As the Northumberland Summer Assizes assembled on the 18th July 1887 Elizabeth “Longstaff” stood trial charged with the larceny of two bed sheets worth three shillings. The bed sheets had been relieved from an Amble lodging house belonging to Obadiah Self; a coal miner with three daughters and a son. Obadiah testified to the assembled court that, on the afternoon of the 9th July 1887, he had made-up the lodging house’s ten beds. At 10:30pm, when he went to check on the beds, he found two sheets missing.

An Elizabeth “Longstaff” had been lodging at the house and her disappearance on the evening of the crime made her the most likely perpetrator. Having absconded from the scene she tried to rid herself of the evidence. She met Margaret Gilmore from Broomhill and told her that she “was hard up and … would sell the sheets for the price of a stone of flour and a bit of yeast.” Margaret then unknowingly bought the stolen sheets for one shilling and a loaf of bread. Obadiah had immediately reported the incident to the local Police Sergeant and, as Elizabeth returned from her dealings on the Radcliffe to Amble railway, Lewis Scaife, the local Police Sergeant, was able to identify and apprehend the suspect. Elizabeth immediately admitted her guilt to the Sergeant.

Elizabeth was further incriminated during the trial by the prosecution’s key witness Frank Mack; an Amble-based hawker of no fixed aboded. He had also lodged in the house that fateful night and told the court how he had innocently helped Elizabeth gain entry to the bedroom as she could not open the heavy door. She was eventually found guilty by the presiding Bench and the case made headline news in the Morpeth Herald as an example of “bad character.”

Elizabeth’s 1887 court appearance appears to be the first, and only, time the Dickson, Archer and Thorp firm were involved in the prosecution of a Mrs “Longstaff.” However, Mr Archer believed her crimes extended far beyond the parish of Warkworth. To prove his hunch Mr Archer sent various letters to contacts across the Durham county. A picture of Elizabeth soon emerged of a colourful character whom had carved herself a career in crime. Her previous convictions included indecent exposure, drunk and disorderly behaviour, the theft of money and food, passing of counterfeit corn, use of counterfeit coins and larceny of clothing. This extensive criminal record can be traced from 1887 to 1900 using newspaper articles, criminal registers and original documents produced for the aforementioned court case of 1887.

Elizabeth Johnson

Elizabeth was born in 1857 as Elizabeth Johnson. She hailed from Sunderland in County Durham, and married Miles Longmires in 1876. Their marriage was a turbulent one; which Elizabeth yearned to escape.

On the 10th January 1879 reports were published in the Durham County Advertiser regarding a domestic assault which had occurred between the couple in the October of 1878. Miles Longmires, described as being a potato hawker, had assaulted his wife Elizabeth by delivering a strong blow to the back of her head. Elizabeth had pressed for charges immediately following the incident, but she subsequently dropped them. Whilst being questioned as to why she had dropped the accusations against her husband she changed her version of events to divert the blame. She claimed she was struck by someone in the dark passageway of their lodgings, and had blamed her husband. She then claimed she had been mistaken and, having been informed by her more knowledgeable “neighbours,” the assailant had actually been another resident at the Coxon Lodging house called John Jones. We will never know why Elizabeth changed her story but, having escaped to her mother’s home for a short time, she returned to her husband and in 1879 gave birth to the couple’s only child John William.

But the birth of their child did not lesson Miles’ temper, and his domestic abuse of Elizabeth continued. By the November of 1879 this behaviour had pushed Elizabeth to take drastic measures, and led to her first brush with the law.

A Poisoned Beer

John Lewis was a business acquaintance of Miles Longmires and known throughout the county as “Partridge Jack.” On the 5th November 1879 the elderly man had went to the Longmires’ household to conduct business, whilst there John gave Elizabeth one shilling to procure him something to eat. Upon her return all Elizabeth had purchased was beer, to which she added a brown powder claimed to be allspice. The concoction made John ill, and Elizabeth told the old man to lie down. John obliged and, as he was emptying his pockets, Elizabeth grabbed one of his satchels of money and “bolted out of the house, locking him in.”

