Burial of William Wandoe in Hexham, 1716

Reference: EP 148/5

Suggested age groups: KS2, KS3, KS4, Lifelong Learners

Subject areas: Black Presence, Transatlantic Slave Trade, Historical Sources

CONTEXT

Henry VIII ordered that parish registers of baptisms, marriages and burials be kept from 1538. Very few have survived from this date. Elizabeth I repeated her father’s order in 1558 and then ordered that parish registers be kept on parchment (rather than more vulnerable paper) in 1597. More registers survive from this date.

Parish registers are the most used sources at county archives. They are often used to trace researchers’ family history, but also contain information that can be useful to different types of researchers.

Most of the people of African descent living in this country during the eighteenth-century were men. Some historians* suggest that 80% of the Black population would have been male. This reflects the ratio of men to women forcibly transported from Africa to the West Indies and America.

Most of the men and women of African descent living in Britain at this time worked as servants. It is not always clear whether their official legal status was free or enslaved.

Eighteenth-century British newspapers contained advertisements for men, women and children who had run away from their enslavers. The adverts offer rewards for the return of the owners’ “property”. Many of these men and women are referred to as servants.

*See David Olusoga “Black and British: A Forgotten History”, London 2016. His discussion of the work of Felicity Nussbaum a scholar of the eighteen-century.

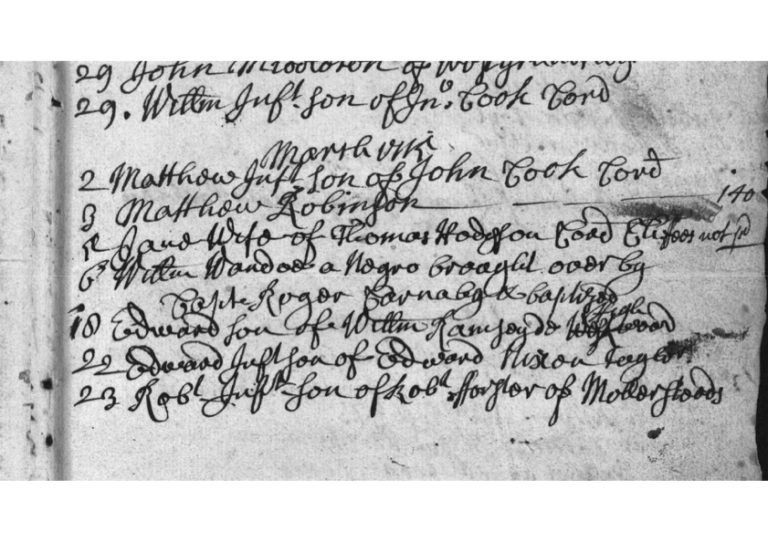

This is the burial entry for William Wandoe from the Hexham parish registers. It reads:

6 [March 1716] Willm Wandoe a negro brought over by Capt Roger Carnaby & baptized.

There is also part of an entry for William’s baptism, but the page is very fragile and hard to read. The date of the baptism is September 1714.

The registers also show that Roger Carnaby was buried on 7 April 1713. William received £10 from Carnaby’s will (see Border Ancestors website below). In the will William is referred to as Carnaby’s “man servant”.

It isn’t possible to say exactly when William came to England – “brought over” as it says in his burial entry. However, we do know that Carnaby made at least four voyages between 1702 and 1707 (see slavevoyages.org website below). All of these voyages followed the triangular route of the transatlantic slave trade. Two of his voyages (1702 and 1704) picked up enslaved people in Calabar (present-day Nigeria) and took them across the Atlantic to Maryland on the American mainland.

Wando is the name of a river in South Carolina, USA. The Wando flows into the Atlantic at Charleston, which was one of the biggest markets of enslaved people in America. Many slaving ships stopped off at Charleston after crossing the Atlantic; the brutal “Middle Passage”.

