The Poor and the Law

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries local parishes were made responsible for the care of paupers within their jurisdiction. This care was given in the form of poor relief legislated by a series of ‘Poor Laws;’ the most notable being the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. The concept of poor relief was a controversial one, attracting numerous critics. One its major flaws related to the notion of ‘settlement.’ Parishes naturally resented paying for paupers whom had originated beyond their jurisdiction, and would often try to forcibly return them to their ‘home’ parishes. Yet the fluid nature of society, especially during the industrial revolution, made it increasingly hard to prove where a “pauper” should be placed. Thus solicitors, such as the Dickson, Archer and Thorp firm, were often called upon to resolve settlement disputes.

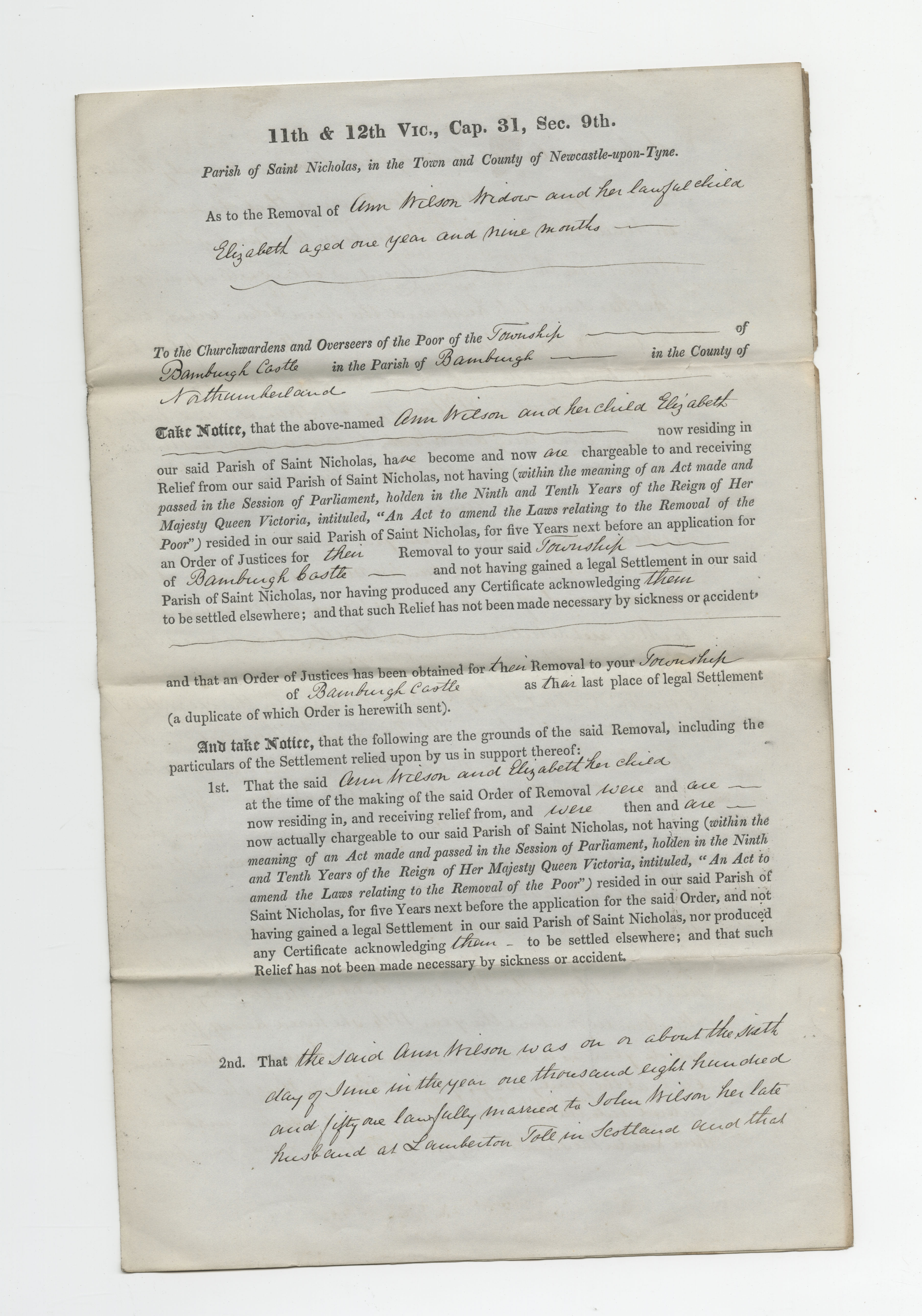

This exact issue arose in September 1853 when two Overseers of the Poor from the parish of Saint Nicholas, situated within Newcastle Upon Tyne, began legal proceedings to forcibly remove two “paupers” from their jurisdiction. These Overseers signed themselves in the removal order as Sir John Fife and William Armstrong. The order directed the “paupers” to be moved into the northern parish of Bamburgh. Although it is not clear from archival documents as to why Bamburgh was chosen it is perhaps telling that Bamburgh’s own Overseers of the Poor fiercely disputed the removal order and so employed the legal aid of Dickson, Archer and Thorp.

