The second in our series of posts on some of the surgical procedures carried out at Stannington focuses on the use of curettage and a skin graft to treat tuberculous skin infections.

Patient 84/37 was male and aged 13 ½ when he was admitted to Stannington on 16th December 1938 diagnosed with TB of other organs and an old ankylosed ankle joint. He had previously been in the sanatorium from June 1936 to July 1938 suffering from TB of the right ankle which had healed but since his discharge in July 1938 he had developed a tuberculous skin infection on his right ankle overlaying the original tuberculous focus. This sort of infection might be referred to today as scrofuloderma where there is a direct extension of the tuberculous disease from underlying structures, such as the bone, to the skin. A report on his condition on admittance reads as follows:

‘Large sinus R ankle, healed, but skin lower part reddened & thin & scabbed. Healed sinus R knee & 3 healed on thigh and 1 on leg. Mobility good’

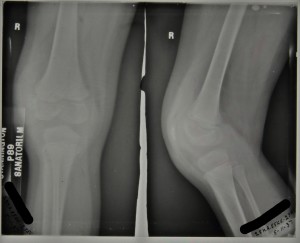

Radiographs taken of his right ankle during his second stay in the sanatorium show the tuberculous ankle to be healed and therefore not causing medical staff any great concern. Figure 1 is a radiograph taken in1939 for which the report reads, ‘no bone lesion in the right foot’, and figure 2 was taken in 1940 with the report stating that there are ‘bony ankyloses of ankle joint’.

Throughout his stay comments in his case file reveal the scar on his ankle to be thin, unsound and broken down. Given that at this time there were no antibiotics available to treat this skin infection a commonly used minor surgical procedure was opted for. On 9th August 1940 curettage was performed on an area on the lateral side of the right ankle with a Thiersch skin graft. Curettage simply refers to the removal of the infected tissue using a surgical tool called a curette. A Thiersch skin graft is a split-thickness graft that can be quite thin and involves the removal of the epidermis and part of the dermis from a donor site elsewhere on the patient’s body, which can then be placed in narrow strips over the wound. By November of 1940 it was noted that the skin graft had taken well, was soundly healed, and that there was good movement of the foot at the 1st metatarsal joint. He was discharged quiescent on 19th November 1940 with the procedure having been a success.

Sources:

B. Kumar and S. Dogra, ‘Cutaneous Tuberculosis’, in Skin Infecitons: Diagnoisis and Treatment, Edited by J. C. Hall and B. J. Hall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009)

L. Teot, P. E. Banwell, & U. E. Ziegler, Surgery in Wounds, (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2004)