Whilst trawling through newspaper articles for references to William Procter the younger and his future wife Isabella Young Gilchrist to include in our recent blog we uncovered a national scandal involving the Gilchrist family, bigamy, adultery and divorce. This research shaped our second blog in the “The Meeting, Marriage and Parting of Ways” series, which uses the Dickson, Archer and Thorp papers to open up and explore the intimate relationships of nineteenth century Northumbrians.

A National Scandal

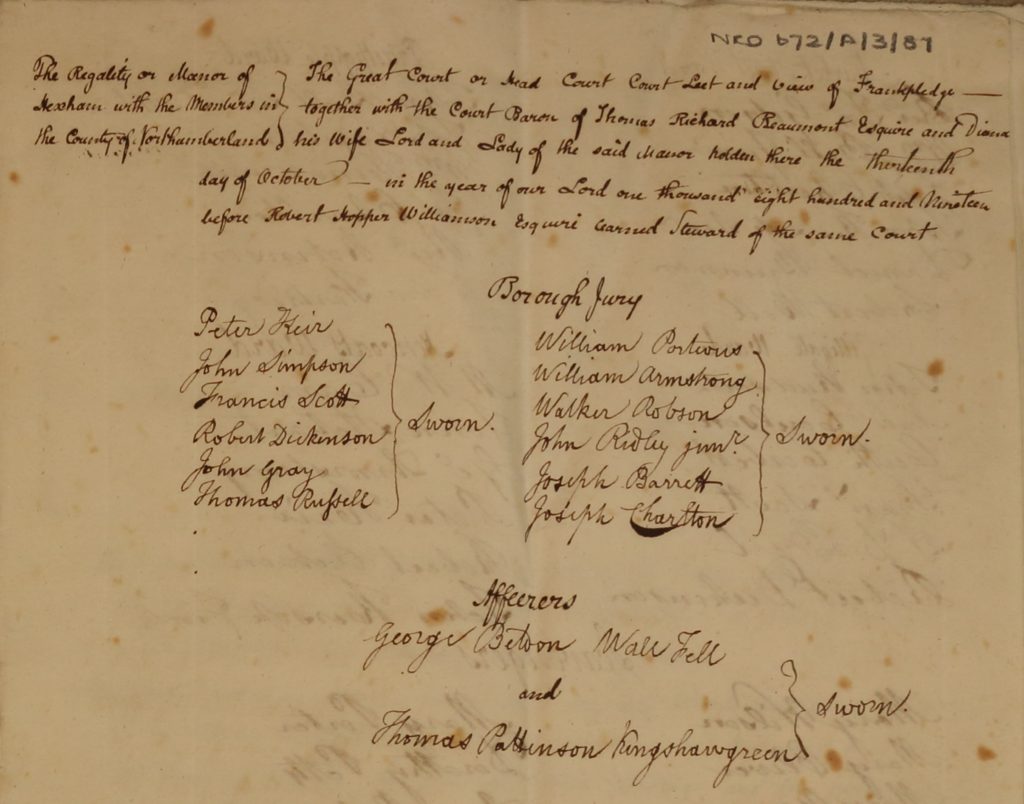

The scandal which awarded the Gilchrist family national notoriety related to the bigamous marriage of Isabella’s younger sister, Georgina, and a Mr William Henry Stainthorpe. William Henry was born to John and Mary Stainthorpe and christened in Hexham on the 15th September 1839. Like his father before him William Henry pursued a legal career, eventually becoming a solicitor. Georgina, sometimes referred to as Georgine in contemporary documents, was the daughter of Thomas and Margaret Gilchrist. Her father had been the Town Clerk for Berwick Upon Tweed and, having been born in 1841, she was the youngest of six daughters.

It is likely that William Henry and Georgina were first introduced whilst William was serving his articles in Berwick Upon Tweed, under the instruction of a Mr Sanderson, in the late 1850s. It is also likely that William Henry was known to Georgina’s older brother Thomas Gilchrist, who was also operating as a solicitor in Northumberland at the time.

Youthful Love

From the very start the young couple experienced opposition to their relationship. Georgina’s mother was initially against the courtship as she believed her daughter was too young to be engaged. But only a few years later on the 3rd December 1862, when Georgina was of age, the couple defied their families and married at St Clement Danes in London. Georgina’s sister, Isabella Young Gilchrist, witnessed the ceremony and subsequently testified to the legitimacy of the marriage in front of a Liverpudlian court.

A “Two-Wife” Man

Following the ceremony at St Clement Danes the couple lived together in London until October 1863 when Georgina fell pregnant and returned to her mother in Berwick Upon Tweed. Whilst retrospectively reporting on the scandal The Berwick Journal noted that the move was not caused by;

“any disagreement or any apparent want of affection, but his inability to support her; and she herself thought it would be better for her to live with her mother until such times he should be in a position to take her to his house.”

Their daughter, Mary Harriet Georgina Stainthorpe, was born on the 27th February 1864. Georgina noted in her divorce documents that she heard less and less from her husband upon her return to Berwick and, following the birth of their daughter, their communication ceased altogether. At the same time, according to subsequent news reports, William Henry had made the acquaintance of Mary Louisa Allin whilst working in Plymouth. He wrote letters to Miss Allin and her mother informing them of his intention to court, and subsequently marry, Mary. In these letters he made no reference to, or disclosed, his actual marital status.