Whilst John attempted to escape through a window, Elizabeth had retreated with her infant son to a neighbour’s home and told them that she had “cleaned Miley out.” This comment was a clear reference to having gained revenge over her abusive husband by ruining his business deal and escaping. She took the money, burned the satchel and fled with her son. However, she was soon caught a few days later at Spennymoor by PC Houlds. The policeman testified in court that, when found, she admitted to having spent the money on new clothes for herself and her child. John told the police that he had been carrying at least £10 but, when apprehended, Elizabeth claimed it had only been £3.

On the advice of her solicitor Elizabeth took responsibility for her actions and pleaded guilty when she then appeared in the dock with “an infant in her arms.” The infancy of her child and her honesty, which was to become a pattern in her court appearances, did not gain her mercy from the Bench. Instead, “the Bench considered this a very bad case, and the prisoner was therefore ordered to undergo the heaviest penalty in the power of the magistrates, six months hard labour.”

A Time Line of Crime

Elizabeth served her sentence but in the October of 1880, less than five months after her release, she was imprisoned again for “obtaining goods by means of false pretences after a previous conviction.” Perhaps Elizabeth actively sought to be imprisoned in an attempt to escape her turbulent home-life? However, as her criminal spree continued long after her husband died a premature death in 1882, it was more likely influenced by her economical situation.

In the 1881 census Elizabeth was residing in Durham Prison, here she is listed as being a “fish hawker” beyond the prison walls. Those who worked as hawkers were often loud and charismatic people; able to barter and manipulate a situation to gain a sale. Victorian hawkers often walked a thin line between legal trade and loopholes. Some operated with licences, but many sold a mix of legal and black-market items in an ad-hoc way. It was an unstable lifestyle, which didn’t always guarantee money, and often became a gateway to crime. Thus her tendency to steal items which she could easily pass on for a profit, such as clothing and material, may have been rooted in her “occupation.”

Following her 1880/81 stint in Durham gaol Elizabeth moved to Northumberland and developed her criminal repertoire. It was around this time that Elizabeth also began to use a collection of aliases whilst committing her crimes. This made it harder for her prosecutors to prove previous criminality – as Mr Archer experienced first-hand. These aliases included her married name of Longmires, her maiden name Johnson and two invented names of Longstaff/staffe and Clayton.