It could be suggested that William Wandoe was one of the Africans from Nigeria that Carnaby’s ship transported in 1702 or 1704. The name Wando suggests some connection with America and so it seems more likely that he was on one of the voyages that stopped off on the mainland, rather than in the West Indies.

The captain of slaving vessels made agreements with the investors before they set off on a voyage. There were usually several investors on each voyage to spread the risk. The captain of a voyage would negotiate a cash payment and a “privilege slave”- one of the enslaved people taken from Africa and transported on the ship. Once the ship arrived in the Caribbean or mainland America, the captain would usually sell his “privilege slave” and take the money. Occasionally, the captain would bring their “privilege slave” back to England with them as a servant.

It seems likely that William Wandoe was one of Carnaby’s “privilege slaves”.

Documents from the eighteenth-century regularly use language that is unacceptable. People of African descent were often called “negroes” as in this parish register.

ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 1

Background

This is the burial entry for William Wandoe from the Hexham parish registers. It reads:

6 [March 1716] Willm Wandoe a negro brought over by Capt Roger Carnaby & baptized.

There is also part of an entry for William’s baptism, but the page is very fragile and hard to read. The date of the baptism is September 1714.

The registers also show that Roger Carnaby was buried on 7 April 1713. William received £10 from Carnaby’s will (see Border Ancestors website below). In the will William is referred to as Carnaby’s “man servant”.

It isn’t possible to say exactly when William came to England – “brought over” as it says in his burial entry. However, we do know that Carnaby made at least four voyages between 1702 and 1707 (see slavevoyages.org website below). All of these voyages followed the triangular route of the transatlantic slave trade. Two of his voyages (1702 and 1704) picked up enslaved people in Calabar (present-day Nigeria) and took them across the Atlantic to Maryland on the American mainland.

SEE

See: Whose burial record is this?

See: When is the burial record from?

See: Where is the burial record from?

See: Who is Roger Carnaby?

See: When was William baptised?

See: How long after Carnaby’s death was William baptised?

THINK

Think: What does the term “brought over” imply?

Think: Why was William’s colour specified in the record?

Think: Is it necessary to include someone’s colour in their burial record? Think about this from several different viewpoints including the view of the historian.

Think: Why do you think Carnaby left £10 to William in his will?

Think: Why do you think William was baptised? Do you think this was his decision?

Think: Do you think William was freed upon Carnaby’s death?

Think: What was William’s status after Carnaby’s death?

DO

Do: Look at William Wandoe’s burial record without context for 10 seconds. What do you notice first? Feed back to the group.

Do: Look at William Wandoe’s burial record without context for one minute. Try to decipher it. What more do you understand about it now? Feed back to the group.

Do: Look at William Wandoe’s burial record without context for five minutes. Try to decipher a bit more and think about what we could infer from the record. Feed back to the group.

Do: After your final time feeding back to the group, write a short paragraph summarising what you have found out and inferred about William Wandoe from the record. Compare this to the context. How accurate was your understanding of the document?

Do: Imagine you are an archivist. Plan what your next steps would be to find out more about William and his life.

Do: Discuss whether you think Roger Carnaby should have been named in William’s burial record.

Do: Create a map tracking the routes that Carnaby’s slave voyages made.

Do: Create a map from the perspective of William making the journey from Africa to Britain via America. You could make this into a timeline.

Do: Discuss the name William Wandoe. When and why do you think he was given this name? Can you find the names of other enslaved people whose names may give an insight into where they were transported through?

Resources

ACTIVITY 2

Background

Most of the people of African descent living in this country during the eighteenth-century were men. Some historians* suggest that 80% of the Black population would have been male. This reflects the ratio of men to women forcibly transported from Africa to the West Indies and America.

Most of the men and women of African descent living in Britain at this time worked as servants. It is not always clear whether their official legal status was free or enslaved.

Eighteenth-century British newspapers contained advertisements for men, women and children who had run away from their enslavers. The adverts offer rewards for the return of the owners’ “property”. Many of these men and women are referred to as servants.

SEE

See: Which gender were most people of African descent living in Britain during the eighteenth-century?

