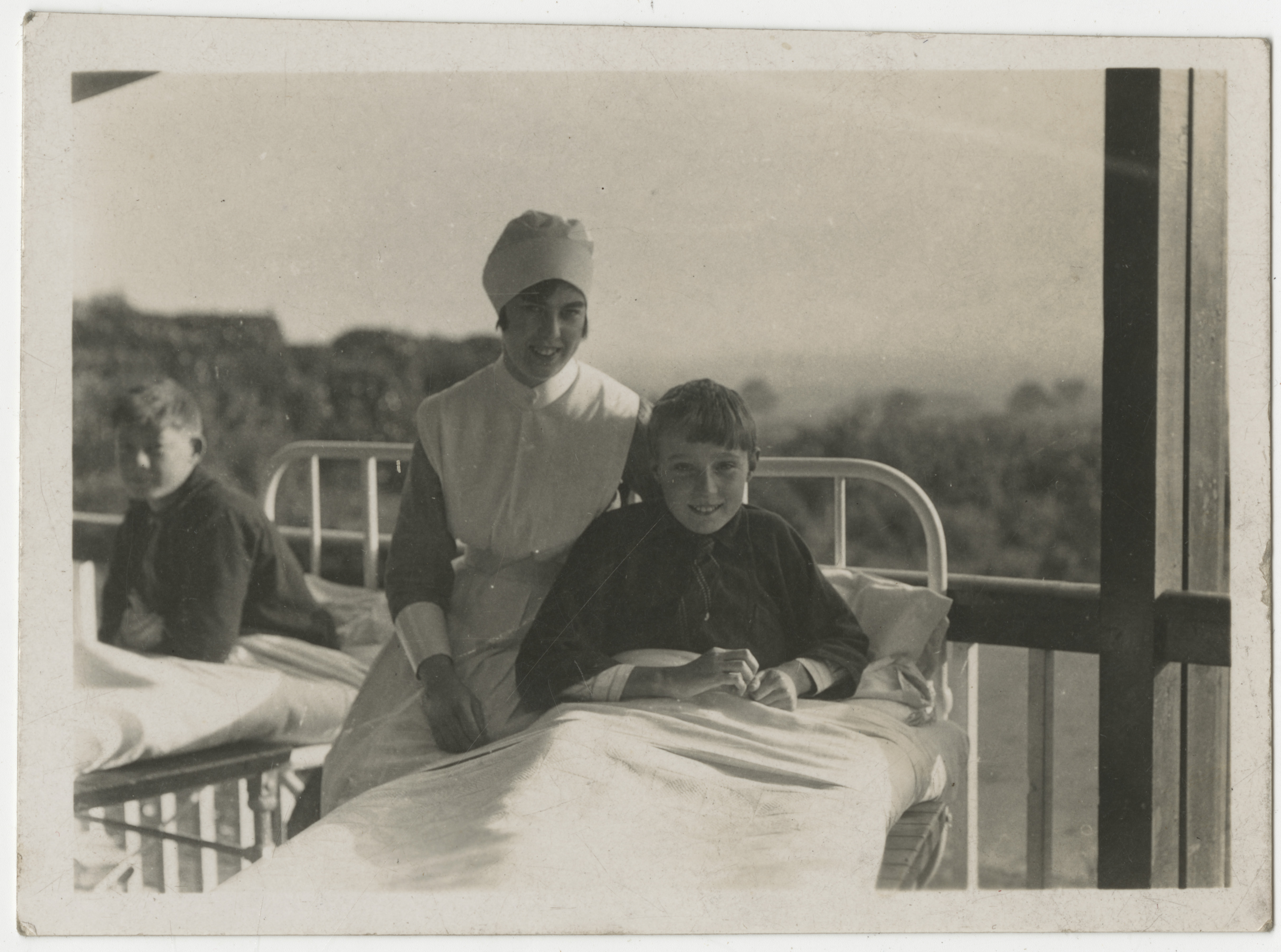

Today is International Nurses’ day, which celebrates the work and contribution of nurses to society and takes place on the birthday of Florence Nightingale. We thought we would select a few images and documents to give us an insight into the sanatorium nurses’ lives at Stannington. Our online exhibition has already looked a little at the lives of the nurses, especially in the early years, so we thought we would look at some of what our collections reveal about their lives and surroundings.