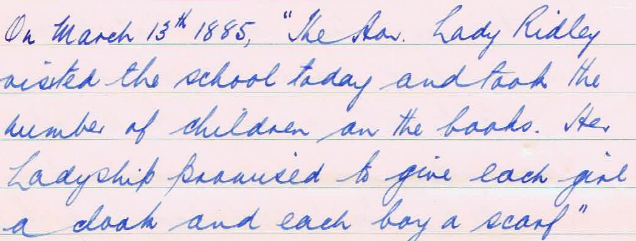

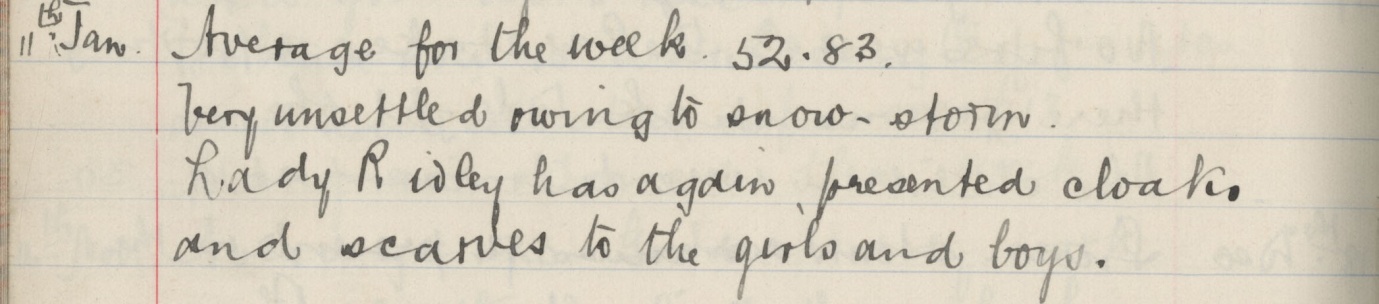

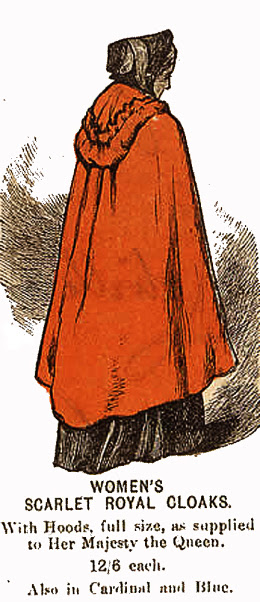

In January 1886 she was convicted at Northumberland’s Epiphany Sessions, held at the Moot Hall in Newcastle, for the use of counterfeit coins. She received a prison sentence lasting 12 calendar months, along with a three year police supervision order. It was following her release from this particular crime that Elizabeth stole Obadiah Self’s bed-sheets, for which she received two months hard labour.

The following year Elizabeth was free once more and returned to Durham, where she proceeded to commit two separate crimes of “simple larceny.” The first occurred in June, and she received a second police supervision order. However, by the October she had stolen another bedsheet (this time from an Edward Toole.) For this crime, and because she had broken the rules of her previous supervision order, she was sentenced to six months hard labour.

In September 1889 she returned to prison again for “14 days” having failed to report herself to her Police Supervisors in Auckland whilst on a “ticket of leave.” Then, in the December of 1889 at the age of 33, she returned to prison for five years having stolen:

“a piece of ham, a shoulder of mutton, a quantity of flour, six yards of black velvet, one hat, one pair of cotton sheets, one black skirt and two pairs of stockings, value £1 4s, the property of Margaret Crawford at Jarrow.”

Her lengthy jail time gained her some sympathy when she offended once again in 1894 for stealing a quantity of clothes belonging to William Liddell at Cowpen. During this trial it was noted that;

“The Bench were sorry to find she had spent most part of her life in prison, the last sentence she had undergone being five years’ penal servitude. She was even now out on ticket-of-leave. She would have three more years’ penal servitude after she had completed the unexpired one on which she was now out.”

Escape to Yorkshire

By the close of the century Elizabeth had spent extensive periods in a series of northern prisons. In 1899 she was charged once again, this time in Blyth’s Police Court, for failing to report a change of address whilst on another ticket-of-leave. It is assumed her new address was somewhere in Yorkshire as, later that year, she spent fourteen days in HMP Wakefield for the crime of “begging.” The admittance register for Wakefield HMP describes Elizabeth’s physical features as standing at just over four foot tall with grey hair. The register also notes that she was illiterate. Elizabeth was now 42 years old with twelve previous convictions.

Elizabeth’s story is difficult to trace from this point forward; she may have died or changed her name again. Her son, John William, seems to have grown up away from Elizabeth. Tracing him is also difficult; but there was a John William Longmires born in the county of Durham and working as a barber in the Alnwick workhouse in 1901.

Elizabeth’s adult life had been spent mostly incarcerated, and her petty crimes had kept the county’s magistrates busy. A mix of Elizabeth’s marital, economic and social situation forced her hand to crime. Her first serious crime against “Partridge Jack” seems to have been an attempt to escape a violent life. It is easy to fall for the Victorian rhetoric and see Elizabeth as an enterprising criminal but it was more likely that she was a victim of her time, sadly restricted by her social context.