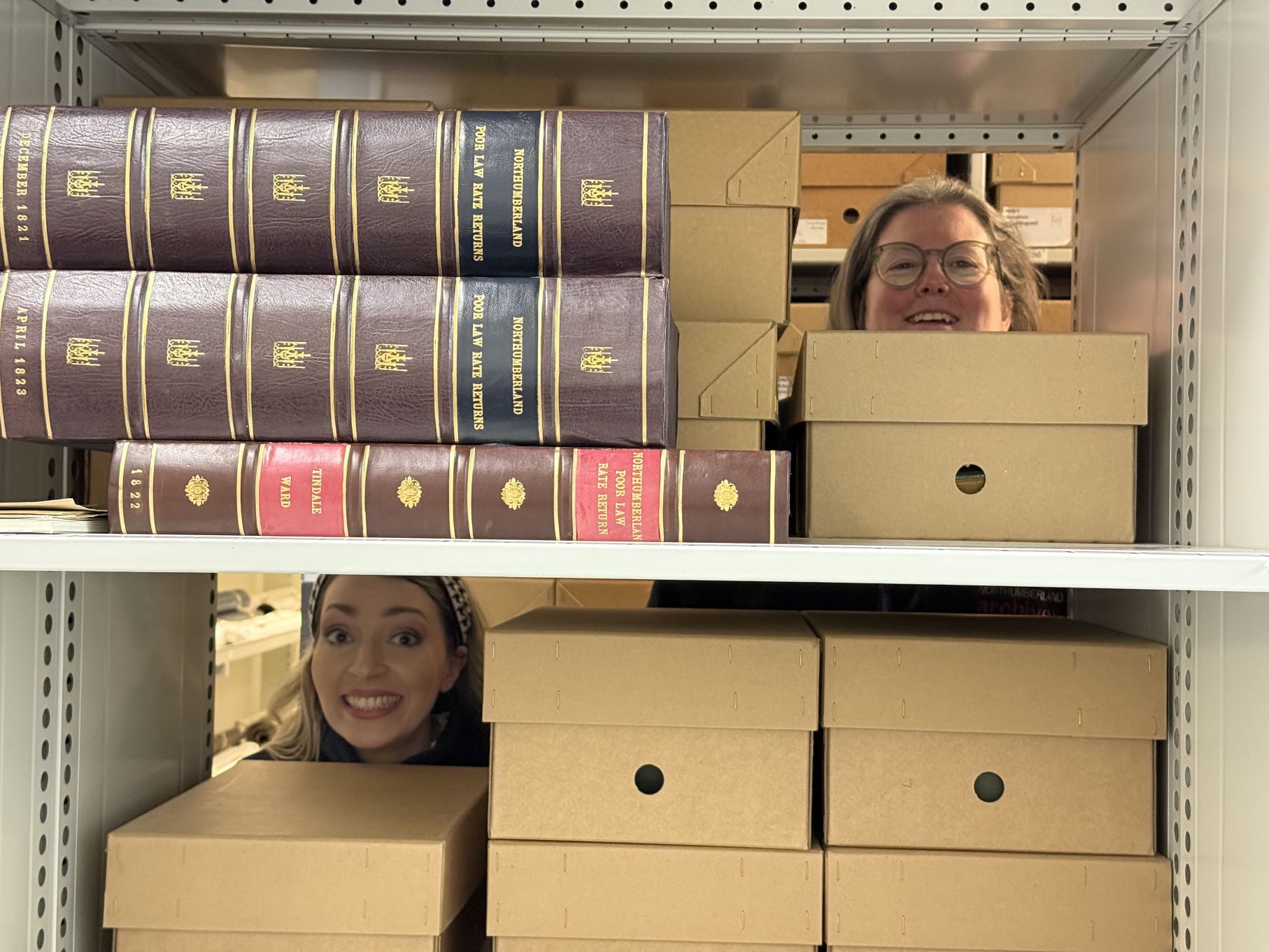

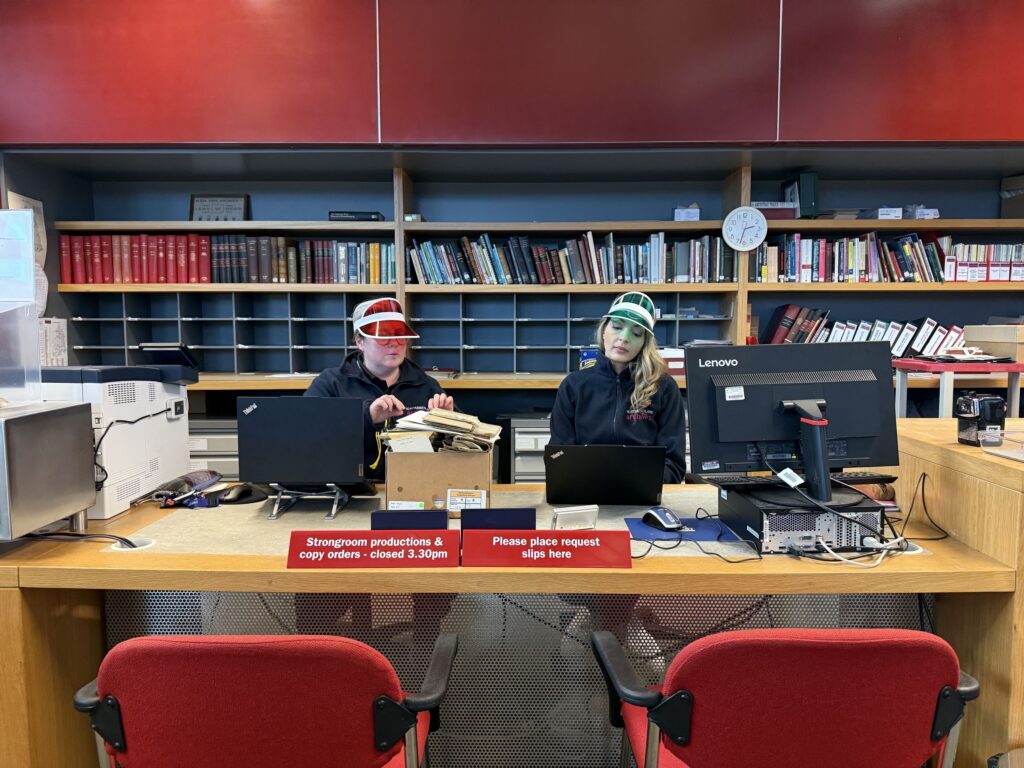

Back in October, Northumberland Archives was lucky enough to attract two fantastic new Archive Assistants – Jemma and Helen. (Hang on – has somebody let Jemma and Helen write the intro?) We asked them to interview each other to find out how they’ve found their time settling into their new roles.

Jemma: What do you enjoy most about being an Archive Assistant?

Helen: I am enjoying how interesting the job is. I have been surprised at the variety of material we hold here – it means that every day I learn something new or come across something that piques my interest.

I’m also enjoying the social side of the archive – there is a lovely atmosphere behind the scenes and everyone has been supportive and keen to pass on their knowledge.

Jemma: What have you found your interests are when working with such a range of archive materials?

Helen: I have found I am particularly drawn to people’s personal testimonies from the past. Reading a letter or a diary, which sometimes mix an account of momentous events in the world with the everyday news of, for instance, what is for dinner or what happened at school or work, feels like a little bridge is created to the past.

Outside of work I write fiction and I am finding it quite inspiring to read people’s stories from long ago and get a little insight into everyday lives.

Jemma: What has been your biggest challenge when working at the archives?

Helen: The biggest challenge has not so much been any singular thing but everything! There is so much to learn that I feel we’ve had to accept not being totally sure what we’re doing for a little while. It has helped to hear more experienced members of staff saying that they are still learning even after working here for years.

Jemma: What was the most surprising/unexpected find for you here?

Helen: When we first arrived we were encouraged to search for anything we fancied looking at just to get used to using the catalogue. I looked up Ovingham, the village I was brought up in, and was interested to discover that we held a newspaper article about a poet who had lived in Ovingham. The article itself was interesting – written in the 1930s it was about Dora Greenwell a poet who was particularly known for writing hymns and who lived in the village for some time in the 1840s – but perhaps more interesting to me was the volume that the newspaper article was stored in. When I went to get the article out I discovered that the clipping was actually in a scrapbook about Ovingham made by a woman, Eliza Charlton, who lived in the village throughout the 20th century. Her entries started with articles and photos about the village school and progressed through various local events to pieces on the WI in the 1980s. I was delighted to come across some names I recognised in the latter part of her scrapbook.

Jemma: What should the public know about Northumberland Archives that you didn’t know about before working here?

