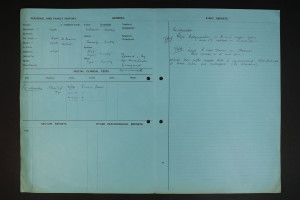

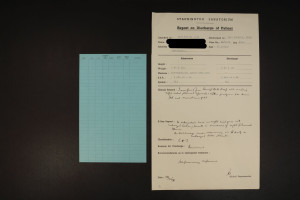

The Court Calendar for the Easter Quarter Sessions held at the Moot Hall, Newcastle upon Tyne on 10th April 1890 lists that appearing at court that day was Arthur Stanhope .He was also known by the names of Arthur Reed, Arthur Wilson and Albert Edward Newton. The Calendar gives his age as 34 years, his trade as a decorator and records that he was only able to read and write imperfectly. He pleaded Guilty to an offence of Obtaining Money by False Pretences and was sentenced to twelve months.

The brief for the prosecution states that the prisoner “seems to be well acquainted with the district” and has been “exciting sympathy on account of his having lost an eye in September last and him being on his way to Edinburgh Infirmary”. He is also described as an “old offender” having been convicted at the Northumberland Easter Quarter Sessions in April 1885 “as well as at other places previously”. For this offence of Obtaining Money by False Pretences which was committed at Rock, Northumberland he was sentenced to six months.

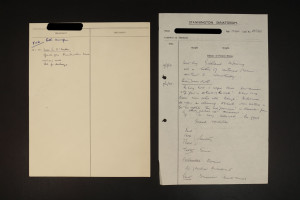

From correspondence between Superintendent John Kennedy of Wooler and Mr Robert Archer found with the case papers Mr Archer had also dealt with the 1885 case.

His list of previous convictions shows his first conviction to have been at the age of 28 in May 1884 when he was sentenced to 3 months for obtaining money by forging letters. As his trade was given as a decorator one wonders if his eye sight had now become so bad that he had to resort to fraudulent means in order to get money to survive. Or perhaps this was the first time he had been caught. Other convictions followed for fraud and falsehood involving money or goods and were committed in the Scottish Borders, namely Edinburgh, Dunns, Jedburgh and Selkirk.

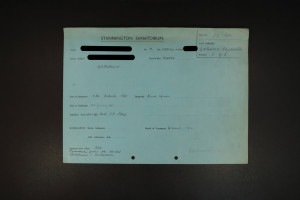

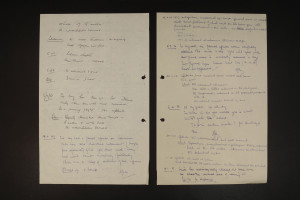

In the 1890 case the arresting officer was a Pc Thomas Robson stationed at Lowick. On the 20th March from information received he was on the lookout for Stanhope and tracked him down to a lodging house in Lowick. When spoken to he gave his occupation as a piano tuner and said he had got a job at Barmoor Castle. After further enquiries Pc Robson found this to be false. Stanhope was arrested on the 22 March. He was charged two days later. Pc. Robson states Stanhope said that once he was clear of the case he would leave the county “and the next time you hear of me I will be making an honest living”.

One can only speculate as to how Stanhope came to loose an eye. In his statement Superintendent Rutherford states Stanhope “came into my custody at Alnwick on a similar charge between 22nd and 28 March 1885 and “at that time the prisoner was without the left eye” this being five years before this offence. One of his victims, Mrs Edith Maria Sitwell of Barmoor says in her disposition that Stanhope said he had been seen by Dr Argyll Robertson at the Edinburgh Infirmary and this may well have been true. Research has shown that he was the Senior Surgeon there from 1870 to 1897 specialising in eye disease and developed a procedure known as the Argyll Robertson Pupil which was used in the diagnosis of syphilis.

Stanhope was arrested after his visit to Mrs Sitwell. She was a widow and gave him 12/-. He is alleged to have asked for 11/- to get “New clothes to make him tidy to go into the Edinburgh Infirmary” Her generosity may have been swayed by Stanhopes referral to her neighbours a Mr Forster of Lowick who had “told him to come” and Colonel Hill of Low Lynn who he said had given him one pound. Colonel Hill had not believed his story and sent him away and Mr Forster had given him money. When arrested Stanhope was in possession of 6/-in silver.

Stanhope was also able to obtain money and in one case clothing from two Justices of the Peace for the County. George Pringle Hughes of Middleton Hall Wooler who became High Sheriff of the County in 1891 and Edward Collingwood the younger of Lilburn Tower. He was given 5/- by Hughes and clothes and 5/- by Collingwood. He used the same story namely he needed to get to Edinburgh for medical attention.

In an age when state support for persons unable to work due to illness or disability was minimal it would become necessary to either live on your wits, resort to begging or become an inmate of the workhouse. Stanhope seems to have chosen to live on his wits.

Stanhope states on two occasions that he is a Piano Tuner. This was a common occupation for people of limited sight in the nineteenth century and was helped by the demand for pianofortes as they were called by the well to do. Some were apprenticed to piano manufacturers but others may have seen it as an opportunity to make easy money. All that would be needed were a few tools and a teach yourself book. As Stanhope seems to have been able to convince upstanding members of the County of his intention to seek medical assistance, perhaps he perfected his skills of persuasion whilst visiting their houses.

Habitual Offenders were also receiving harsher sentences in 1890, and it may be that Stanhope was made an example of. After all he had managed to “con” a widow, a Justice of the Peace and a future High Sheriff of Northumberland out of substantial amounts of money.

Bibliography:

A History of Piano Tuning by Gill Green M.A

Wikipedia: Dr Douglas Argyll Robertson

We would like to thank the volunteer who kindly produced this blog piece; especially for their meticulous research of these documents and transcription of its contents.