As part of the Stannington collection we have patient case files spanning the years 1939-1966 containing a wealth of medical and social information to support that found in the radiographs. The earlier files have a different format to the later ones owing to a change in the administration of patient records at Stannington which occurred in 1946. Up to 1946 the patient records take a much larger format and the patients were all allocated their own unique patient number based on their date of discharge, whereas from 1946 onwards standard sized paper files come into use with patient numbers being based on date of admission.

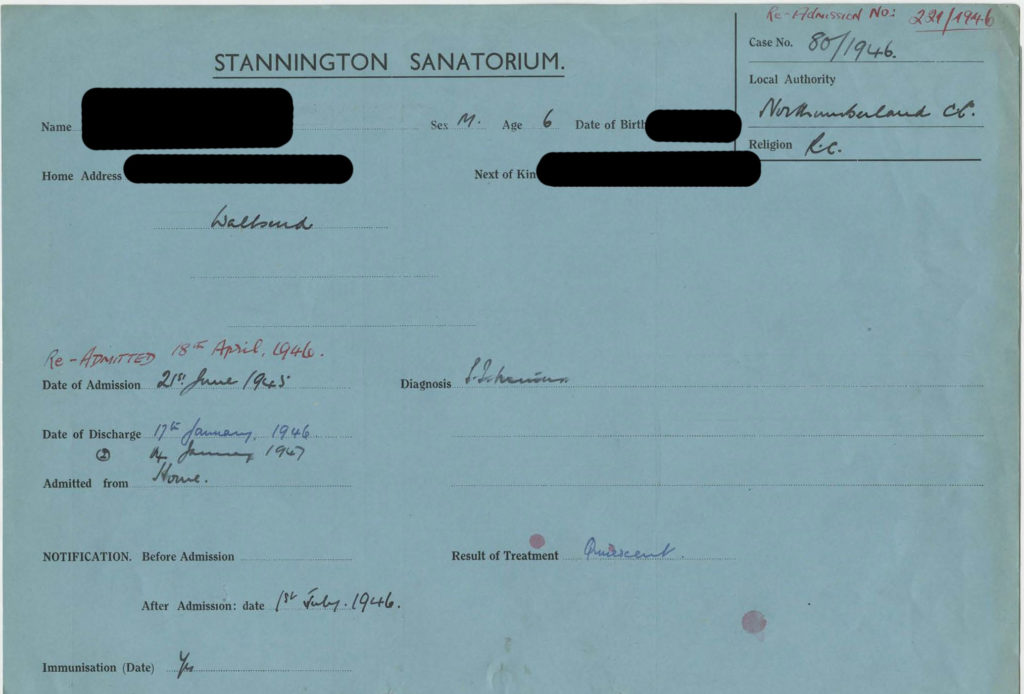

The above file is an example of one of the later files with the patient’s name redacted for confidentiality purposes. Three different colour files were used, each one indicating the type of tuberculosis the patient was suffering from. Blue files were used for sufferers of pulmonary TB, pink files for non-pulmonary TB, and finally green files for TB of the bones and joints. This image gives a good indication of the sort of information that can be found on the files, which is also indicative of the information we will be recording in our catalogue. The information featured in the catalogue for each patient will be as follows: patient number, date of admission, date of discharge, sex, age on admission, home town, diagnosis, result of treatment, where admitted from, the local authority sending them, and where applicable any re-admission numbers and dates.

To clarify some of the information given on the file, the date of immunisation refers to immunisation against diphtheria, not tuberculosis, as widespread vaccination against TB was not yet in place. As a contagious disease and a major concern for public health, all diagnosed cases of tuberculosis had to be made known to the local public health authorities, which is what the notification date refers to.

