been at Stannington around 1915. She was there when her brother Jack wrote to her from the SS Whitgift on the 24th June that year, saying he was glad she was enjoying her new job. A photograph in the Album titled ‘London Hospital Nurse’s training home, Tredegar House, Bow’ suggests she may have learned her skills there. It is clear from her album that Hilda forged some very strong bonds with her young charges, and we see them in her photographs around the grounds, in costumes, and even photo postcards from after their discharge.

The Atkin family moved to The Birches in Tranwell Woods, and John built the family a home there in 1910, named White House after the farm. Robert and Hilda married in late 1922, and moved into the Birches, later moving into the White House after John and Margaret died. The family lived there for many years, with successive generations building and living around the two houses.

Hilda’s album

Hilda collected a fascinating album of photographs from her time at Stannington and her later, which has very kindly been deposited with us by her granddaughter. In it we see many snatched moments of quiet for the staff, and fun for the staff and patients. Below we have included some of our favourites such as the 1922 PCHA trip to Cresswell beach, Matron Campbell off duty, and a nurse riding sidecar on a motorbike. We think it shows a very personal view of Stannington around the time of the First World War, and if you would like to see more of them they are now available to search using the reference NRO 10361* through our online catalogue.

Northumberland Archives would like to say a huge thank you to Hilda and Robert’s granddaughter for depositing Hilda’s album with us, giving us permission to use the photographs in the blog, and supplying further information and photographs which have helped us to explore the Atkin family’s connection with Stannington.