Widowed Paupers

The two “paupers” facing removal from the parish of Saint Nicholas in September 1853 were the widow Ann Wilson, aged just 25, and her daughter Elizabeth, aged about two years. Sending widows away from a parish of settlement, previously adopted by their deceased spouses, was a common occurrence in nineteenth century Northumberland. The process often caused heart-breaking social and economic turmoil, as vulnerable women were removed from established networks of friends and family and placed in often unfamiliar areas without obvious employment or emotional support.

It is therefore unsurprising that the potential move was also sternly opposed by Ann herself. Ann had already faced the stigma of possibly welcoming a child out of wedlock, braved her employer’s wrath to elope with her lover and tragically endured early widowhood – clearly she was not a woman who would be moved easily. Thus, whilst her experience of parish poor relief could be deemed atypical of a nineteenth century Northumbrian widow, her situation was far more complex and it made fighting the order a matter of survival and reputation.

Young Lovers

Ann was the daughter of a sailor, named in legal documents as Henry Pryle Gibson. He was recorded in ejectment proceedings as living near Forth Banks, close to Newcastle’s Quayside, but in Ann’s personal testimony he seems to have had little to do with her life.

Instead Ann had spent the majority of her youth working as a domestic servant. In this occupation she had spent almost 3 years living in Newton on the Moor whilst working for the publican-come-blacksmith Mr Wall. In her testimony, given to prove she had been legally married to her deceased husband, she tenderly recalled how it was during her first few weeks in Newton on the Moor that she met the colliery engine-man James Wilson.

The young couple began a three year courtship which reached a decisive point when Ann became pregnant in the beginning of 1851. To have maintained a child out of wedlock would have put great financial pressure and reputational shame upon Ann; probably forcing her to give up domestic employment and seek the support of parish organisations. Thus, probably to avoid moral judgement, the young couple decided to elope to the Scottish borders and resolve their situation legally.

