When the PCHA created Stannington Sanatorium in a bid to combat Tuberculosis (TB) they were not alone in the fight against the disease. In 1906, the year before Stannington Sanatorium opened, the National Association for the Prevention of Consumption highlighted to local authorities that deaths from the disease of 60,000 people each year in England and Wales were preventable if they acted.

Northumberland County Council acted by urging district councils to notify them of cases of disease, punish spitting, appoint health visitors for sufferers and their families, and place strict controls on dairies. However they put great emphasis on the district councils to improve the major problem of sub-standard housing. As one County Medical Officer put it ‘Tuberculosis is a housing disease’.

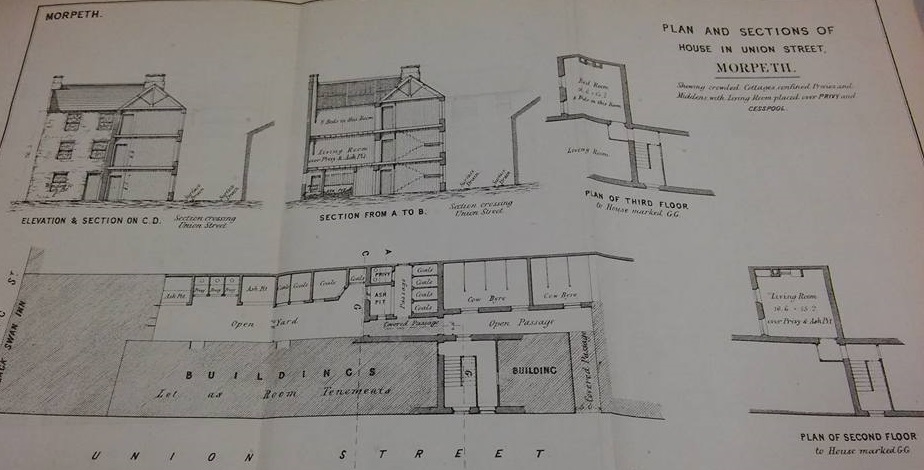

A pamphlet from 1849 titled Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Inquiry into the sewerage, drainage [etc…] of the borough of Morpeth and the village of Bedlington by Robert Rawlinson (NRO 2164) shows just how bad this could be. Rawlinson described the collier’s cottages of the area, where a flagstoned 14ft square room served as living room and bedroom for a large family, with a small bedroom in the roof space ‘open to the slates’. Other houses like the above in Morpeth, had a 16ft by 15ft bedroom in which 8 people slept. Worse however were the overcrowded lodging houses. He quotes the Town Clerk’s account of them, where beds were occupied by ‘as many as can possibly lie upon them’. When these were full others would sleep on the floor in rows. The Town Clerk added ‘nothing but an actual visit can convey anything like a just impression of the state of the atmosphere… what then must it be like for those who sleep there for hours?’ This description shows an atmosphere in which TB could easily spread, where the occupants of the lodging houses (often labourers moving between work) could then spread it at the next lodging house they came to.

However if you think this only happened in the mid-nineteenth century, think again. Dr Allison, who worked for many years at Stannington, described the inside of a house he had visited in 1905:

In the five years leading up to 1914 it was calculated 92 people for every 100,000 in the county died of consumption. This was more than Scarlet fever, Diphtheria, Enteric fever, Measles, and Whooping cough combined, as these diseases together killed 70 people in every 100,000 (NRO 3897/4, 1914, p.26). Notification of cases became compulsory, and the County Medical Officer was under a lot of pressure when asked to assist TB sufferers, and so a full time post was created for a Tuberculosis officer from January 1914. Tuberculosis dispensaries with the TB officer and nurse were established in densely populated areas (NRO 3897/4, 1914, p.25). During the 1920s one in every ten deaths in Northumberland was caused by TB, and the County Council used around 75% of their health expenditure to tackle the disease.

