Examination and Diagnosis

On the 30th day of November, in the year 1860, two surgeons came to a home in Narrowgate, Alnwick to examine a Mr William Marshall for proof of “insanity.” The medical examination had been arranged by William’s family and facilitated by Hugh Lisle Esq, a local Justice of the Peace. William’s story, pulled from the Dickson, Archer and Thorp collection, allows us a unique insight into the lives of those diagnosed “insane,” and the families they often left behind, in nineteenth century Northumberland.

The surgeons examining William were a Henry Caudlish and a Thomas Feuder. In line with the requirements of their positions all three men completed detailed forms evaluating William’s mental well-being. The survival of these medical forms, used to certify William’s illness and record the thoughts of officials, make them rare and insightful pieces.

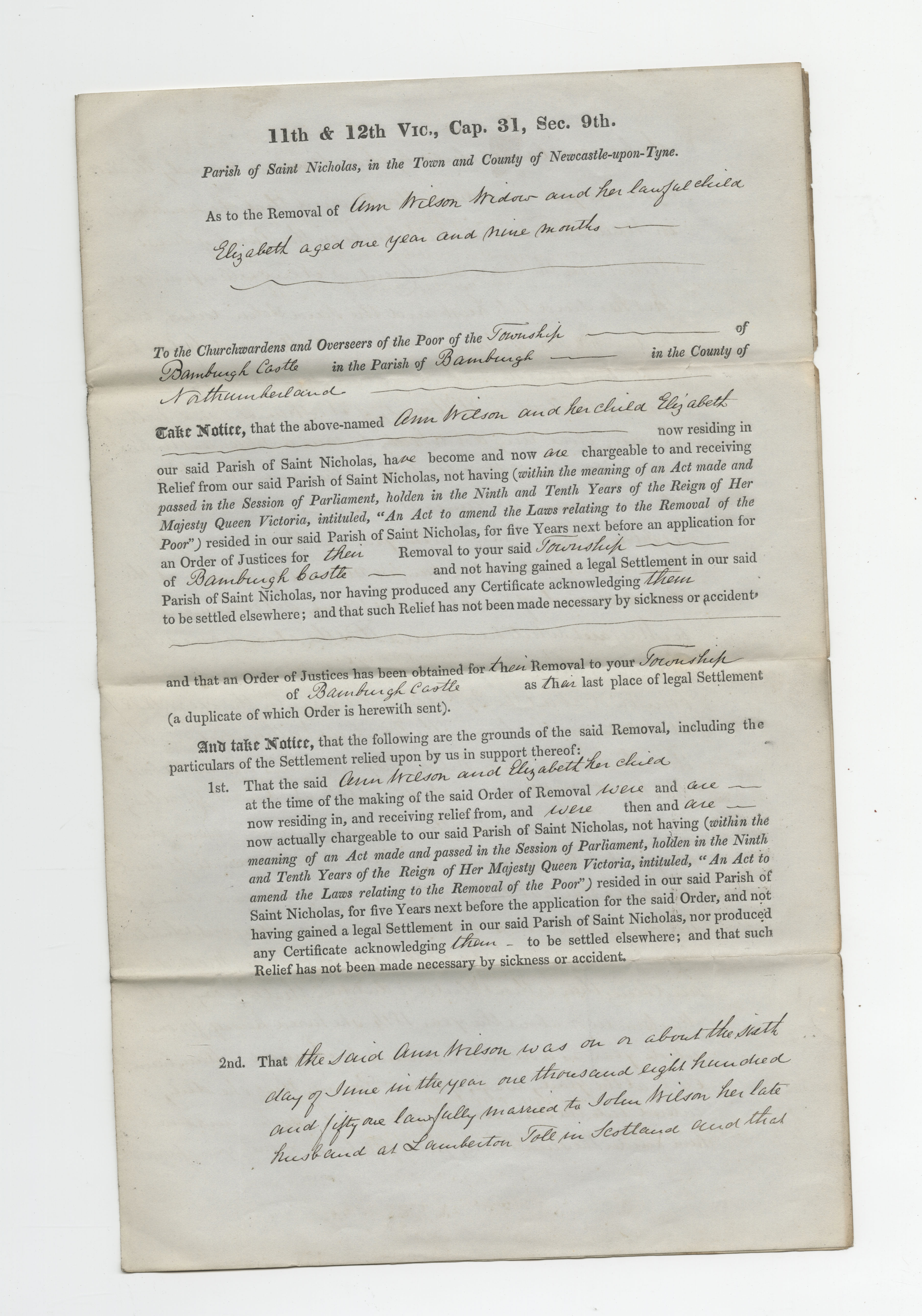

Henceforth are transcribed extracts from these forms, with the originals shown in pictures:

Facts indicating Insanity observed by myself:

Thomas: “He fancies that there are Devils in the bed, or parties going to do him some grievous bodily harm, he fancies that the bed clothes are moving. He is desponding.”