The Legality of Love

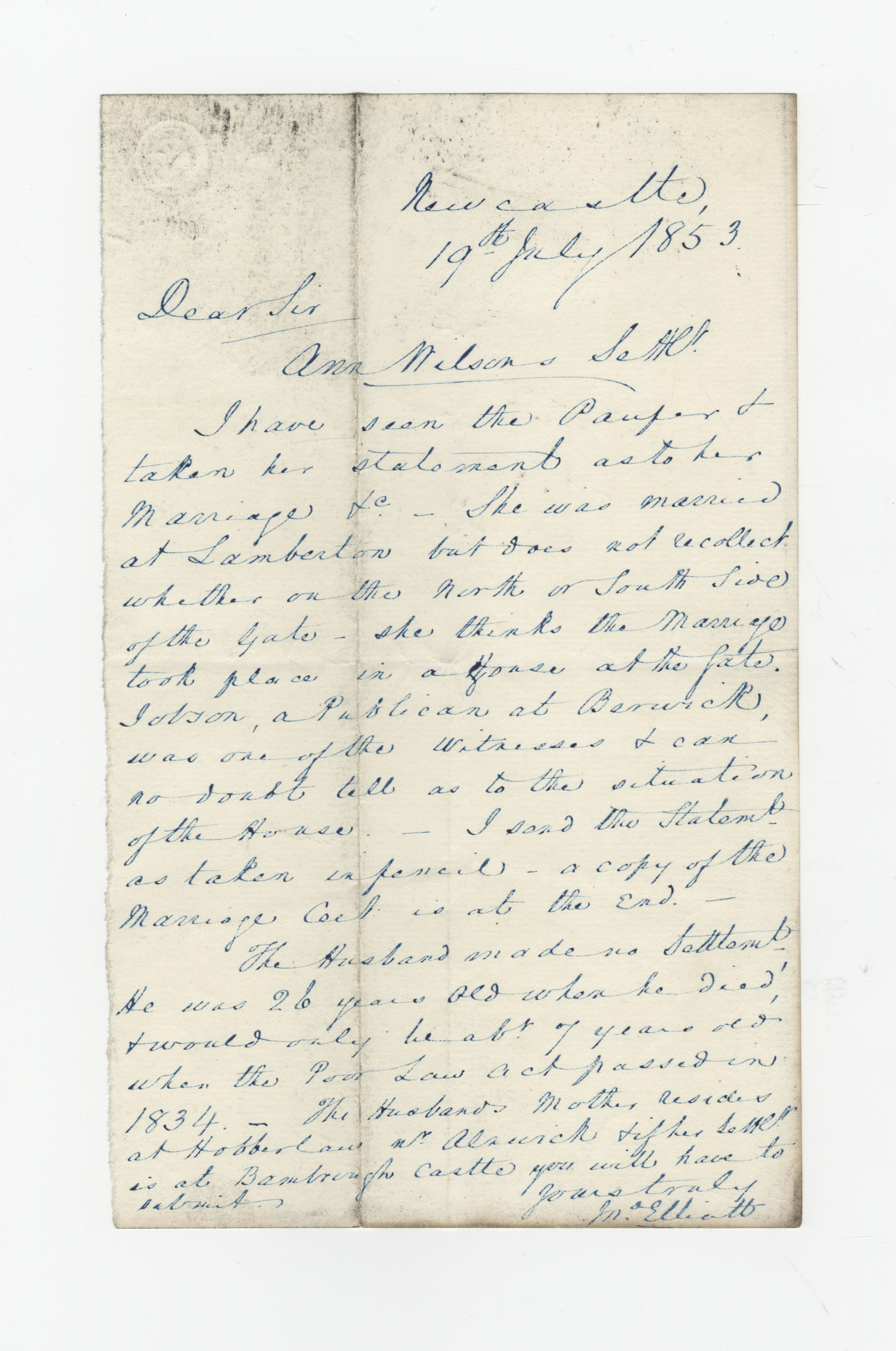

Marriages conducted by eloping couples on the border were clandestine in the eyes of the Church, this made them notoriously hard to prove in retrospect. Ann’s account of her elopement is lengthy, witty and fast-paced. It was recorded verbatim by the solicitors and had been carefully crafted to prove the legality of her marriage and, in turn, the legitimacy of Elizabeth – two facts which the Newcastle Overseers had questioned. Being a legal widow, and having a legitimate child, would have put Ann in a much stronger position to fight the parish removal order and lift the reputational slur the men of Saint Nicholas’ parish had placed on her. Ann’s account was also verified by a number of witnesses including her mother-in-law (even though her testimony infers that she may not have wholly approved of her new daughter-in-law.)