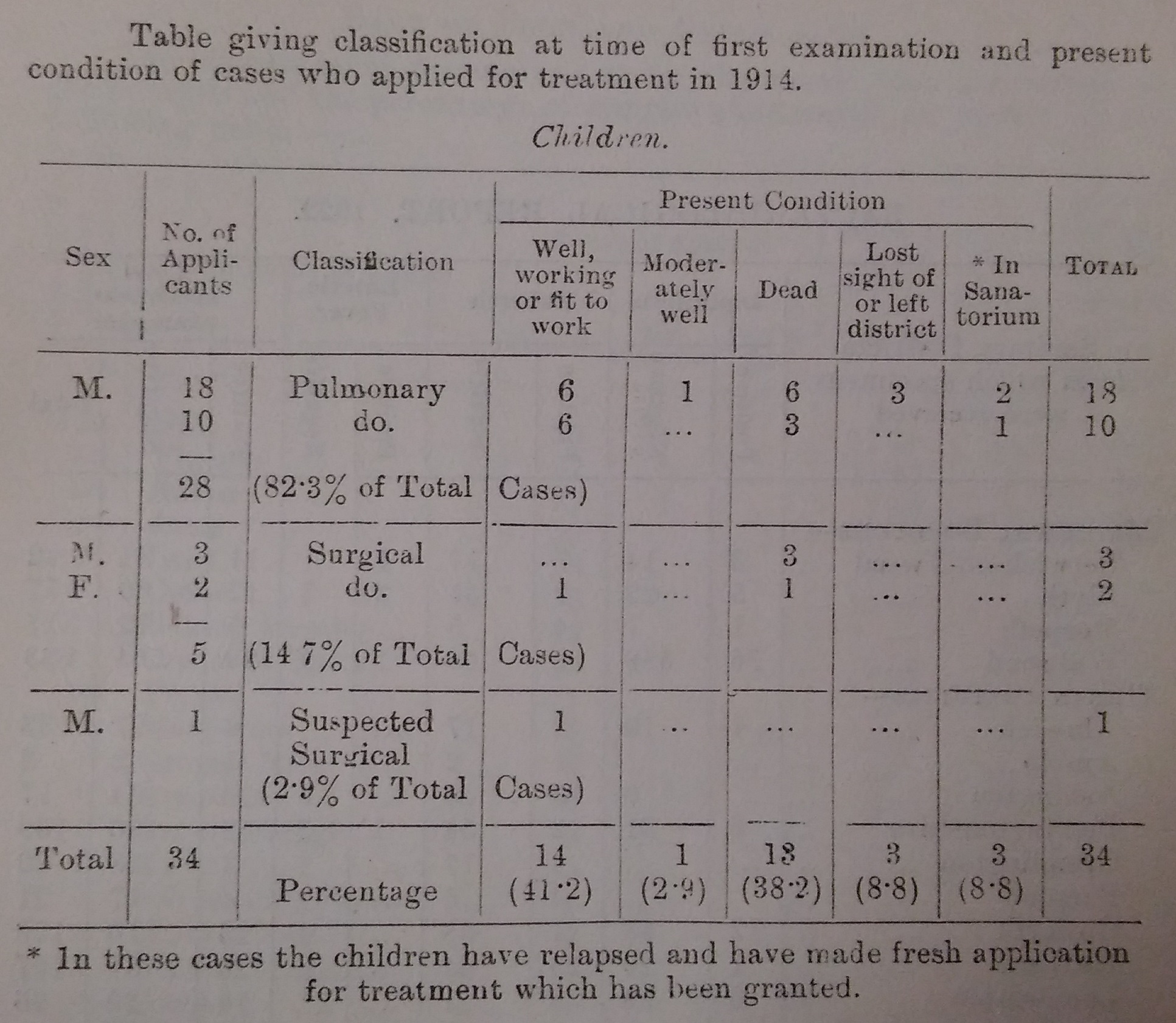

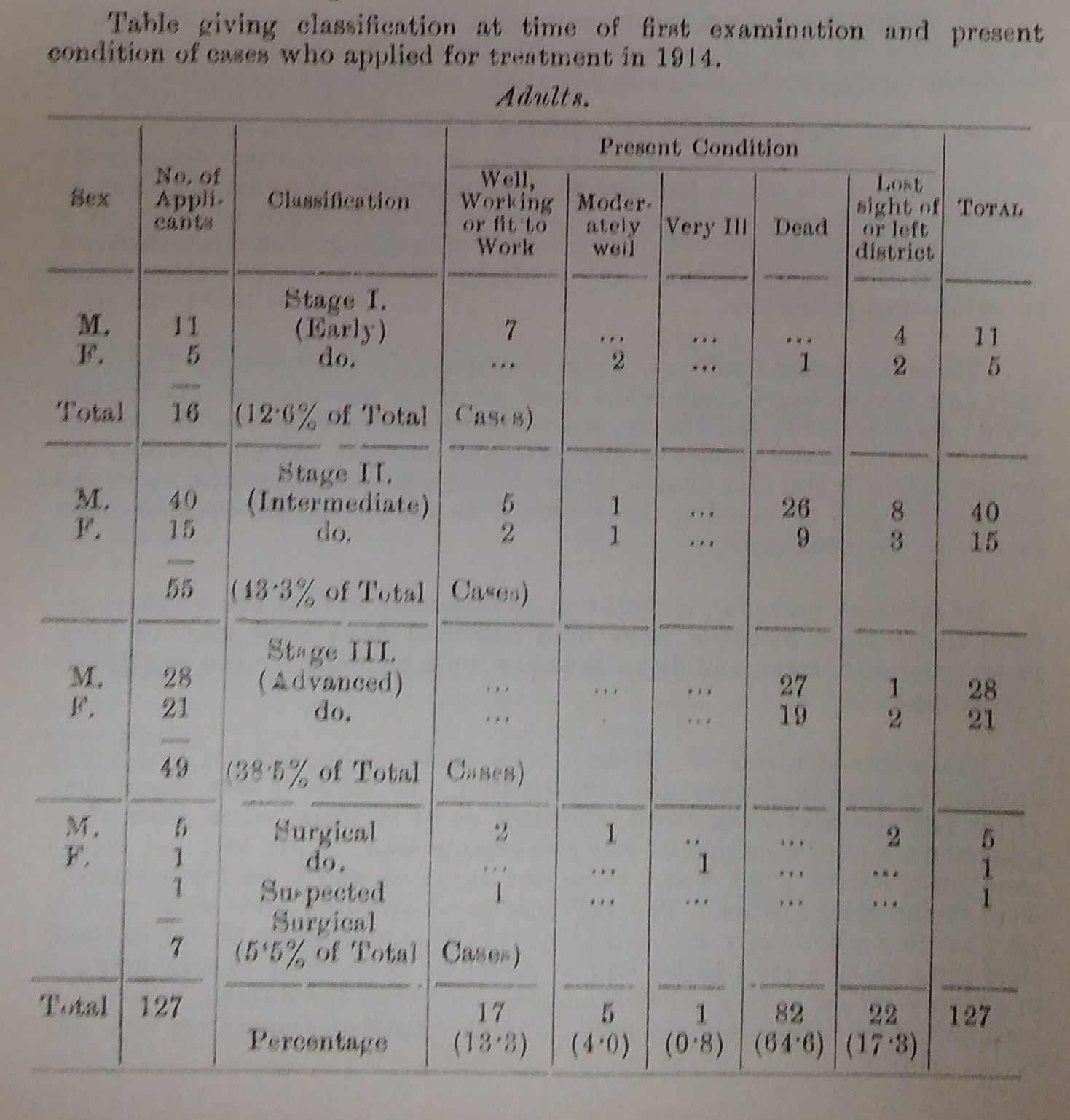

The Council felt provision of sanatoria was vital, providing uninsured patients with 10 beds at the private Barrasford Sanatorium, 9 at Stannington Sanatorium, and housed insured patients at other sanatoria as well. However many patients shortened their stay and returned to work to keep a wage. Likewise many tried to avoid going to see doctors in the early stages of TB as they feared taking time off work. The Medical Officer’s report for 1922 noted that many were coming to see the Tuberculosis Officer at the dispensary in the late stages of the disease. Above are tables showing what condition patients who applied for treatment for TB in 1914 were by 1922, and many had worsened or relapsed.