Henry: “He states that I have a desire to poison him, and that I have an interest in doing so and that I were among many conspirators. Fancies that there is poison in his bed – and in his food.”

Other facts (if any) indicating Insanity communicated to me by others:

Henry: “He persists that a great quantity of poison has been given to him, but not yet the fatal dose, and that if he dies a hundred persons will be living for him – communicated to me by his wife.”

Thomas: “He refuses his food and persists that what is presented to him contains poison – communicated to me by his wife.”

For William the visions of devils, paired with his belief that someone was secretly poisoning him, were vivid and terrifying. Yet the surgeons found a conspiracy unlikely, and they concluded William was indeed suffering from “insanity.” Upon the diagnosis Hugh Lisle arranged for William to be taken from his home to reside in the Northumberland County Pauper Lunatic Asylum, Morpeth. But why was William suffering with such terrifying visions? And what life awaited him in the county asylum?

Health and Visions

William was not the only patient sent to reside in the Morpeth asylum for having paranoid thoughts. The admission book for the asylum’s patients shows that many were diagnosed upon arrival as suffering from “delusional insanity.”

On the arrival of each new patient their symptoms, and the presumed cause, would be carefully recorded. These so-called causes often included hereditary problems and work place accidents. The surgeon’s involved in William’s case noted the cause to his problems stemmed from a mix of pre-existing medical issues, including chronic asthma and general ill health, with “straitened circumstances.”

Family Troubles and “Straitened Circumstances”

William Marshall was 50 years old when he suffered his first bout of psychological illness in the year 1860. He had lived in Alnwick his whole life, along with his wife Mary and their ever-growing brood.

Together the Marshall’s had eight children; Sarah, Isabella, William, John, Mary, Joseph, Thomas and Annie. The Marshall brood had a staggering age range, with the eldest being twenty years older than the youngest. But, sadly, not all the Marshall children reached adulthood, as Thomas died in 1856 aged just five.

William worked as a coach keeper to support his large family, and his sons followed him into coach and horse-keeping professions. In 1861, less than a year after William was removed from the family home due to his supposed “insanity,” his son John was working as a coach smith whilst Joseph was a hostler. By 1871 Joseph had progressed in the world, and is listed in the census as owning what appears to be 4 acres of land (although how he came to this settlement is a mystery.)

Following her husband’s illness Mary needed to find a way to financially support her young family. She subsequently became a cow keeper. Cow keepers often kept dairy animals, such as cows and goats, within their backyards and would use them to make and distribute dairy products amongst their neighbours. William’s daughters also took up professions to support the family, with Isabella becoming a dressmaker and Mary a domestic servant.

Working hard to feed and provide for his ever-growing family, yet still witnessing some of his children die, must have put strain on William’s own health and mental well-being. These demands, teamed with a potentially dubious financial situation, may explain the “straitened circumstances” referred to in his medical report. Thus, it is unsurprising that these pressures began to manifest in his psychological well-being.

The Northumberland County Asylum

Using the asylum’s minute book we know 80 male patients and 77 female patients were in residence when William arrived at the tail-end of November 1860. We also know, from notes made on the asylum’s weekly purchases, that William would have ate a diet of mutton, scotch oatmeal, split peas and livered meat during his first month.

On the 4th March 1861, roughly three months after William had arrived, the asylum received a visit from its Board of Guardians. What they observed was recorded in the institution’s minute book and can be used to give us a deeper insight into William’s experience of the Northumberland County Pauper Lunatic Asylum. During the visit the gentlemen noted that patients had “good bodily health” and were “without exception quiet and orderly.” They recommended enlarging the chapel, and adding blinds to the patient’s dormitories, to encourage godliness and increase patient privacy. Overall the board members were pleased with the asylum, and noted how they had enjoyed a “good laugh” with some of its residents.

To understand more about the Northumberland County Pauper Lunatic Asylum please see one of the archives’ previous blogs on the subject.

The Devil Put To Bed

It is unlikely William ever left the asylum following his 1861 entry. In the 1871 census Mary Marshall listed herself as being a widow, with William’s death having probably occurred less than a year before in 1870. One can only hope William was no longer troubled by devils in his bed.