At many hospitals accommodation would be provided for staff. Florence Nightingale highlighted the importance of space for staff as nurses had formerly slept on the wards, and nurses’ homes became used from the 1870s. The Nurses’ Home at Stannington Sanatorium, constructed in 1926, is sadly an enigma as we have no layout of the interior. If it was built like others the nursing hierarchy would have been preserved in the architecture. Sisters often had their rooms at the end of corridors so they kept an unofficial eye on younger staff, and matrons’ rooms were often near the main door, overlooking staff and visitors as they came and went. We know the Nurses’ Home at Stannington Sanatorium was large to incorporate further growth in the number of nurses required. However an excellent insight into the building comes from the war years, when a number of documents in the Annual Report for 1946 (HOSP/STAN/2/1/2) relate to the curtains, carpets and furnishings of rooms as they were moved from Stannington to the Hexham Hydro and back again.

An inventory of furniture in rooms made by Miss Martindale on the 28th August 1944, ahead of the transfer back from Hexham Hydro, lists the contents of the doctor’s and matron’s rooms. This gives quite a detailed view of the Matron’s room:

(13) Matron’s bedroom, Stannington – wardrobe and dressing chest in Matron’s room at Hexham. Bed wanted for matron’s bedroom at Stannington. Keep a Hydro bed for this purpose.

(14)Rose-pink long curtains and pink carpet from Matron’s sitting rooms at Stannington are in store in the attic at Hexham. Note: – Keep carpet in Matron’s room at Hexham for use at Stannington (Carpet extra good quality).

(15) Matron’s spare bedroom at Stannington. Bedroom suite, wardrobe, dressing table and bed in one of the Sister’s bedrooms at Hexham.

The Assistant Matron’s room had a simpler layout of ‘1 wardrobe, 1 chest of drawers, a bed’. The nurses’ rooms were also simple. A list of furniture shows each nurse had besides a bed a dressing table, towel rail, a chair or armchair, some had a locker or wardrobe, and linen baskets. Only one of the 102 rooms on the list had a carpet.

Other documents within HOSP/STAN/2/1/2 show a little of what living in the Nurses’ Home would have been like. A staff recreation fund was established some time in 1946, and an itemised list details ‘from Inauguration to 7th April 1947’ what was spent. This money came partly from the Sanatorium Committee, who gave £95, but money also came from member subscriptions and a raffle. The biggest purchases were on a dance – with £61 12s spent on a band; £8½ 1s 3d on food; 10s on domestic help, presumably for the tidying up afterwards; £3 13s 3d was spent on decorations; there must have been a prize-giving, as prizes cost £1 6s 4d; and printing stationary and postage for the invitations cost £2 19s 7½d. It would be interesting to know when this took place; perhaps it was the domestic and nursing staff Christmas dances.

Other entertainment came from three wireless radios and a second-hand sewing machine. This must have been for the staff to make their own clothes, as we know from a linen list also found in HOSP/STAN/2/1/2 that their uniforms were made within the sanatorium by in-house seamstresses. Books for a staff library were included on the list, mostly technical nursing textbooks but £5 was spent on fiction. Tennis balls, playing cards, a dartboard and darts and give an impression of how the nurses socialised in their free time. Practical needs were not forgotten, a hair dryer and electric iron also made the list, and spiritual needs thought of in the re-wiring for the chapel to keep it in use. A list of furniture from this time also shows the nurses’ sitting room had a grand piano and a pianola. The furniture list for the nurses’ sitting room shows there were three settees, leather and occasional arm chairs, a moquette tub chair, three tables, a writing table, sideboard, bookcase and a mirror pinched from the matron’s sitting room at Hexham Hydro. The nurses’ dining room contained 12 oak tables and 31 chairs. There were also individual sitting rooms for the higher ranks such as staff nurses, sisters and the matron. The domestic staff had their own dining and sitting rooms, and the teaching staff also had their own dining room. The photographs below are from a 1936 brochure for the sanatorium, and judging by these descriptions it seems there wasn’t a great deal of change in 10 years!

A 1946 list from HOSP/STAN/2/1/2 of the distribution of staff and patients shows there was an assistant matron, home sister, night sister, 2 ward sisters, two trained part-time nurses, 5 assistant nurses and 17 probationer nurses. Another list shows how the numbers fluctuated throughout the year. In the January of that year the 34 nurses were split fairly evenly between resident and non-resident, but by December only 4 lived outside of the sanatorium.