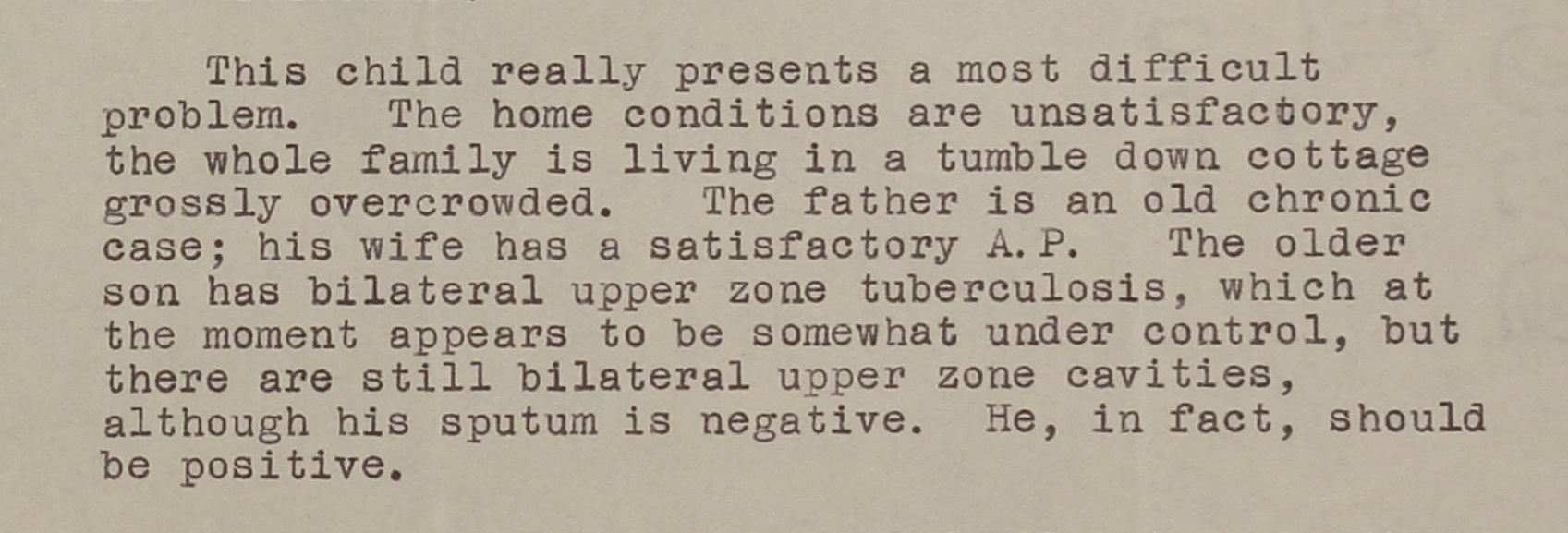

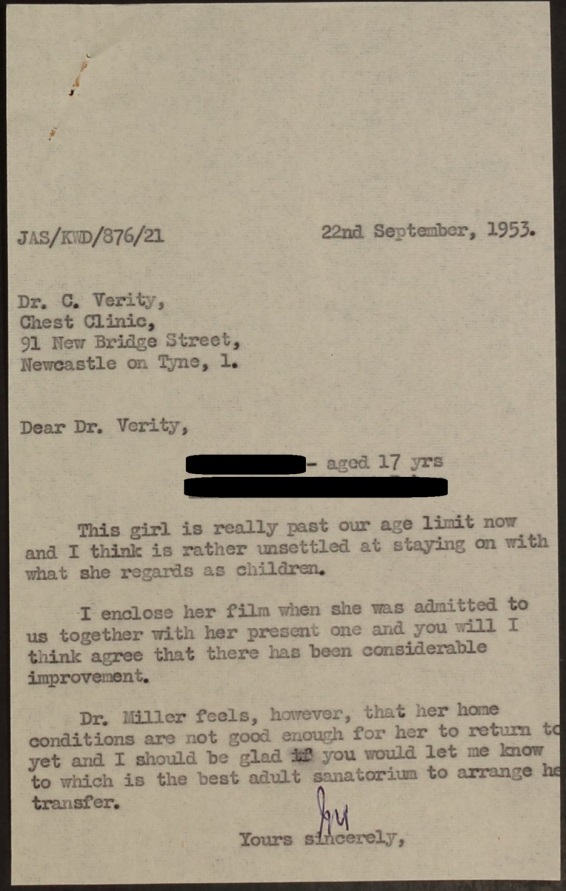

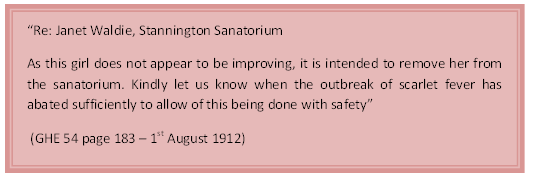

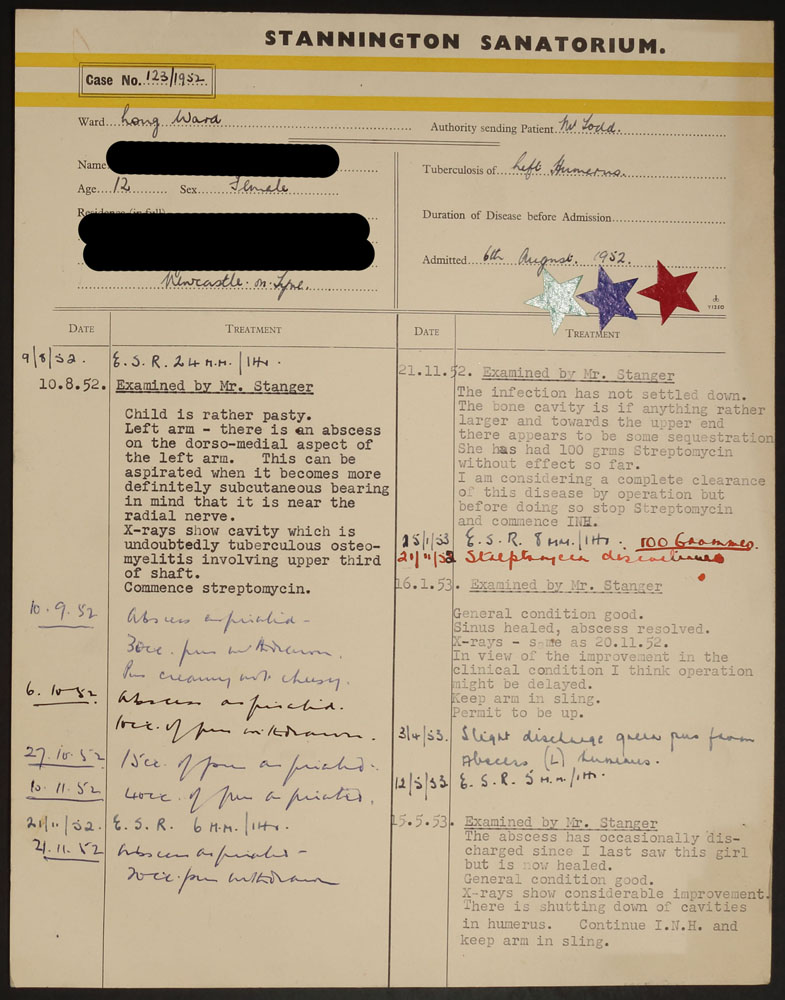

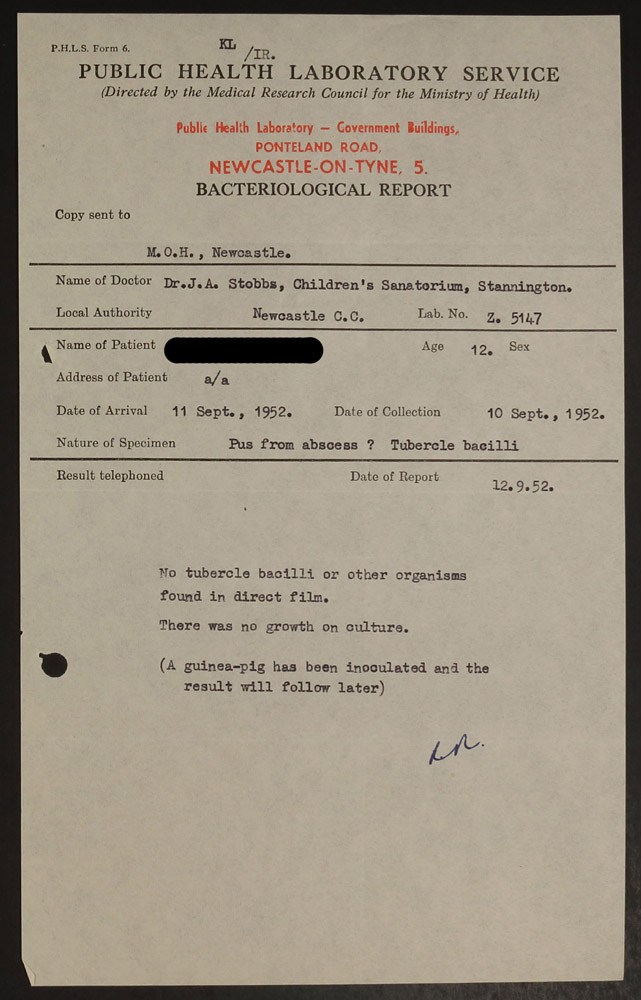

The Medical Officer also feared that once the patients had left the sanatorium, without further help the disease would return. The Stannington Sanatorium patient files echo this reluctance to return their patients to poor living accommodation. The majority of files give us some idea of the living arrangements in each child’s home, who the family members were and whether they had had TB. Below is part of a letter written in 1953 between Dr Miller and the Whickham Chest Clinic, in which he describes a patient’s home conditions:

The patient was kept at Stannington longer than medically necessary because of this. Another patient was only discharged when their family moved into a council house. Though the longer treatment received by the children at Stannington Sanatorium gave patients a much better recovery rate, improved home conditions were seen as essential to their long term improvement.

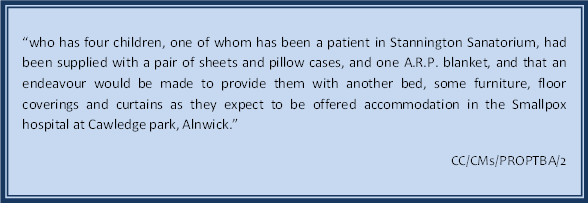

In 1944 the TB After-care Sub-committee was formed from the Public Health and Housing Committee. The central committee met quarterly, and worked with local sub-committees and an almoner to look after patients discharged from the sanatoria and new patients in the community. The county was divided up into 12 of these sub-comittees based on the then existing dispensary areas: Wallsend; Gosforth and Longbenton; Whitley and Monkseaton; Seaton Valley; Blyth; Ashington; Morpeth; Bedlington; Newburn; Hexham; Alnwick; and Berwick (CC/CMS/PROPTBA/1). Cases were referred to sub-committees by the Tuberculosis officer through the dispensary or local health visitor. Patients’ needs were assessed after a visit by the committee members, who would provide additional medical treatment such as nursing, free milk, extra food, training for employment, and financial assistance such as with rent. They also helped families move to better accommodation, provided travel expenses for patients and their families, clothing, shoes, and importantly, bedding ‘to enable patients and contacts to sleep apart and thus prevent the spread of infection’ (CC/CMS/PROPTBA/1). They provided equipment, from beds to back supports and bedpans, sputum mugs and even deckchairs. Gifts of drinking chocolate, tinned fruit, and magazines also went through the sub-committees. As at Stannington occupational therapy was important (see our previous blog post) with after-care patients crafting everything from embroidery to fishing flies, leatherwork, and even cabinets.

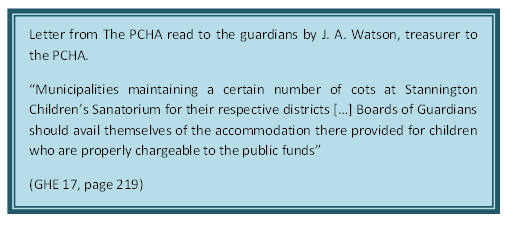

An important function was to refer patients for help with different organisations too, such as the British Legion, Ministry of labour, and the Poor Children’s Holiday Association. A patient assisted by the committee to become a shorthand typist was provided with holiday travel expenses by the ‘BBC Children’s fund for Cripples’, likely describing a forerunner of BBC Children in Need. The County Council paid the PCHA to board out children from homes with a Tuberculosis case, and many of these children likely went to Stannington.

There are several references to individual cases, including one lady:

During the Second World War mobile mass radiography became a huge boon to diagnosing the disease, with factories and workplaces often used as bases, and later mobile vans with their own generator operated in the community. They were used across the world and even reached Alaska by dog-sled. The County Council paid a shilling to the Newcastle local authority for each Northumberland case x-rayed with their machine. The County Council knew they would require an adaptable and economic mobile unit, but first used Newcastle Corporation’s unit at Ashington Colliery, where radiographs were taken from the 30th April 1947 (CC/CMS/PROPTB/2). By September that year 3,642 had attended in Ashington, with 23 referred to the Dispensary, and 1,780 attended the unit at Blyth, with 25 referred for treatment. Though the disease is by no means eradicated, improved housing conditions, the TB Vaccination, and early diagnosis with mass radiography made such a dramatic impact on the disease that sanatoria like Stannington were converted to other uses.

References:

Bynum, H., (2012) Spitting Blood: a history of Tuberculosis. Oxford: OUP

Taylor, J., (1988) England’s border county: a history of Northumberland county Council.