Continuing on from our last post on osteomyelitis affecting the lower leg bones, see post dating 06/02/2015, here we are going to review a case of tuberculous osteomyelitis of the short tubular bones in the hands and feet; the metacarpals, metatarsals and phalanges, commonly known as tuberculous dactylitis or ‘spina ventosa’(meaning short or small bone inflated with air). This is a particularly uncommon manifestation of tuberculosis primarily affecting children, and it is rare in anyone over the age of six.

Dactylitis affects the hands more often than the feet and can affect multiple bones at one time. It is caused by the haematogenous spread of tubercular bacteria which settles in the bone marrow of the short bones prior to the epiphyseal centre becoming established. This leads to thickening of the periosteum (outer membrane of the bone) with osteomyelitis, but rarely involves the joint.

Patient 90/27

This patient was a 16 year old male, admitted to Stannington Sanatorium in September 1940 with tuberculosis of the bones and joints, stage II. In this instance tuberculous dactylitis was diagnosed affecting the left foot and right hand, alongside queried primary infection in the lungs and concerns over the right elbow.

The patient’s medical history states that seven months prior to his admission the patient’s left ankle became swollen and started discharging; his 4th left toe became swollen and started discharging and 1 year prior to admission his right hand was hurt and it too became swollen.

Initial observations made by admitting doctors read as follows:

‘Left foot sinus over lateral malleolus,

swelling over 4th toe left foot, discharging sinus at base,

right hand hard swelling of 5th metacarpal’

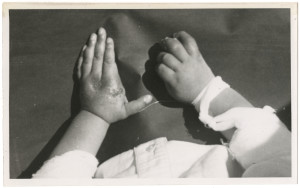

Diagnosis of dactylitis is made based on radiographic findings; however, it is often observable physically due to painless inflammation of the soft tissue surrounding the affected bone. As noted above sinuses may also form, which may discharge, as a result of infection. Although we have no photographic images of patient 90/27, we do have a photograph of another patient (for whom we have no radiographs) also diagnosed with tuberculous dactylitis showing the effects this infection had on the surrounding soft tissue, note the presence of a discharging sinus at the base of the first finger on the left hand, Figure 1.

The first x-ray report for patient 90/27 was in October 1940 and confirmed that the phalange of the fourth toe of the left foot was expanded but without any signs of a cavity; the fibula showed signed of decalcification; fibrosis was detected in the lungs, possibly the primary source of the tubercular infection, and the fifth metacarpal of the right hand was badly affected, Figure 2.

Once established, the tuberculous infection quickly involves the entire marrow space and the tuberculous granulation tissue expands the bone cortex following necrosis of the bone tissue. As a result the bone expands taking on a spindle form and appears much like an inflated balloon. This is well demonstrated in Figure 2, with the balloon like inflammation in the distal metacarpal. It is common to see new bone formation, or periostitis, as a result of the infection. Soft Tissue swelling can also be seen surrounded the affected metacarpal in Figure 2.

Throughout the patient’s notes, specific areas of infection are focussed upon. In April 1941 the x-ray report notes look at the fourth toe of the left foot, Figure 3. Here the proximal phalanx is noticeably expanded and the notes state that the cavity looks as though it has been filled in with granular tissue. By February 1942 the disease has taken over the whole of the phalanx and a cavity is noted in the distal end of the bone.

There is nothing within the patient notes about any specific treatment this patient was receiving for his condition. Given the nature of the infection and the continuous references to ulcers and sinuses that were discharging it is likely these would have been drained regularly as part of the general sanatorium treatment, alongside rest and fresh air. There is one side note within the notes that questions excision of toe, however this is not pursued anywhere else.

With tuberculous dactylitis, it is possible to achieve almost complete recovery. New bone formation around the affected bone is noted, but soft tissue swelling abates and deformity is rare, Figure 4. In April 1942 this patient’s notes read:

‘Nil active in lungs.

Foot: cavity in bone of 4th phalanx filled up. Quiescent.

Hand: metacarpal improving’

This patient was later discharged in May 1942 as ‘improved.’

Further radiographic images can be seen on the Stannington Sanatorium ‘Radiographs from Stannington’ Flickr stream https://www.flickr.com/photos/99322319@N07/sets/72157648833066476/

Sources

Bhaskar, Khongla, T and Bareh, J (2013). Tuberculous dactylitis (spina ventosa) with concomitant ipsilateral axillary scrofuloderma in an immunocompetent child: A rare presentation of skeletal tuberculosis. Advanced Biomedical Research 2:29

Mishra Gyanshankar, P, Dhamgaye, T.M. and Fuladi Amol, B (2009). Spina VentosaDischarging Tubercle Bacilli – A Case Report. Indian Journal of Tuberculosis 56: 100-103

Roberts, C and Buikstra, J (2003). The Bioarchaeology of Tuberculosis: A Global View on Reemerging Disease. Univesity Press of Florida.