See: What percentage of the Black population in Britain would have been male in the eighteenth-century?

See: What did most of the people of African descent living in Britain during this time work as?

See: What word is used to describe William’s colour in the record?

See: How was William’s position referred to in Carnaby’s will?

See: What are “privilege slaves”?

THINK

Think: Why do you think there was a much larger of men of African descent living in Britain than women?

Think: What can you infer from this statistic about the ratio of men and women forcibly transported from Africa?

Think: Why do you think more men were forcibly transported from Africa than women?

Think: Does the word servant imply someone is free or enslaved?

Think: Why do you think people in Britain ran away from their enslavers?

DO

Do: Discuss whether the terms “servant” and “property” contradict each other. What perception were the owners trying to give by using these terms?

Do: Research people of African descent working as servants in Britain during the eighteenth-century. Can you find evidence of what their roles included, how they were treated and what their living and working conditions were like? How did this differ from the experience of enslaved people in Britain?

Do: Discuss the use of the word “negro” at this time. Why was this term used? Compare it to the term “Blackamoor” used during the Tudor period and how the change in terms can reflect a change in attitudes.

Do: Discuss whether words used in the past, such as “negro”, were ever excusable or of they have always been unacceptable.

Do: Discuss how using terms such as “negro” emphasised “otherness” of people of African descent.

Do: Discuss which terms should be used today to refer to Black people and people of African descent.

Do: Research how phrases of African origin made their way into everyday British language during the eighteenth-century. Make a list of the words you find; how many are still used today? Use the English Heritage Black People in Late eighteenth-century Britain page to help you.

Resources

OTHER ONLINE RESOURCES

Black Presence

English Heritage website, page about people of African descent living in Britain during eighteenth-century: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/portchester-castle/history-and-stories/black-people-in-late-18th-century-britain/

The Guardian newspaper website, article by David Olusoga: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/aug/12/black-people-presence-in-british-history-for-centuries

BBC website, short film “Black to Life: Rethinking the Black Presence within British History”: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07dt1d3

BBC website, short films about individuals of African descent: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07dkx93/clips

BBC website, clip of “A Stich in Time” with Amber Butchart about Dido Elizabeth Belle: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p05v0nfq

Miranda Kauffman google drive of teaching resources for black Tudors: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Zl8QFafjchc2MzhntHE7zhY7uxyxL1-T?usp=sharing

Run Away Slaves in Britain website (University of Glasgow): https://www.runaways.gla.ac.uk/

Parish Registers

Northumberland Archives website, blog page about entries in the parish registers of people of African descent: https://northumberlandarchives.com/test/2020/10/13/black-presence-in-northumberland-parish-registers/

Roger Carnaby

Borders Ancestry website, page about the Carnaby family, including a copy of Roger Carnaby’s will: https://www.bordersancestry.com/blog/carnabys-of-todburn-the-missing-generation

Transatlantic Slave Trade

YouTube website, “Crash Course” video about the Atlantic Slave Trade: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dnV_MTFEGIY

Slave Voyages.org website, page with searchable database (you can search for name of captain – try Carnaby): https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

Language

Article from the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (BMJ online website), “Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or what? Labelling African origin populations in the health arena in the 21st century” by Charles Agyemang, Raj Bhopal, Marc Bruijnzeels: https://jech.bmj.com/content/59/12/1014

- Gabrielle Foreman, et al. “Writing about Slavery/Teaching About Slavery: This Might Help” community-sourced document, 14 May 2021: https://docs.google.com/document/u/1/d/1A4TEdDgYslX-hlKezLodMIM71My3KTN0zxRv0IQTOQs/mobilebasic

Money

The National Archives website, page with historic money convertor: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/

Bank of England website, page for historic prices calculator: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

“Privilege Slaves”

BBC Legacies website (no longer updated), page about the trade in enslaved people based in Bristol – mentions “privilege slaves”: http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/immig_emig/england/bristol/article_5.shtml