Helen: They should know that we have a huge amount of items in our collection so there is bound to be something that interests them. On a pragmatic note, they might be interested to know that they can access Ancestry and Find My Past on the computers here for free and that there’s a lovely café in the museum downstairs!

Helen: How has the reality of working in the archives differed from your expectations? Has anything surprised you?

Jemma: I didn’t expect to be able to physically access so many materials daily and I think this may have been the biggest surprise to me, as well as the enormous amount housed here that is accessible to the public. I knew this would be an interesting job, I just didn’t realise how fascinating it would become.

Helen: What attracted you to work here?

Jemma: My interest in history has always been there from school, but recently my interest in local history has increased massively after starting a family tree. I soon found myself wanting to explore more than just the names in my family history and I wanted to find out about their houses, their towns and their livelihoods. It was this that made me really want to help and be a part of someone else’s journey.

Helen: What is your favourite part of the archive – what have you found most interesting?

Jemma: My favourite part, or place, in Northumberland Archives is the strong rooms where they store all the documents and items. I find the rooms peaceful, as is the search room where the public can access. An aspect of the Archives that I’ve found the most interesting is the information on coal mining – be it maps, photographs, transcripts or diaries of those who have worked in a Northumberland colliery. Having family who have worked in collieries in this area and specifically in Woodhorn colliery itself, makes every bit of information surrounding this topic interesting to me and it feels a little bit personal too.

Helen: Is there anything you’ve struggled with?

Jemma: Learning how to approach different family histories when customers request help was more difficult than I anticipated. More times than not it isn’t straight forward and sometimes people are starting from the beginning, with no previous family knowledge and so it becomes a bit of a hunt. However, when you help someone from this starting point it feels like you’ve made a real achievement.

Helen: What are you looking forward to mastering?

Jemma: The organisation and work that goes into the full process of obtaining documents to them becoming accessible to the public is extensive. The staff here are excellent and because of the hours of work and enjoyment that goes into each collection, everyone has their own little interest or expertise in an area. I’m really looking forward to carrying out each bit of this process and then from there developing my own area of knowledge…which would be around Northumberland’s coal mining history (my Grandad would be proud).