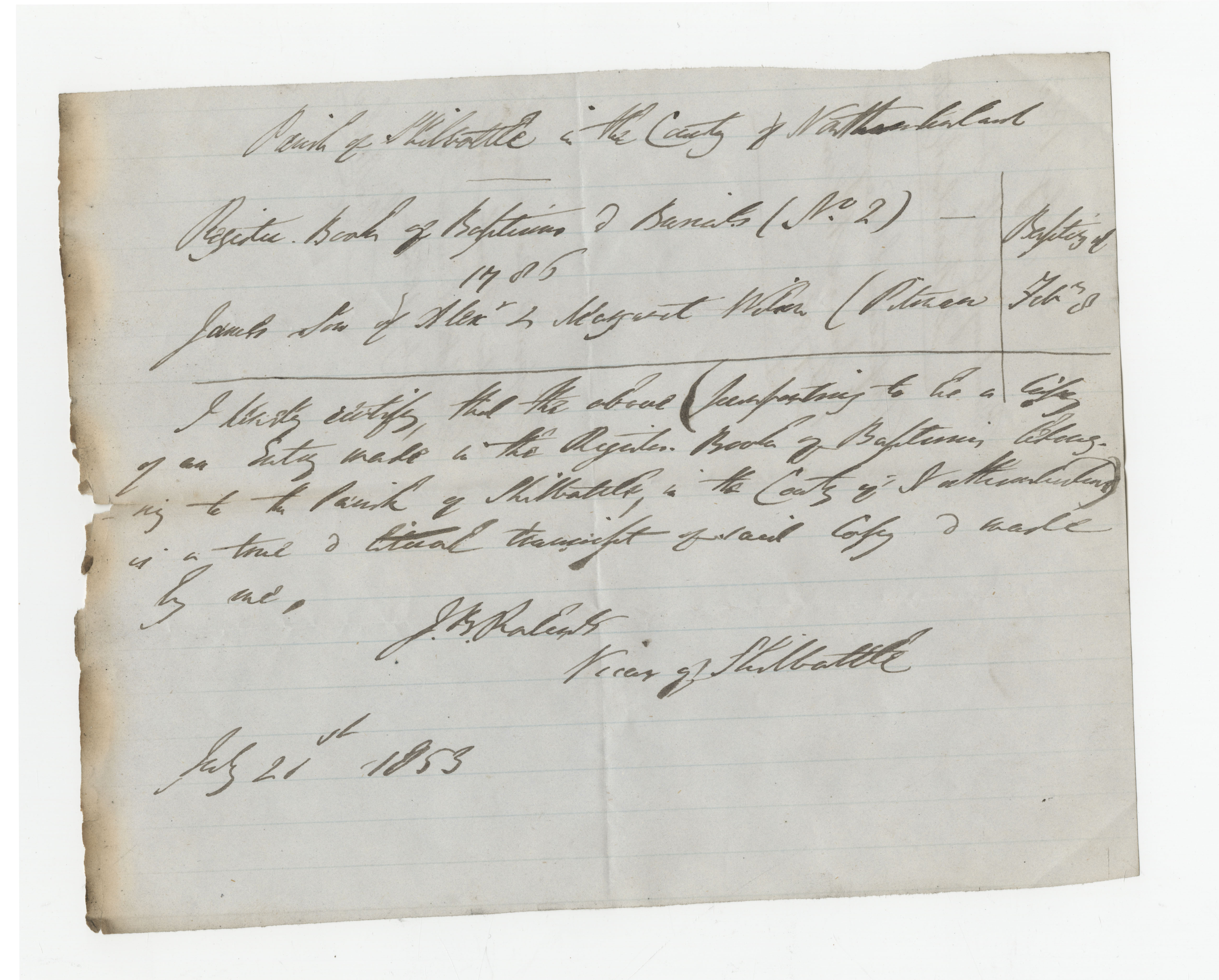

According to these accounts Ann and James eloped to the Scottish border on the 6th June 1851, travelling via train from Newcastle to Berwick. Once at Tweedmouth Station they met with the man who was to marry them; Anderson Sommerville. Sommerville first took the lovers by horse drawn carriage to a public house in search of witnesses; here they met George Dobson and George Davison. The latter was a soldier tasked with recruiting in Berwick that day. The group then moved onto the Lamberton toll booth to conduct the ceremony.

The Lamberton toll house was a popular place for clandestine marriages. One of Lamberton’s previous toll keepers, John Foster, had even received lifetime banishment from Scotland for conducting clandestine marriages on his land in 1818. This punishment had little effect though, as Foster primarily lived in England and he would often ignore the notice anyway.

Within the toll house the Wilson’s were taken to a room with a table, bottle of whiskey and a prayer book. It was in this room where they exchanged their vows and signed the relevant documentation. After the brief ceremony all five drank a toast of whiskey to the marriage’s prosperity which was, unfortunately, to be short-lived.

Hanover Street and a New Start

Ann clearly thought she had embarked upon a whole new, exciting life following her elopement. When the couple returned to Northumberland it would appear James returned to Newton on the Moor, to tie up the loose ends left behind by their hasty departure, he then followed Ann down to Newcastle where she had found them a home in the city’s Hanover Street.

It was here that Ann gave birth to their daughter Elizabeth, on the 28th September 1851. But sadly, around the same time, James died following a short illness.

James’ death left Ann with a young child to feed and care for. It was during this painful, and probably traumatic, experience she found herself seeking poor relief from parish officials. Evidence also suggests she was possibly forced out of her new home. These circumstances therefore assembled to bring her to the attention of senior parish officials, whom questioned her marriage and associated right to remain in the area, and set in motion the removal order.

A Legal Success

Proving Ann Wilson’s right to settle in Saint Nicholas’ parish was dependent upon her having been legally married to her husband, however this was difficult to evidence due to the secret nature of their union. Nonetheless, through tireless county and cross-border investigation, solicitors at the Dickson, Archer and Thorp practice were able to successfully evidence an appeal against the removal order on behalf of Bamburgh’s Overseers of the Poor and prove the authenticity of a small marriage certificate, given to Ann on her wedding day. Officials from the parish of Saint Nicholas eventually revoked their removal order and Ann and Elizabeth appear to have found somewhere within Newcastle to stay.

Ann had asserted her right to remain within the Newcastle Parish, but it is unlikely she would have had the tools to fight the removal order on her own had she not also had the support of Bamburgh’s parish officials. Hence this is a story of two parties working simultaneously with the solicitors – if only for their own gains.

A final triumph for the unyielding Ann, and an appropriate end to this blog, potentially occurred on the 7th October 1854. When an Elizabeth Wilson, recorded as being the daughter of an ‘Ann Wilson” and born towards the end of 1851, was christened at Saint Nicholas Cathedral in Newcastle.