In 1867 William Henry moved to Liverpool to take up the position of managing clerk in a solicitors firm. He then returned to Plymouth to bigamously make Mary his wife on the 20th April 1867 at Charles’ Church. The newly married couple then moved to Liverpool and set up home in no. 34 Egerton Street. William Henry had now completely deserted his first wife with a new baby and no money, but his lies were about to catch him out…

Lies in Court

Towards the end of 1867 Dr Clay, husband to one of Georgina’s sisters, was also living in Plymouth. He had heard about Mary Allin’s recent marriage through his friend Captain Julian. The Captain was married to Mary’s sister and both men became suspicious when they realised a series of similarities between their respective brother-in-law’s. Both men shared the same name, had the same occupation and appeared to match the same description. The suspicious men therefore took a letter, signed by William Henry, and compared it to his signature in the London marriage register.

Upon finding a likeness between the handwriting the men raised the alarm and both wives were instantly informed of the truth. William Henry was taken into custody to stand before a Liverpudlian court charged with bigamy. During the court case a Mr Cobb provided the defence, whilst Mr Samuel appeared for the prosecution.

The case was great fodder for the local and national press. Court reporters described William Henry as being;

“fashionably attired; … about 26 or 27 years of age, and a person of good appearance and address. He seemed greatly agitated, and was evidently affected at the degrading position in which he was placed.”

Mrs Isabella Proctor, previously Young Gilchrist, was sworn as a key witness in court. She attested to a number of damning claims against William Henry, thus proving his infidelity;

“It was there (Berwick-Upon-Tweed – her hometown) I became acquainted with the prisoner. I think it was the winter of 1860. To the best of my knowledge it was at Berwick-on-Tweed that he became acquainted with my sister. Between that time and the spring of 1860 he was introduced to our family, and visited at my mother’s house. It was about that time that he became engaged to my sister. She was twenty years of age at the time. In 1862 I received an invitation from my mother to go to Ashford, near Windsor, to London, to be present at the marriage of my sister… She was married to the prisoner on the 3rd December 1862 at St Clement Dane. I signed the register as one of the witnesses. My sister is still alive. I saw her yesterday morning. She is residing in Berwick-on-Tweed with my mother. She has a child living with her…. I always heard my sister speak in strong terms of affection for her husband.”

Several further witnesses were also called to stand alongside Isabella; including the policeman and detective who had arrested William Henry, a Berwick-based vicar and Captain Julian. Mr Cobb tried to argue that the first marriage had ended in mutual separation, and that his client knew nothing of little Mary’s birth or the witnesses stood before him. Yet the prosecution sarcastically remarked that “he cared to know nothing at all about it.”

William was refused bail and the judge remarked that it was a “very heartless case.” He was subsequently sentenced to 12 months imprisonment for his crime.

Divorce and Forgiveness

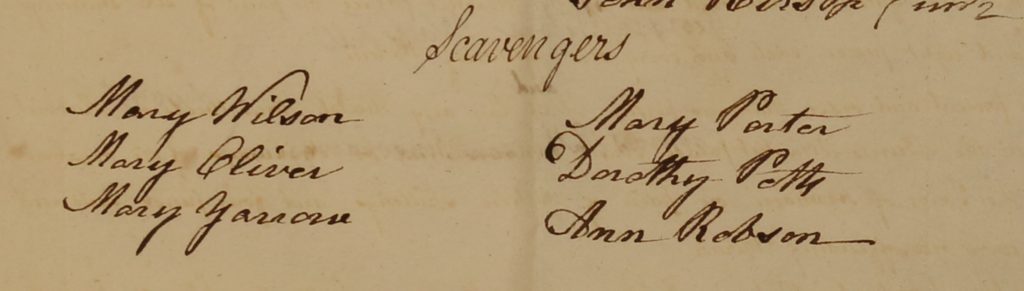

In light of the scandal Georgina chose to pursue a divorce. To receive a divorce Victorian women had to provide a reason; with bigamy and adultery widely accepted as grounds for separation. But reason alone was not enough, as proof also had to be submitted before the court. This was often off-putting for women who did not wish their personal business to become public scandal. But Georgina’s marriage, and her husband’s indiscretions, had already become national news and she had the evidence of a court case to promote her argument. Thus, following the case, Georgina delivered a divorce petition to the courts providing both adultery and bigamy as her reasoning. She also requested to maintain sole custody over their child. Her petition and request was granted by the court at the end of 1867.

It would have been understandable for Mary Louisa to have also walked away from her relationship with William Henry. Being his second “wife” the marriage was never legally binding. But she stayed with him and, following his release from gaol, she re-married him on September 28th 1869 in Kentish Town.

The Stainthorpe’s moved back to Northumberland, and in 1871 can be found living in William’s home town of Hexham. During this period William is listed as a solicitor awaiting a position or, in layman’s terms, unemployed. In September 1872 the couple had a son, Percival John, in the parish of Tynemouth but the child died less than a year later. What happened to the couple after this is a mystery, but we do know that William’s first child, Mary, chose to retain his surname before marrying in 1891.

We would like to thank our volunteers who have tirelessly worked to transcribe the original marriage settlements found within the Dickson, Archer and Thorp Collection.