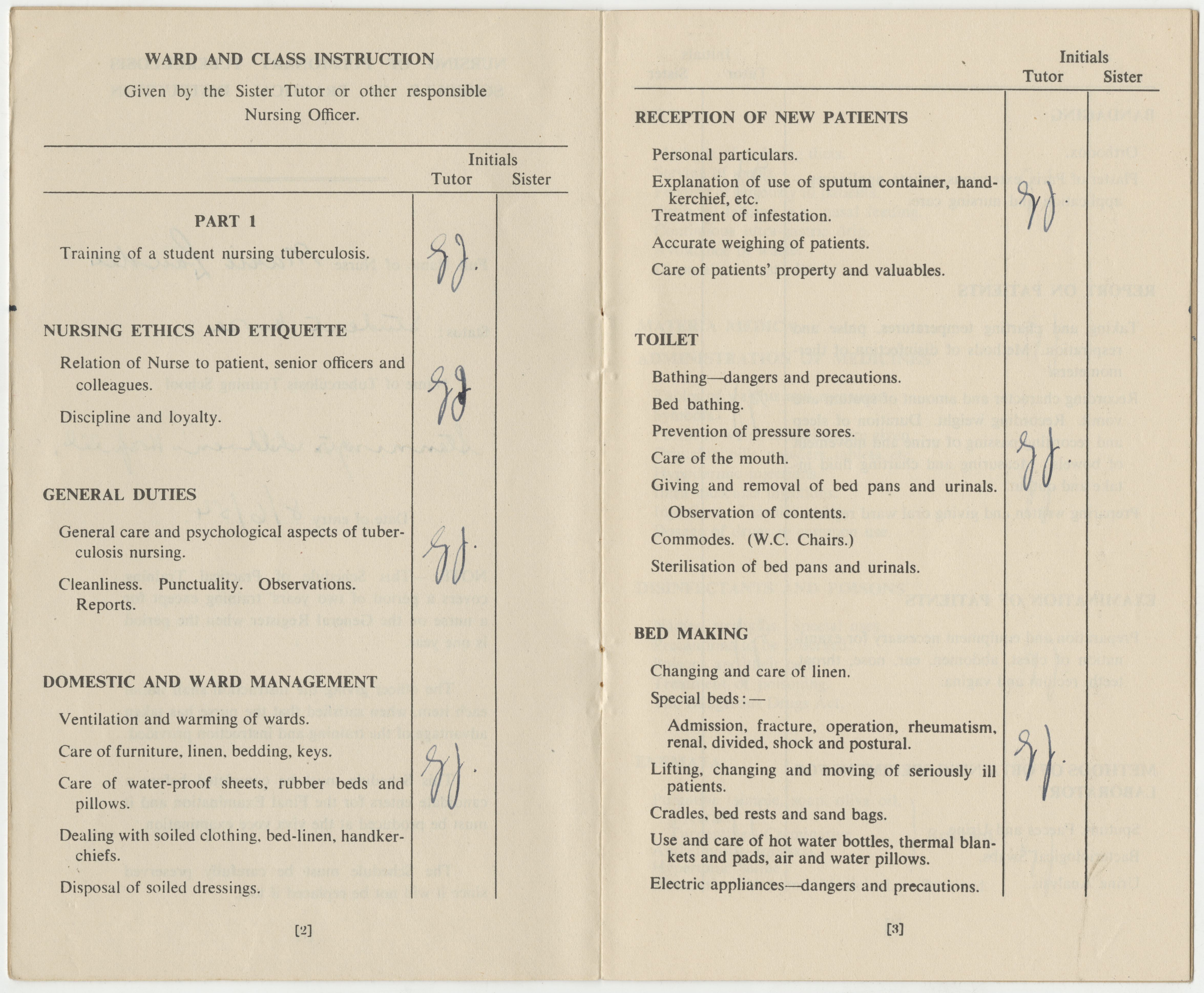

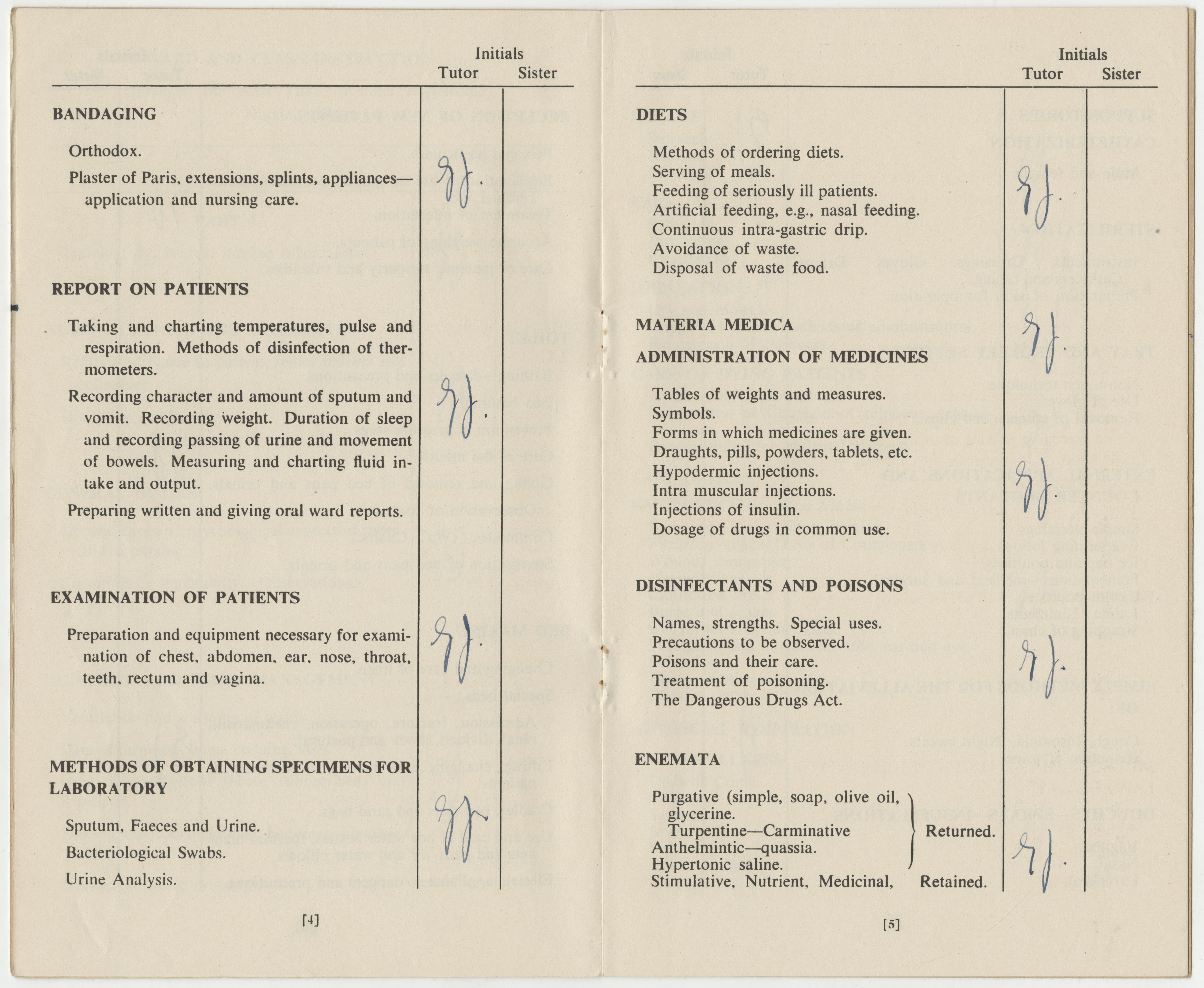

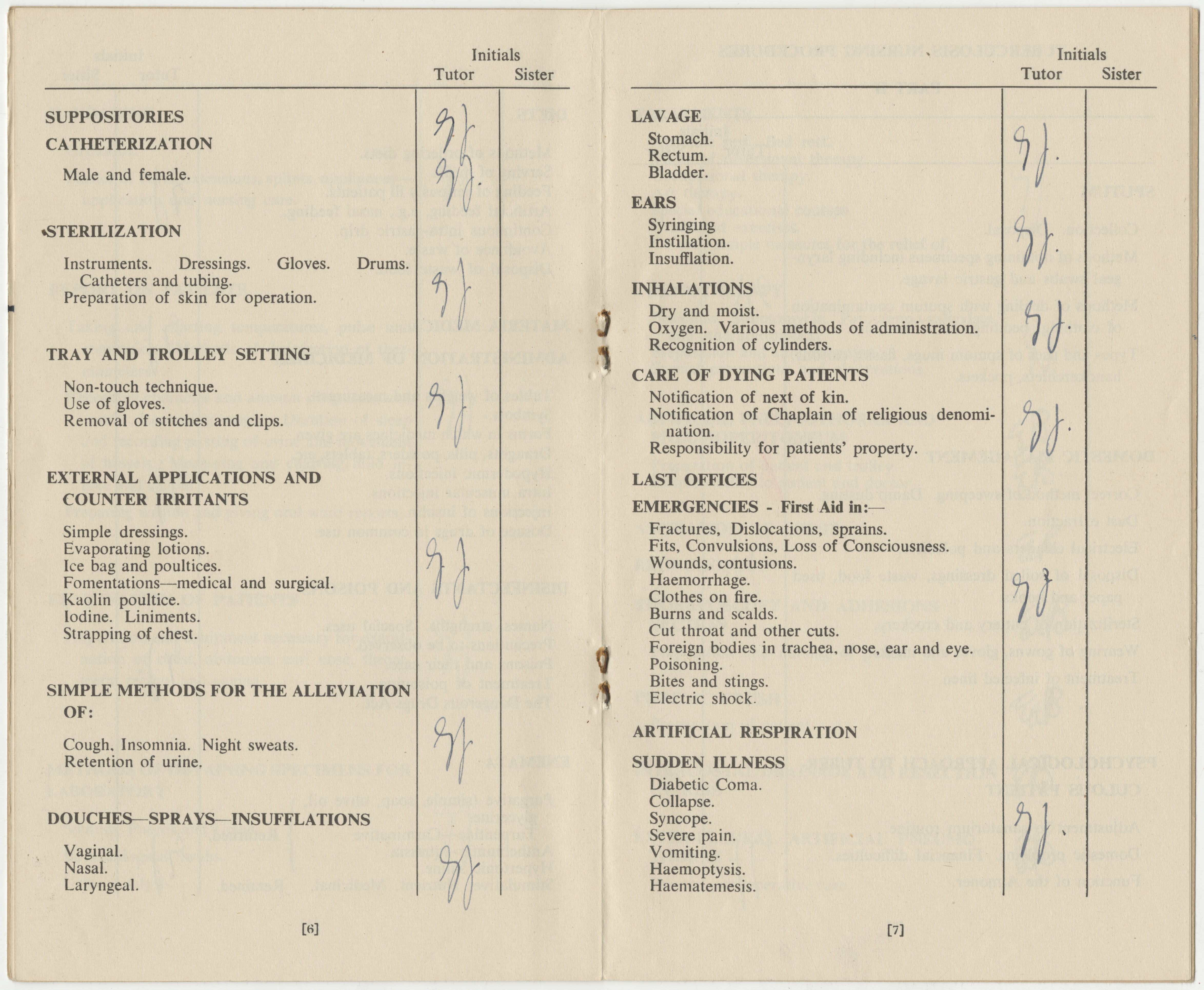

We know that the number of patients and nurses had dwindled during the war years, but they were boosted after the war, particularly by student or ‘probationer’ nurses. The 1947 annual report (HOSP/STAN/2/1/3) discusses the future use of the hospital for training junior nurses, the ‘probationer’ nurses mentioned earlier. They had lectures given on site by the doctors (such as Doctor Stobbs) and other medical staff, and took an exam. This can be seen from the Nurse’s Schedule of Practical Instruction (NRO 10352/27), a book where their competency in each area was shown by a signature of one of the lecturing medical staff. The book takes the student from basic cleanliness, punctuality and organisation up to taking sputum samples, bronchoscopy and treating patients with chemotherapy such as Streptomycin. Below are some of the pages from the book. The nurse who owned the book completed her training, and each section is signed off.

If you would like to find out more about the nurses at Stannington Sanatorium please have a look at our online exhibition, which features the stories of Matron Isabella Campbell and Florence Parsons, and memories from other nurses.

If you would like to find out more about the nurses at Stannington Sanatorium please have a look at our online exhibition, which features the stories of Matron Isabella Campbell and Florence Parsons, and memories from other nurses.