Each case of tuberculosis had to be classified according to centrally issued guidelines and this is often noted on the patient’s file under diagnosis. The first distinction made when classifying the disease is between pulmonary and non-pulmonary tuberculosis, with pulmonary including TB of the pleura and intrathoracic glands and any patient suffering from a combination of pulmonary and non-pulmonary TB would be classified as pulmonary. Cases of pulmonary TB could then be subdivided between TB minus and TB plus. Cases in which tubercle bacilli have never been found in the sputum or other pathology samples are classed as TB minus, as the above patient is. TB plus on the other hand applies to cases in which tubercle bacilli have at some point been found and is subdivided further into 3 groups; group 1 applying to cases with slight constitutional disturbances if any and limited physical signs, group 3 for cases showing profound constitutional disturbance or deterioration and with little or no prospect of recovery, and finally group 2 for all cases which cannot be placed within groups 1 or 3. Patients suffering from non-pulmonary tuberculosis would be classified according to the site of the lesion, for example, tuberculosis of the bones and joints, abdominal tuberculosis, tuberculosis of other organs, and tuberculosis of the peripheral glands.

There is also a space on each patient file to enter the result of treatment and there were also central guidelines covering this. Most patients leaving Stannington are deemed to be ‘quiescent’, meaning that they have no signs or symptoms of tuberculous disease and any sputum is free of tubercle bacilli. A patient’s condition could also be classed as ‘arrested’ by which it is meant that in pulmonary cases the disease has been quiescent for at least two years and in non-pulmonary cases it is quiescent and there is no reason to believe it will recur. And finally, a patient could be considered to be ‘recovered’ if the disease had been arrested for at least three years.

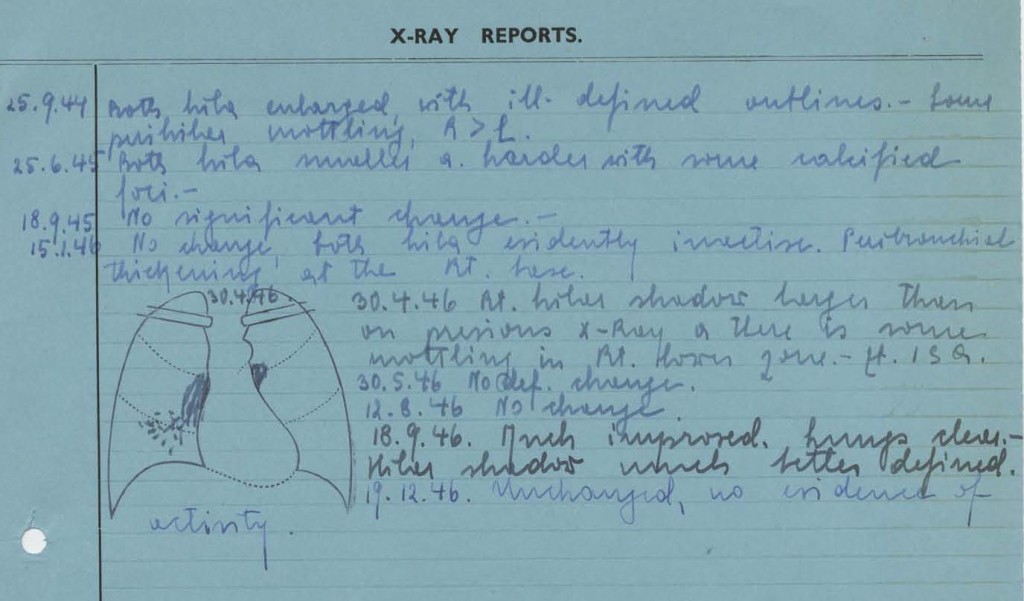

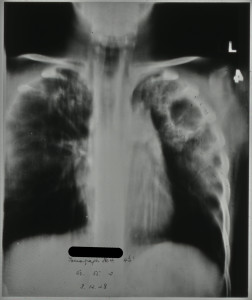

The information that you can expect to find within the patient records does vary from patient to patient but generally includes data on other family members, living conditions, medical history, temperature charts, x-ray reports, pathology reports, details of progress, and any correspondence with family members or local authorities. The correspondence contained within the files can give a fascinating insight into social problems and the impact tuberculosis could have on families at the time adding an extra dimension to the medical information that we expect to find. The image below is an example of the x-ray reports that can be found in the back of some of the files; it is quite common for files dating from the mid-1940s to find small diagrams of what was seen in the x-rays also.

[HOSP/STAN/7/1/1/1587]